Within hours of ProPublica’s blockbuster report showing just how little America’s 25 wealthiest people pay in taxes, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig announced an investigation, which, of course, is what great journalism into a scandal is supposed to generate: a renewed commitment by senior government officials to fix an obvious scandal.

But Rettig wasn’t looking into how broken the tax system is in favor of the wealthy, but rather about who leaked the documents proving that to the press, stating that he intended to prosecute the whistleblower if the investigation found the records were distributed illegally. While the data leak does present security concerns for the IRS—an agency which has been much more successful at protecting the sensitive financial information of millions than banks or Silicon Valley—the bigger issue here is the significant failures of the IRS and our tax administration at large in ensuring the fair application of the tax code.

A commissioner who prioritizes the justness of the system would see the report as a prompt for self-reflection rather than immediately trying to redirect blame on a whistleblower who released information relevant to the public interest. That’s the latest reason we believe that Joe Biden should replace Rettig—who was appointed by Donald Trump to shield his personal tax returns—and install someone committed passionately to making tax collection functional again.

This isn’t the first time Commissioner Rettig has shown his allegiance to protecting the interests of the wealthy over the public interest. Prior to becoming commissioner, Rettig worked at a boutique Beverly Hills law firm for three decades, where he specialized in shielding wealthy taxpayers from IRS audits. In 2010, when the IRS announced the creation of a task force focused on auditing the very wealthy, Rettig publicly denounced the task force’s work as “audits from hell,” a particularly troubling pronouncement from someone now in charge of said audits.

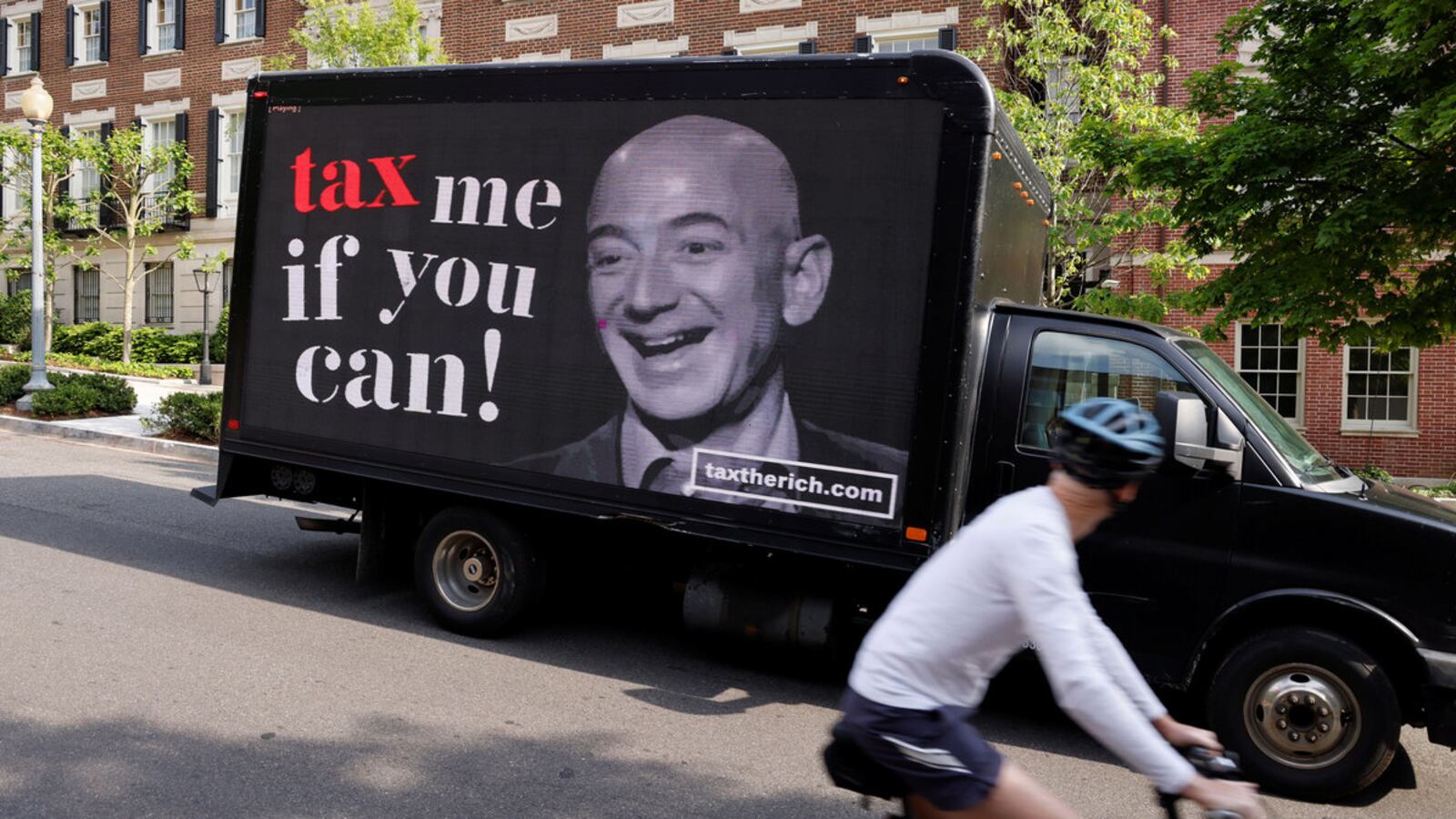

With the newly released ProPublica data, however, Rettig’s comment takes on a particularly absurd tone. We now know that in 2011, the year after the creation of the task force, Jeff Bezos reported so little in taxes that he was able to claim a $4,000 child tax credit. And Bezos wasn’t a unique case; Elon Musk, Michael Bloomberg, Carl Icahn, and George Soros all paid zero income tax in at least one year covered by the ProPublica report. Suddenly, Trump’s $750 tax bill in 2016 and 2017 no longer looks so paltry.

ProPublica characterized the billionaires’ low income tax payments as a result of tax avoidance, the legal usage of financial planning and loopholes to reduce tax liability. But there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of the deductions these billionaires took that allowed them to claim zero income and therefore pay zero income tax—a prospect which would more properly point to illegal tax evasion. The wealthy regularly use secretive and complicated business arrangements to shield income from IRS scrutiny while using other, harder-to-parse activities, like donations of property, to reduce their taxable income even further. According to a recent study on the tax gap, the top 1 percent of income earners on average do not report 20 percent of their incomes, particularly pass-through business income and wealth stored in offshore accounts.

But IRS energies in recent years have focused primarily on the lowest income earners, particularly claimants of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a tax program designed to assist poor workers, particularly those children. The program has long been besmirched as riddled with fraudulent claims, and the IRS has obligingly allocated its resources towards auditing EITC claimants, sometimes targeting honest, vulnerable taxpayers in the process. EITC overpayments make up only about 4 percent of the tax gap even when using the most aggressive estimates. On the other hand, unreported business income accounts for a full 27 percent, and this is likely an underestimate given IRS shortcomings with detecting pass-through income. Despite this, with significantly declining resources, the IRS has more quickly scaled down its audits on the wealthy and large corporations than its audits on poor EITC claimants, even though audits on the rich yield more revenue per audit hour than, unsurprisingly, inquisitions into the working poor.

ProPublica’s reporting confirms what many have suspected for a while: that our tax system and our tax administration are thoroughly and inequitably broken. ProPublica’s source remains unknown, and the outlet expressed some concerns that it could be a foreign government adversary, but with no signs of a hack, the most likely explanation currently points to an IRS employee concerned by the agency’s inability or unwillingness to properly oversee the fair application of the tax code.

With even aggregate tax data slow to be released, the tax filing data revealed is of crucial importance, shedding light on the precise ways the wealthiest shelter their wealth. And, though some of the billionaires whose tax information was disclosed decried the release as a criminal invasion of privacy, it’s unclear what harms come from the release. Indeed, as ProPublica noted in its defense of its reporting, numerous Nordic nations like Sweden, Norway, and Finland regularly make public the tax returns of all citizens with no significant deterioration of privacy.

Commissioner Rettig could have viewed this reporting as a wake-up call and a moment for introspection on how the agency he leads can do better, will do better. Instead, he immediately cast his gaze outward, expressing concern over the violation of billionaires’ right to privacy (which, in this case, means their right to evade scrutiny on their manipulation of the tax system) and declaring his intentions to prosecute. Rettig still has not commented on the substance of the ProPublica reports and what he intends to do to remedy such blatant tax injustice.

Rettig’s interests clearly lie with the wealthy and protecting their privacy over all else. The action that likely tipped the scales in Rettig’s favor when Trump needed to replace former IRS Commissioner John Koskinen was Rettig’s defense of Trump for not releasing his tax returns during the 2016 election. With Democrats intending to use their congressional authority to compel the release of said tax returns, Rettig was the perfect shield, one with both a professed support for Trump’s refusal and experience in fending off tax scrutiny.

President Biden should see Rettig for who he is: a Trump appointee installed to protect the interests of the wealthy, including but not limited to Trump himself, above all else. By immediately forefronting the tenuous and suspect privacy concerns of billionaires, Rettig’s response to the ProPublica reporting is just the latest display of his fundamental allegiance. If Biden is truly committed to reforming our tax system by finally making the wealthy pay their fair share, he will exercise his clear legal authority and replace Rettig at the helm of the IRS.