Fermajdayi Detention Center, Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Regional Governorate, Iraq—The young man in the black tracksuit was 21 years old. His hair was dark, short-cropped and unwashed; his fingers were dirty but not bruised. There were no torture marks on his emaciated face. He looked dazed as he dragged himself from the cell in which the intelligence branch of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) had held him in solitary confinement for more than a year. He sat on a chair and stared down at the patterned floor. His hands, bound in shiny, chrome handcuffs, rested on his lap. Thus began our interview with Ali Qahtan Abdulwahab—an Iraqi, an Arab, a Sunni Muslim and a former warrior and executioner of the Islamic State.

Ali, the eldest of two boys and five girls by a laborer father, attended school in the hamlet of Ain Saran, near Mosul. The United States armed forces invaded Iraq in March 2003. “I was eight years old, and I remember it as a dream.” Five years later, a friend from Mosul convinced him to resist the American occupation. “I joined al Qaida.” This began a period of instruction in the use of AK-47 assault rifles and PKC machine guns. In 2010, he was selected for a special assignment. “We kidnapped a person, a policeman from Hawija.” They spirited the policeman from Hawija, a Sunni town near Kirkuk, to their camp in nearby Tel Eid. His unit’s emir, or prince, Mazn Mahmoud Abdulqadir, murdered the policeman with a gunshot to the head for “training” purposes. The following year, Ali carried out orders to kidnap three more policemen from Hawija. “I executed one, and the emir killed the other two. Pistol shots to the head. The jihadi mentality was a motivation for me. It never bothered me.”

After most U.S. troops withdrew from Iraq at the end of 2011, Ali said, “We kept a low profile.” He returned to school and worked part-time in construction. In 2013, al Qaida in Iraq (AQI) re-emerged as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Eighteen-year-old Ali joined. He did not tell his family. “In 2014, I pledged allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.” Having conquered most of the Iraq–Syria borderlands and threatening to expand his caliphate to the entire world, al-Baghdadi was at the peak of his ascendancy. ISIS sent Ali south to Baiji, where it was pumping Iraqi oil to finance its operations. He fought against the Shias of the Popular Mobilization Units or Hashd al-Shaabi. The Islamic State’s security department recalled him to Hawija before the Hashd al-Shaabi, along with the Iraqi army, expelled ISIS from Baiji in late 2015. In Hawija, he said, “We took a training course in how to slaughter and cut heads with a knife. We were a group of eight. They showed us videos.” He worked for ISIS intelligence. “I was collecting information on people smoking cigarettes, not shaving, or wearing the wrong clothes. I reported them. I knew some of them. Three or four were my neighbors. They took them away. I never saw them again.”

While on checkpoint duty: “I remember that ten peshmerga were captured. They were in the Hawija jail. Later the Wali [governor] of Hawija, Abu Omar, gave the order to a Kurdish mullah, Mullah Shwan, to behead those ten.” Mullah Shwan took him to a camp where ISIS was holding the Kurds. “Mullah Shwan gave the order to slaughter five of them,” Ali said, in a matter-of-fact monotone. “I did the job and slaughtered five of them.” The ISIS method was to hold the men face down on the ground, pull back their heads, sever their throats and wrench off their heads. Did they plead for mercy? “They did not say one word.” I asked what he thought about cutting off the heads of defenseless human beings. Like a death camp functionary testifying at an Allied tribunal after World War II, he answered, “It was an order, and it was a normal thing for me.”

“Do you have nightmares?”

“No.”

After the beheadings, Ali went back to informing on his neighbors and manning checkpoints, until ISIS found another mission for him. “An order came in from Emir Ahmed Saleh, a sector leader in Hawija. He sent me and my family to Kirkuk.” Kirkuk, a mixed city of Kurds, Arabs, and Turkomans, was by then in Kurdish hands. Ali did not tell his family the reason for the move, thus risking their lives without their knowledge. He shaved his beard to pass as one of many displaced Arab Sunnis unable to live under the rule of the Islamic State and seeking refuge with the Kurds. The emir ordered him to contact eight fellow ISIS undercover agents. “The plan was to do a vehicle explosion in Kirkuk.” He and his family settled into a camp for displaced people. A month later, PUK intelligence officers arrived at the camp. “They came specifically for me,” he said. The Kurds took him for interrogation. He supplied them with the names of his eight comrades, all of whom were arrested.

In this dirty war, interrogations are rarely humane. Kurdish intelligence officers confronting a man who had decapitated five of their unarmed comrades would not have been sympathetic. I asked, “Were you tortured?” For the first time, he looked me in the eye. “Yes.” How was he tortured? A Kurdish intelligence official interrupted, telling Ali not to answer and me not to ask. That information was “operational.” I changed the subject. “Do you have regrets?” Without emotion, he said, “I feel regret. I have had a lot of time to think. I think they are not on the right path. It’s wrong. What they are doing is wrong.”

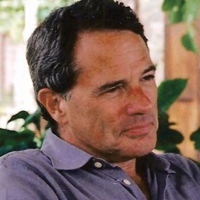

This is an extract from “One Picture, A Thousand Words” by Charles Glass and Don McCullin, published in Granta 140: State of Mind. Granta is the magazine of new writing. To subscribe, go to granta.com/subscriptions.