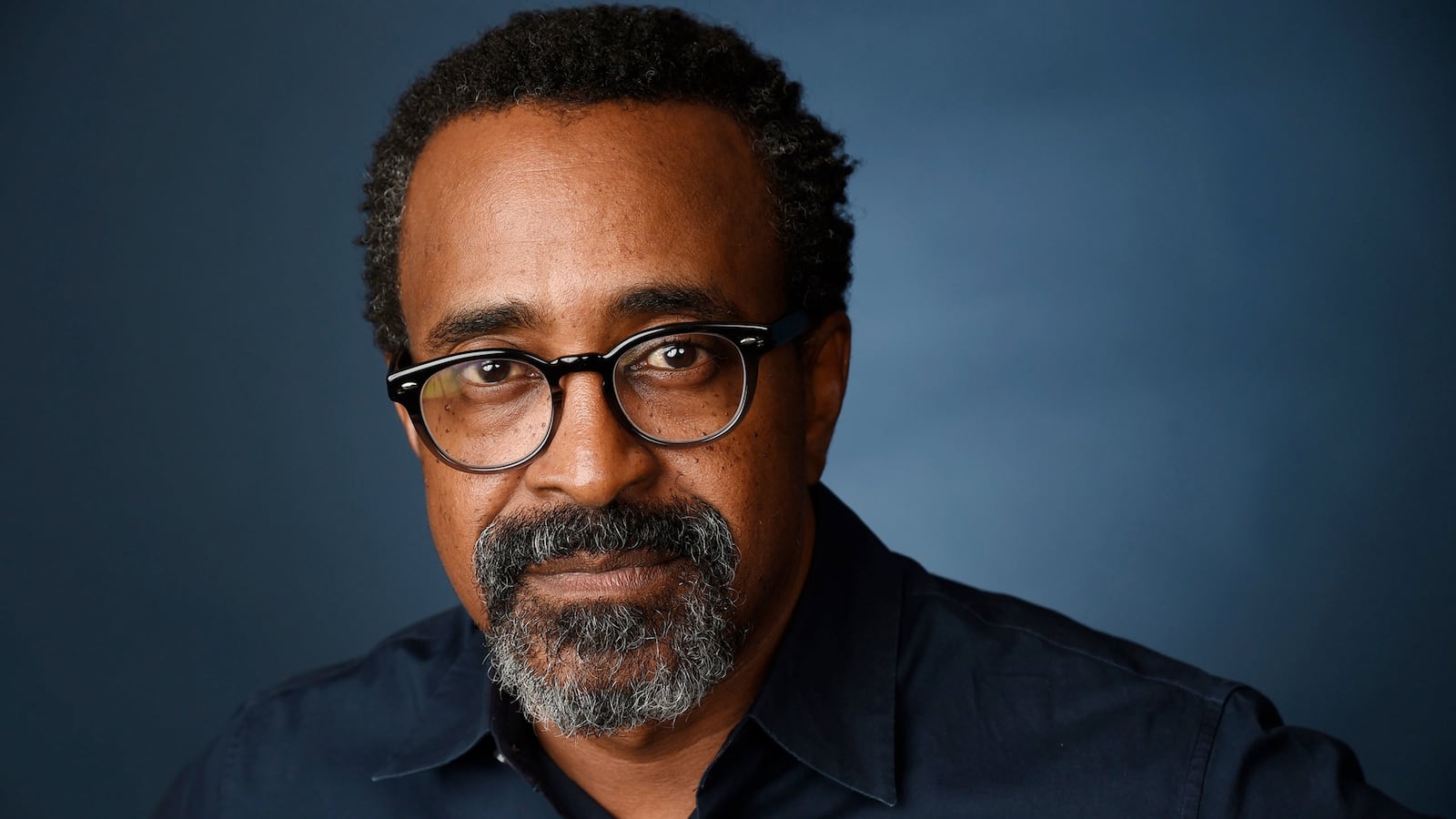

ATLANTA, Georgia—It’s hard to pick a favorite Tim Meadows performance. For some, it’s as the exasperated high school principal in Mean Girls, a carpal tunnel-afflicted man at the end of his rope; others may favor his scene-stealing turn as a drug-fueled drummer in Walk Hard who repeatedly tries to warn his lead singer off partaking. On The Office, he had a memorable sing-along date with Michael Scott (and margaritas) at Chili’s, and The Colbert Report saw him feign sweet, sweet ignorance as right-wing pundit P.K. Winsome, who felt he was fulfilling MLK’s dream by hawking Obama merch.

Most know him from his decade-long tenure on the sketch-comedy show Saturday Night Live—the third-longest ever—where he played everyone from O.J. to “The Ladies’ Man,” and served as a key writer.

These days, the 58-year-old funnyman features as Principal Glascott on the ABC sitcom Schooled, a ’90s-set spin-off of the network’s hit The Goldbergs. He’s a bit more dedicated than his Mean Girls principal but just as unlucky in love.

I had the pleasure of sitting down with Meadows at SCAD’s aTVfest to discuss his transition to sitcom star, time on SNL, and more.

What is it about you that makes you so good at playing these school administrators—in Mean Girls and now Schooled?

I’ve been asked why I get these sorts of parts. I guess I’m older than I used to be, and Mean Girls does have something to do with the perception of me as a [school] administrator, but this thing came about because I was asked to do the part on The Goldbergs, and when I read it originally it seemed so different from the teacher in Mean Girls. I played that as if it was gonna be his last year teaching—he was over it and so done—but this guy was more present, wasn’t a happy person, and didn’t have much of a home life. And now, on this show, he’s in charge and you find out how much he actually loves teaching. There was a growth period between The Goldbergs and Schooled where he started caring about his job a lot more.

How do you find acting on a comedy sitcom different from, say, doing sketch-comedy work for Saturday Night Live?

With network sitcoms, there’s a certain comedic rhythm that’s inherent to them—it’s punchline, setup, conflict and resolution. As far as acting, the difference is that sketch acting is more commenting on something—you’re not really pretending to be real—whereas this is a heightened version of pretending to be real. So these are real characters, but they say and do things that a regular person certainly wouldn’t do.

And I imagine there’s more wiggle room as far as improv goes.

Even with sketch performance there’s a script you stick to, and there’s a little room, depending on who you’re working for, where you can deviate from that script. We would do it on SNL on sketches we wrote personally, so you didn’t feel like you were ruining some other writer’s gig, or if you were working with people that you liked to have fun with on camera. Working with Will Ferrell, Molly Shannon or Jimmy Fallon, for me, it was always really fun to see if I could make them laugh during the scene.

During an MTV sketch I got Jimmy to break once, because he had one line in this sketch that was supposed to be a punchline, and I told him during rehearsal, “It’s not going to get a laugh!” and he was just cracking up about it, insisting it would. I told him that for three days, and then we got to the dress rehearsal and it got nothing and he just looked at me, dropped his head, laughed, and started walking off. [Laughs]

Tim Meadows and the cast of 'Schooled'

Craig Sjodin/ABCThere seemed to be more chemistry—or maybe it’s camaraderie—in your SNL heyday than we see today.

During that period, a lot of us had chemistry because those guys—Rock, Sandler, Spade, Schneider—knew each other from stand-up and they had been friends for a while, and Mike Myers, Farley and myself knew each other from Chicago improv. There was a camaraderie, and then once we all got to know each other after two or three seasons, we hung out with each other all the time outside of the shows and really did become best friends—and we’re still friends now. That’s how it was with that group of guys, because we came in together. And then with the second wave, Norm Macdonald, Spade, Molly, Ana Gasteyer, Cheri Oteri, Will, it was a little bit different because in the beginning I didn’t know any of those guys. I knew David Koechner, Tina Fey, Rachel Dratch, Horatio Sanz, and Adam McKay. But then the same thing happened where once we started working together we did develop this chemistry together.

What do you think changed?

The only difference now, I think, is the people who go to SNL are more prepared for what SNL is and what they do there, whereas when we came to SNL, I had never shot a video short and put it online—because there was no internet. So when Sandberg and the Lonely Island guys came to SNL they were already pretty professional in what they were doing, and it’s the same for a lot of those people. Kenan is great—I love him, and he makes me laugh—and one of the reasons why he’s so good is because when he was 12 or 14 he had his own sketch-comedy show, so he’s been very aware of this whole thing. He learned how to play for the camera, play for the audience, and learned what this thing was all about. When I was 12 or 14, I was in junior high watching SNL at home and had no idea what it was all about.

I love your performance in Walk Hard.

“You don’t want no part of this!” [Laughs]

“And you never once paid for drugs.”

The whole drug thing was scripted but the only part I improvised was during the very last one, when we were in our Pet Sounds phase and the band was going to break up, and I said, “And you never once paid for drugs.” It was set up so that [Chris] Parnell would say what was wrong, [Matt] Besser would say what he hated, and then I’d say, “And you never once paid for drugs,” and then the camera goes back down again, Chris says another one, Besser says another once, and it comes to me, and I just thought in the moment it would be funny to say the same thing again, as if this was the only thing that pissed my character off. So we did it the first time, and when I improvised it in the close-ups I could hear [director] Jake Kasdan laughing off-camera. So I was like, OK, I’m going to be even more intense about how I say it the second time around. And those guys kept it in the movie. I was very proud of that moment.

I know you came up at Second City with Chris Farley but what about Steve Carell and Stephen Colbert?

We were all basically hired at the same time for touring companies, and I knew those guys from doing improv in Chicago too, but they came to the Mainstage of Second City after we left.

That must have your own personal Beatles-in-Hamburg, doing improv at Second City.

It taught me so much. That’s all you do: live, breathe, eat comedy. People have asked me how I got SNL, and there was a point when I was in Chicago at Second City on the Mainstage, and we did eight shows a week, and then on my day off—which was Sunday—I’d do another improv show at ImprovOlympic. I did that for maybe six weeks to two months, and it just so happened that SNL came while I was doing that, and the reason I got SNL was because I was hot. They came and watched the improv sets, and each time the producers and writers came, I was already on fire because I was doing it just all the time. So those days, that’s what it was—all your time is focused on your art. And I’ve never had that in my life other than Chicago.

There seems to be a troubling history of phenomenally talented black comedians getting shortchanged on SNL, like yourself, Chris Rock, even Eddie Murphy to a degree. Why do you think that is?

You know, I don’t really have an answer to that. I don’t think it was a thing that was on purpose, and that the producers or the network were like, “Let’s not put them on the show,” I just think that you had to compete with really talented writers and performers, and there’s only a certain number of slots on the show every week. When I first started, I was a “featured player,” so my sketch isn’t gonna get on before a Dana Carvey sketch because it’s his show and I’m just a new guy. But as you put more time into it, you start to get more consideration and people understand the value you have. For me, I started writing sketches for other people, because I wanted them to like me as a writer, and after that I could write sketches that had nothing to do with me being black or anything, and they took it seriously.

What were some of your favorites?

I enjoyed this commercial for “Jiffy Pop Airbags.” There was also this sketch called “Soap Opera Digest” with Alec Baldwin, about a soap opera actor who was dumb and didn’t know how to pronounce certain words—even though he played a doctor! And all the “Ladies’ Man” sketches. Oh, and I wrote this thing called “The Princess and the Homeboy” with Teri Hatcher—a Fresh Prince parody—and it was the first time that NBC let us shoot it during dress, because there was cursing in it, and then they aired it and bleeped out the curses. I was very proud of that moment. I used to do these sketches with Sandler called “Captain Jim and Pedro.” We did it maybe three times, and it was the most fun writing-and-performing experience I think I’ve had.