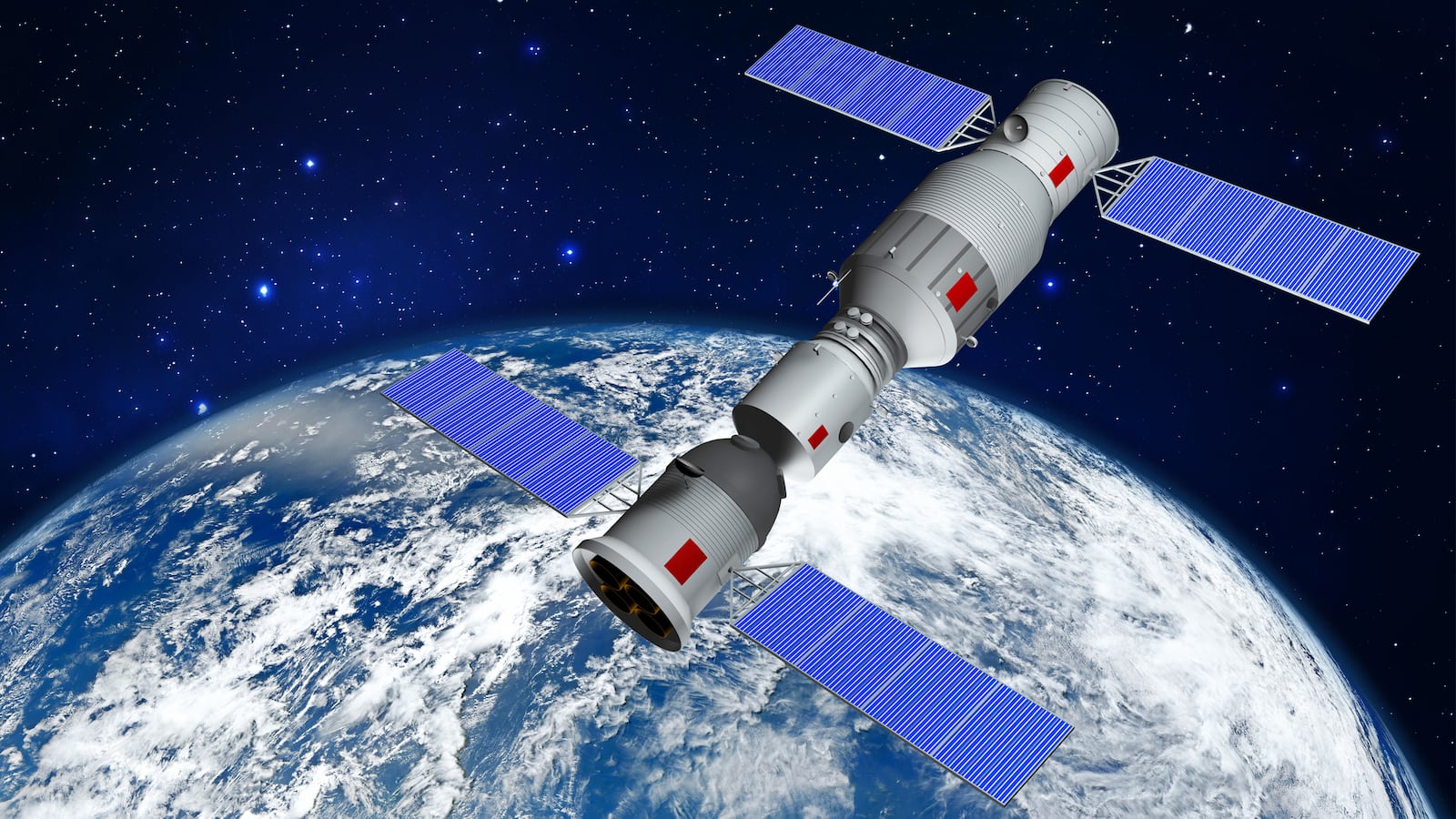

China’s very first space station, abandoned two years ago, is falling toward Earth and should enter the atmosphere on April 1.

But don’t worry. The 35-foot-long, 9-ton Tiangong-1 station will almost certainly burn up before any part of it can strike Earth’s surface.

The real threat to the rest of the world lies not in Tiangong-1’s flaming wreckage, but in the technological progress the station represents—and what comes next.

While the Trump administration considers cutting off funding for the International Space Station—currently the planet’s only operational space habitat—the Chinese government is steadily working on a new, larger orbital station that could eventually replace Tiangong-1.

If Trump gets his way and Chinese plans come to fruition, it’s possible that by the mid-2020s China will be the only country with an orbital station.

The China National Space Administration launched Tiangong-1 atop a Long March 2 rocket in September 2011. Chinese astronauts first visited the 11-foot-diameter station in June 2012.

Beijing officially decommissioned the station four years later amid reports of technical malfunctions. Tiangong-1’s orbit began slowly decaying, bringing it steadily closer to re-entering Earth’s atmosphere.

The Chinese station is hardly the first major spacecraft to come to a fiery, gravity-assisted end. The U.S. Skylab space station burned up in the atmosphere in 1979 after NASA lost control of it. Several Russian Cosmos and Progress spacecraft also tumbled uncontrolled back to Earth.

“China has [acted] no more or less responsibly than any other nation regarding the Tiangong-1, as many hundreds of spacecraft have re-entered Earth’s atmosphere, many of them much more dangerous,” Clay Moltz, a space expert at the Naval Postgraduate School in California, told The Daily Beast.

In December, the Chinese space agency warned the United Nations of Tiangong-1’s impending burn-up, NASA spokesperson Cheryl Warner noted. The U.S. Air Force’s Joint Space Operations Center at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California has tracked Tiangong-1 since its launch, and even publishes the station’s location on a public website.

In late March the Chinese space agency announced, via state media, that Tiangong-1 “should be fully burnt as it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere.”

Contrast Tiangong-1’s likely clean re-entry to the messy destruction of Russia’s Phobos-Grunt Mars probe. Phobos-Grunt malfunctioned shortly after launch in November 2011 and, two months later, plunged uncontrolled into the the Pacific Ocean west of Chile with 10 tons of toxic hydrazine aboard.

“It appears that China has managed Tiangong-1 as well as anything can be managed in the difficult and distant environment of space,” Joan Johnson-Freese, a space expert at the Naval War College in Rhode Island, told The Daily Beast.

“China has been increasingly transparent about its human spaceflight program—which Tiangong is part of—because they very much want the most often positive publicity that comes with space achievements,” Johnson-Freese added.

Beijing could score a PR coup in the mid-2020s, when Tiangong-2—the larger, potentially longer-lasting successor to Tiangong-1—should finally become operational. The China National Space Administration launched the first components of Tiangong-2 in September 2016.

In January, the Chinese space agency selected the first astronauts for Tiangong-2’s future crew. Beijing expects the station to be ready for human occupants in 2022, assuming engineers can solve technical problems with the station’s life-support systems and with the powerful Long March 5 rocket that’s slated to boost the rest of Tiangong-2 into orbit.

While China slowly assembles its next space station, the United States is considering disassembling its own station. The International Space Station, which NASA and partner space agencies completed in 1998, will need significant upgrades in order to remain safe beyond the mid-2020s.

The Trump administration has considered cutting off U.S. funding for the International Space Station in 2024. In that case, it’s likely that only private funding would preserve the station.

“The decision to end direct federal support for the ISS in 2025 does not imply that the platform itself will be deorbited at that time—it is possible that industry could continue to operate certain elements or capabilities of the ISS as part of a future commercial platform,” states a NASA planning document obtained by The Washington Post.

But the U.S. space industry isn’t particularly interested in covering the station’s $4 billion annual operating cost. Mark Mulqueen, Boeing’s space station program manager, told The Washington Post that the administration’s plan is a “mistake” that could “have disastrous consequences for American leadership in space.”

If Washington cuts the International Space Station’s funding and no private company takes over the station’s operation, the ISS could soon meet the same explosive fate that awaits Tiangong-1. And that could leave Tiangong-2 as humanity’s only off-world habitat, with China as its sole owner.

A Chinese monopoly on space stations would be the result of Beijing’s patient, unwavering approach to space exploration—an approach that, yes, occasionally results in an old, abandoned station dramatically burning up in the atmosphere.

American space programs tend to fluctuate wildly with successive presidential administrations. The Chinese, by contrast, “are playing the tortoise to the U.S. hare,” Johnson-Freese said. “You know who ultimately won that race.”