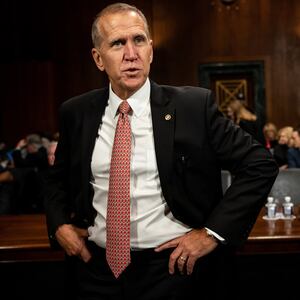

Sen. Thom Tillis’ (R-NC) campaign spokesman acknowledged on Friday that he had copied large portions of a general election strategy memo from a similar document he had put together while working on Ed Gillespie’s 2017 bid to be governor of Virginia.

The memo, which was released this past March, laid out an optimistic case for Tillis’ chances of re-election in North Carolina following former state senator Cal Cunningham’s emergence from the Democratic primary. But many of the arguments used the same language as a June 2017 memo that Gillespie’s campaign sent out after now-Gov. Ralph Northam emerged from his primary campaign.

“As we begin the general election phase of the 2017 race, the Gillespie campaign is in a very strong position both internally in terms of organization and resources, and externally in terms of the candidates’ positions on the pressing issues facing the Commonwealth,” read the Gillespie memo, which went on to tout the campaign’s “robust ground game” and slam their supposedly far-left opponent.

“As we begin the general election phase of the 2020 North Carolina Senate race, the Tillis campaign is in a very strong position both internally in terms of organization and resources, and externally in terms of the candidates’ positions on the issues that matter to the people of North Carolina,” the Tillis memo read, which went on to tout the campaign’s “robust ground game” and slam their supposedly far-left opponent.

That’s just one part where the memos mirrored each other. Tillis’ campaign memo also features multiple sections that are identical to Gillespie’s, right down to the same turns of phrase and political cliches. According to their respective memos, both candidates “begin the general election right where they want to be… firmly in the center-right” and boast “an army of supporters who are ready to win in November and who are ready to work to make that happen.” And for each candidate’s Democratic opponents, their “primary victory was a costly one… both financially and politically.”

In a statement to The Daily Beast, Tillis spokesman Andrew Romeo acknowledged that he had crafted both memos and said doing so was “a mistake.”

“I worked on the Gillespie campaign,” Romeo said. “The race narratives for both campaigns were similar. In my experience, campaign memos tend to follow a similar structure and format. But that doesn’t excuse how closely I crafted the Tillis memo to the Gillespie one. It’s my mistake and mine alone, as no one else from the Tillis campaign knew about the Gillespie memo. It won’t happen again, and I’ll accept any disciplinary action from the campaign.”

The political environments facing Tillis and Gillespie differ in important ways. By 2017, Virginia had become a state that favored Democratic candidates, while the North Carolina of 2020 is a fiercely-fought battleground where Republicans have long dominated. Tillis has the advantage of incumbency over an opponent who currently does not hold office, while Gillespie was running against a sitting lieutenant governor.

Nevertheless, the use of the Gillespie memo as a boilerplate for the Tillis campaign’s own election outlook invites some unfavorable analogies. A longtime GOP operative, Gillespie ended up being caught between an increasingly liberal electorate and an increasingly Trump-loving base. He ultimately chose to focus on the latter, closing the campaign by warning about MS-13 gangs taking over Virginia. That embrace of Trumpism resulted in a general election loss of nine points—the worst showing for a Republican candidate for governor in Virginia in 30 years.

A similar political landscape now faces Tillis: Democrats are more optimistic about their chances in North Carolina, and the senator’s bid for a second term is likely to be one of the hardest-fought Senate races in the country this November. That, plus the fact that both Democratic candidates faced more liberal primary challengers, could have made the grafting of Gillespie’s campaign rationale onto Tillis’ seem sensible.

Both memos analyze their opponents in the same way, declaring that the Democratic primaries “turned the conventional wisdom… on its head.”

“Prior to the entrance of [progressive challenger] Tom Perriello into the race, it was widely assumed that the Republican Party would have the fierce, angry and extremely ideological primary, while [Northam] would simply spend his time raising money and playing to the political middle,” reads Gillespie’s memo. “What a difference half a year makes.”

Likewise, the Tillis memo reads: “It was widely assumed that Senator Tillis would have the difficult primary that would pull him to the right, while Cal Cunningham would simply spend his time raising money and pandering to the political middle. What a difference six months makes.”

While the Democrats were “busy seeing who could get”—or “race”—”furthest to the left,” each GOP campaign memo theorizes, they were able to “unite” their own parties.

Memos like these are meant, primarily, for public consumption and don’t often provide honest reflections of the internal campaign mindset. In the case of Gillspie, the memo did not convey the actual realities of the race. The former top Bush aide would struggle in the general election due to his inability to unite his party. In the primary, he barely defeated his ultraconservative rival, Corey Stewart, who ultimately never endorsed him. Northam, meanwhile, was able to consolidate Democratic support after defeating Perriello, who promptly endorsed him.

Though Tillis managed to scare off a serious primary challenge from the right, he’s faced criticism after announcing he’d vote to block the president’s controversial move to use emergency funds to construct the border wall—a position Tillis later reversed under fire. Since then, North Carolina Republicans have questioned why Tillis hasn’t more vocally defended his colleague, Sen. Richard Burr, who is under federal investigation over his stock trading activity amid the coronavirus outbreak.

It was, in the end, Gillespie’s tortured relationship with the GOP base that ended up persuading him to move, over time, to the extremes of his party—something he acknowledged after he lost. In a postmortem interview with David Axelrod, the Obama strategist, he said his campaign consultants were telling him to run the MS-13 ads rather than ads on what he wanted to focus on: supposedly those touting criminal justice reform.

“Clearly, [the MS-13 ads] didn’t work. Did it create a backlash?” he asked. “I don’t think so. But I don’t know.”