This story contains references to suicide. If you or someone you know is thinking of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or text TALK to the Crisis Text Line at 741741. Also: Trans Lifeline is at 1-877-565-8860.

The last time David Feldmann saw his daughter Haley alive, she surprised him by asking for a hug. He was up late watching some films, and Haley joined him. “We watched three movies together,” he recalled to The Daily Beast. “Then I realized it was about 2 in the morning. I said, ‘Oh I better go to bed.’ She was like, ‘Hold on, let me give you a hug.’ And she came over and gave me a big hug and told me, ‘Good night.’ That was it.”

David treasures the sensation of that hug. “It was weird, she was not a hugger,” he says.

Sitting next to him, holding her husband’s hand as she has done for the last two hours, Christina, Haley’s mom, says quietly, “She’d already made her mind up.”

Only in the last few weeks of her life had Haley started requesting hugs from her parents after a long time rebuffing them. They took heart from this. It seemed their beloved daughter was maybe opening herself up to them again.

“The memory I have is that she was so at peace that evening,” David continues. “Even though it definitely wasn’t normal for her to give someone a hug, she’d been wanting more lately. You just never knew when they’d be coming. I wasn’t caught off-guard when she did it, but it was different, and now it is absolutely the most special memory I will ever have.” He chokes up, and holds his wife’s hand tight.

The next morning one of her siblings found Haley’s body at the family’s home in Beach, North Dakota. Haley Gabriella Feldmann died by suicide, aged 18, on Nov. 12, six days shy of her 19th birthday. The obituary posted in her name went viral online, making clear her family’s fierce love for her, alongside their anger at the transphobia and ignorance which they hold, to a significant degree, accountable for how Haley was feeling.

Speaking to The Daily Beast, the Feldmanns condemn the anti-trans legislation and rhetoric of the Trump administration, and the raft of recent pieces of anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ legislation in Republican-controlled state legislatures. North Dakota’s legislature passed an anti-trans sports bill last April, which was vetoed by Gov. Doug Burgum. The governor did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

“She had grown weary of the knowledge of her reality, knowing this country and this world would never stop trying to force her to submit to its ignorance, and her family rages for her,” part of Haley’s obituary reads. “We would’ve burned the whole world down if we’d thought it would keep her safe, and our fury and outrage is eclipsed only by our grief. We struggle against the currents that try to carry us away from love, for those currents only take us further from her. And she is far enough, already.”

Four members of the Feldmann family talked to The Daily Beast from their home: Christina, David, and Haley’s siblings Alex and Sam (the latter stays mostly quiet). They are visibly devastated, and raw and exhausted with grief. They cry, they laugh, they remember tenderly, they comfort one another, and share a jumble of conflicting feelings familiar to the loved ones of those who take their own lives.

As Christina makes clearest of all, their anger is focused on the bigotry which, she says, diminishes not just trans people’s civil rights, but also seeks to undermine their mental health and quality of life. If Haley’s death is to have any meaning at all, for the Feldmanns it is to make people stand up actively for LGBTQ and trans people. “Don’t just say you support LGBTQ or trans people, and then act surprised that the politicians you are voting for do not support them,” says Christina.

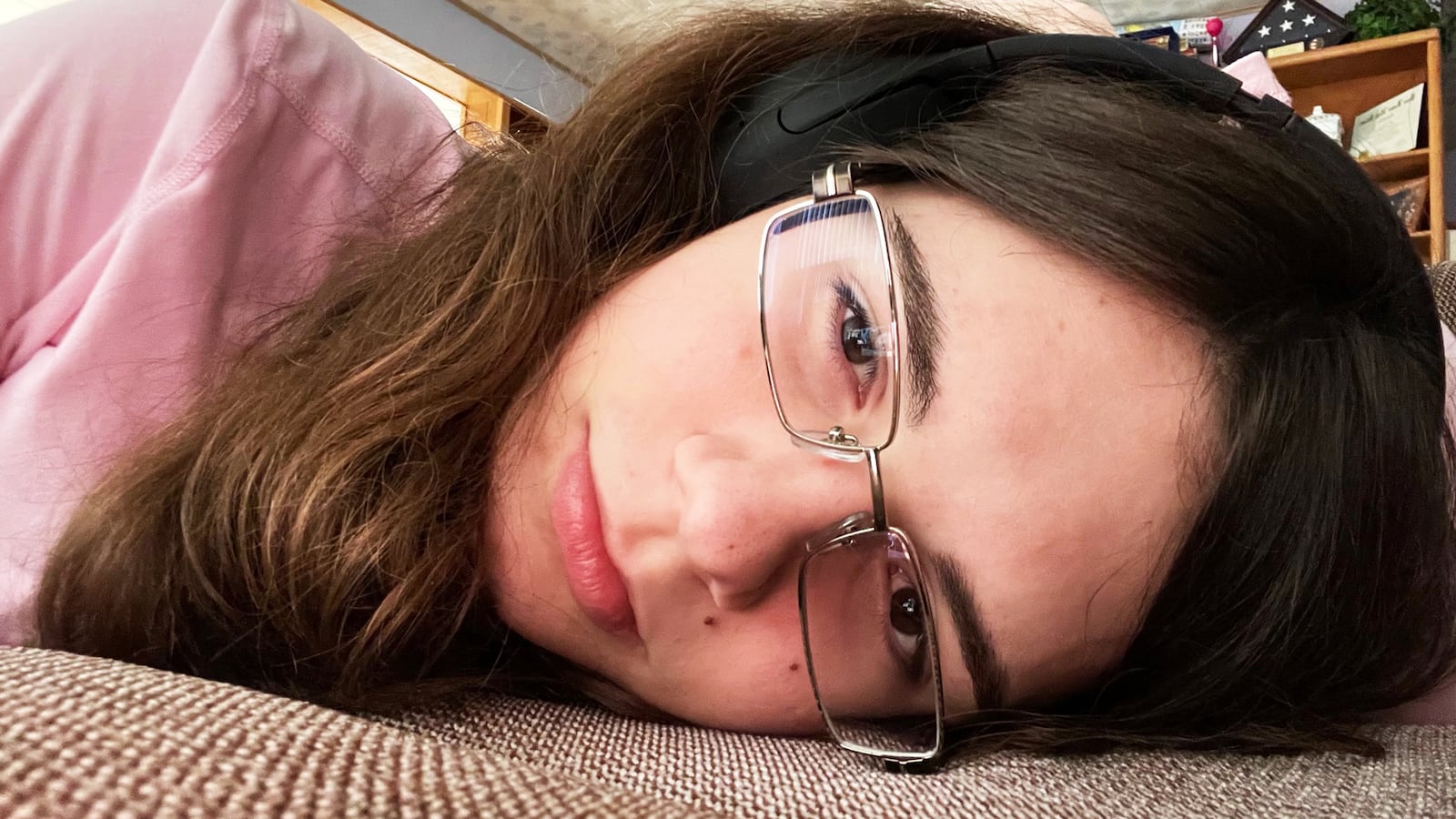

Haley Gabriella Feldmann

Courtesy of the Feldmann familyWhen asked how the family is doing, David says, “It depends on the moment. I am talking to several friends. People outside of this help.”

“It doesn’t feel real for me still,” says Christina. “I woke up yesterday, reminding myself to make Haley a doctor’s appointment, and… this is rough. All of us are struggling. It feels like I am stuck in a vicious loop. I’ve never known life without her. I work at a truck stop, and I got mashed potatoes and gravy from there the other day. She thought it was delicious. It was her favorite thing. She would always beg to me to bring some home. So the other day I picked some up, then remembered, and almost threw it out of the car.”

“Horribly. I’m doing horribly,” says Alex, who is non-binary. “I don’t know how to describe how I feel. She was my best friend. She was the most important person in my life. I considered her my twin. Sometimes I considered her older, even though I am older. I have absolutely no idea how to function without that part of me. Part of me is missing. Part of me has just gone. We grew up together. We did everything together. We once shared a bedroom and wanted to kill each other.” Alex laughs. “We’d always talk, be there for each other. We played video games together, went on walks late at night together.”

“I have started to realize how normal this is all starting to feel,” Alex says. “I’m getting used to it, and I don’t want to be used to it.”

Christina wrote the obituary for Haley, the hardest thing she has ever written, yet the words came easily. “She was my daughter.” David says it is “absolutely what we all wanted to say.”

“Haley never wanted anyone to know she was transgender,” Christina says. “She wanted to be able to pass and have no one question it. And thinking there was even the slightest possibility that she wouldn’t pass, the possibility someone might say something to her or be cruel to or harass her or criticize who or what she was—the fear of that happening was one of the things that drove her into near total isolation over the last few years. No one was cruel to her, but no one was given an opportunity to be cruel to her.

“Haley was very aware of the world. She understood politically what was happening in our country, and obviously she took it personally. We are not a poor family, but we have by no means a great deal of money. Affording surgery for her was not something we could do. If we’d been able to afford…” Christina’s voice breaks, and she begins to cry. “If our insurance would have covered it, it would have saved her life. She would still be here.”

Haley had deduced her procedures would cost around $180,000 in total, Christina says. “That was impossible for us, and just unfathomable for her. She was unwilling to allow anyone to portray her as anything but a woman, and that made it impossible for her to feel comfortable to get a job here. She was afraid of the way people would see her.”

“She was faced with having to fight for every single thing she wanted for herself,” says Christina, “having to fight everybody and everything at every turn, constantly being on her guard, waiting for someone to just be horrible to her, or living in her parents’ house for the rest of her life—and she didn’t want either of those things.” Christina cries again.

In a later email, Christina says the family had looked into gender affirmation surgery for Haley, “and as far as we could find, our insurance considered it elective. For some people it is. Not all transgender persons need or want to transition. For Haley it would have saved her life. But even if a doctor had said she had to have it in order to keep her alive, most health insurance would have declined to do so. It leaves only the financially well-off having the ability to save the lives of their loved ones. And for those that need it, it is not cosmetic, nor is it elective. It is life-saving.”

Christina added: “Her life and existence never should have been up for political debate. It should have been easy for everyone to agree that everyone has the right to personal autonomy. She should have been able to be comfortable in her day-to-day existence with the knowledge that society found anyone, and any laws, that shunned or rejected her existence to be distasteful and unacceptable.

“Instead, she felt the opposite of that to be true and it is shameful that our country continues to promote the stripping of hope from people simply because those people make them uncomfortable. If my daughter had received from society in general, the only things that mental health professionals insist can successfully ‘treat’ gender dysphoria—affirmation, validation—she might still be with us.”

Her parents say Haley was in therapy, and taking hormones. “But we live in the middle of nowhere,” says Christina. The nearest LGBTQ-affirming therapist was a two-hour drive away, and remote tele-therapy during the pandemic had not been helpful. Christina says Haley died on the morning of November 12th. Her brother Sam found her and called 911, but the EMTs were unable to save her.

“As far as we can see there was no one thing that happened immediately preceding this that decided it for her,” Christina says. “It was a combination of her social anxiety exacerbated by society’s ignorance of transgender persons and laws that promoted said ignorance and the unashamedly proud self-righteous justification for discrimination coming from people that have decided if something makes them uncomfortable, it shouldn’t be allowed.

“She was lonely, driven into isolation by society’s vocal, written, and legislated rejection, and that to hope for better without having to fight tooth and nail for every single scrap was unrealistic. She was exhausted from all of the hurt that this caused. So she opted out. Everything ‘Jane Doe’ said in her message on the memorial page [who outlined a traumatic personal experience] would have been validated and agreed on by Haley. She could’ve used most of it as a suicide note.”

More than once, Christina says, “I have so much anger in me,” as she contemplates this confining and imperiling landscape of bigotry. “It’s like I’ve got this scream trapped inside of me, and screaming’s not going to be enough. I’m angry that people, because of their own personal comfort, set out to destroy trans people. You don’t get to claim ignorance when you empower the people who are going to trample on my children’s civil liberties. You don’t get to be after the fact, ‘Oh my gosh, I didn’t know they were going to do that.’ That’s what they said they were going to do.”

‘I just wanted to be there for her more than anything’

Haley had a lot of confidence when she was younger, says Christina, always with friends, confident, funny, and laid back—except, she laughs, when her daughter was playing any kind of strategy game, “and then she got really intense. She meant business.”

David says Haley began to withdraw from the age of 12, dropping out of school in seventh grade. They tried home-schooling, but it didn’t work. “She just isolated herself in her room until school was over and then [would] disappear to a friend’s house,” says David. “I hate thinking about those years. I was always the one left home trying to get her ready for school.”

Christina says Haley would ask her parents about events in the world, “having conversations for hours.” She taught herself, and was particularly knowledgeable about history and geography. She loved Apple technology so much she could have been a salesperson for the brand, laughs David. “And everything Tesla, except for Elon Musk. When I saw the Starlink satellites in the night sky, she was the first person I called.” Christina laughs, recalling watching a documentary about Stonehenge, and Haley appearing to say, ‘Hey mom, if you need any help understanding that, I just got done watching it. It’s really fascinating.”

David, Christina, and Alex all agree that, had she lived, Haley would have positively changed the world. David laughs that he always expected her to invent a time machine, and was “annoyed that that wasn’t her thing.” Online, one of her favorite games was Nation States, which she played for years. Her family recalls her running her own country. Just before her death, she revealed she had conquered the game; the only thing she had left to do was dissolve the senate. “But she wasn’t focused on being the emperor,” says David. “She was trying to make civilization better for people. And, within 15 years, I believe she would have made an impact in the real world. That is what the world has lost.”

Christina recalls her as a formidable player of strategy games like Risk, Command and Conquer, and Stellaris, and how she “devoured” information about any subject to master it. There was also “an outpouring of love” from the online Discord community, where Haley had many friends, says Alex. She had also spent years literally creating her own world, with maps and its own language and political system. She did not leave a suicide note, her family says, but she did leave the code to gain access to her phone.

“We weren’t allowed to take pictures of her,” says Christina. “She hated her face. I thought she was beautiful. But on her phone she had pictures of herself, which we found recently.” The family doesn’t know if Haley left the access code for them so they would be able to have access to her pictures after her death, knowing they would cherish that. They like to think she maybe did.

Haley first came out to Alex at the beginning of 2019, and then to the rest of the family a year later. “I just wanted to be there for her more than anything, I wanted to make sure she knew I loved her unconditionally,” Alex says. “When she started coming out to people I was so excited, her number-one fan. She told me how much that meant to her. When she told you guys (their parents), she decided that her happiness and comfort with her own body mattered more than anything.”

“In that moment I wanted to be there for her more than anything,” says Christina. “I could tell whatever she wanted to talk about was weighing on her. I know I wasn’t exactly surprised, but I hadn’t been expecting it. It helped make our child make more sense to us. She was finally starting to let us know her again as who she was, and not whoever it was she thought she had to be. It was a privilege to be trusted with that. I am a cis het woman. I’m white, I’m an army brat. I’m from the south. The most discrimination I’ve ever experienced is as a woman. And that is nothing compared to what some other people experience—and certainly not what my children have experienced.”

David and Christina were accepting. Alex’s coming out as non-binary had preceded hers.

Alex’s declaration had also unlocked something for their father. “These are all thoughts I have struggled with all my life,” David says. “This has never been anything new to me, except during my growing up and upbringing you couldn’t talk about it. It was stuffed down inside. After Alex came out, that changed my whole perspective. I grew up in this (local) community all my life. I probably would have gone full trans woman. That’s absolutely where my mindset was during puberty, but it wasn’t OK back then. It wasn’t a shock to me when Alex or Haley came out, it was ‘What could I have done differently? What can I do now do differently? How can I support them better?’”

Christina and David have had a “lot of conversations” about whether he intends to transition. “All options are open, probably more so than they have ever been,” says David. “I think it would be a lot harder now than in my teens.” But he has read testimonies of people transitioning at ages older than his, and sharing his own struggles with his children has helped him and them understand each other. He and Christina have been together for over 20 years, and intend to stay together—their closeness is clear. Alex says their father talking to them about his experience had helped them be closer. “It has been very weird to realize how much my journey helped you and Haley,” they tell him.

“We always said you were the bravest of us,” Christina says to Alex. “When Alex initially came out, I didn’t know anything about being transgender or non-binary. It started me on a journey to understand all I could about it.”

‘Stop treating people’s existence and worthiness as debatable’

Alex, their parents recall, came out prior to the Trump presidency, “when life looked as if might be going in the right direction.” Christina had gone to Alex’s school to ensure the staff knew that trans and gender non-conforming students were protected by Title IX, the federal law that protects students from sex discrimination. She told the principal that Alex deserved, and was legally entitled, to respect. Alex had faced transphobic comments from a teacher, and Christina insisted the principal should not have had an issue with using Alex’s chosen name and correct pronouns, especially as staff and students used nicknames.

When the Trump administration rescinded Title IX protections, Christina said she was “terrified not for myself or my kids, but for other families.”

“Without Title IX I would have had nothing,” says Christina. “When they took that away, I thought, ‘How are parents supposed to ensure children are safe if the school insists on not being respectful to the children?’ An adult would not stand being named anything other than their chosen name, but somehow it’s OK to treat children like that? Why does it take federal protections to insist on something so simple?” (The Biden administration reinstated Title IX protections for trans students last June.)

The Trump administration’s animus towards LGBTQ people, and trans people in particular, had affected Haley, Christina says.

“To see so many people go out and vote for this person again last November told her something very disheartening. If people say they are allies, then go and vote for someone whose party interferes with other people’s civil liberties, you’ve obviously decided that people like Haley’s humanity is less important than your financial wellbeing. But your financial wellbeing should never come before another person’s life. Ever.

“Our daughter was a person, she was a beautiful, wonderful, loving, kind, intelligent person, and she would have been shunned by people simply for not conforming to their idea of who she should be. That’s bullshit, and it’s bullshit to do that to people. This should not be about your religious or political views. It’s about being a decent human being, and not letting other people trample on people who are not hurting anybody. People who vote for politicians who vote for anti-trans legislation are telling me my child was not worthy of decency.”

Does Christina hold anti-trans legislators in any way responsible for Haley taking her own life?

“To an extent yes. You can’t acknowledge and foster discriminatory ideas like that—leading to other people feeling empowered to be cruel because the state legislature said so—without bearing some responsibility for the cruelty. Your priorities should not be getting re-elected or ensuring future employment after your term, and certainly not maintaining your financial status. Stop treating people’s existence and worthiness as debatable, stop pretending like discrimination isn’t a real thing usually directed at innocent people for shallow reasons. Stop being shallow. Do your job and be better, or get out of the way so true patriots of American ideals can get the work done.”

Trump’s presidency felt like “being under attack for four years,” and Biden’s election brought “a huge sense of relief,” says Christina, but then Haley took the raft of anti-LGBTQ and anti-trans legislation in Republican-controlled states like North Dakota “as a sign of what she could expect in the world.”

Christina says she was raised as a Roman Catholic conservative Republican, believing “Ronald Reagan was the greatest president ever.” She began questioning this in her late twenties, and now it infuriates her “that Republicans say LGBTQ people want special rights when they just want access to the same rights as everyone else. You shouldn’t have to the Supreme Court for the right to marry or not get fired from your job because of who you are, and people should not be able to claim ‘religious freedom’ to discriminate against you. There need to be laws in place to protect LGBTQ people.”

Today, Christina believes in God, “but I don’t believe what they teach in church. I think the modern-day Christian concept of God is a load of crap. How can those people say my daughter was going against God? I don’t think God has anything to do with the physical body. My children were made inside me, my body, but Haley’s soul, her spirit—I believe that was a creation of God.”

Yana Calou, director of advocacy at Trans Lifeline, told the Daily Beast that Haley was far from alone in being affected by the presence of anti-trans bills, and the nature and tone of the debate around them.

“A big part of the danger created by these bills is that they create an inescapable public debate—even in states where they aren’t proposed or don’t pass,” Calou said. “The fact that we have to watch and read about how people are debating our ability to use a safe bathroom, where we go to learn math, to have our doctors provide basic and lifesaving healthcare, to have the supportive peers and adults in our lives taken away from us by not letting us experience teammates and coaches, is devastating to our wellbeing.

Calou continued, “The presence of supportive peers and adults is the number one factor in suicidality, and, as Haley’s parents said, the currents their daughter and other trans youth are swimming in are ones where we’re literally being told we’re dangerous and don’t deserve that care and support. Our hearts break with Haley’s parents and loved ones. Trans Lifeline is where trans folks and their loved ones often go when this news gets to be too much to bear. We want people to call us if they or a trans loved one is struggling, because having supportive trans community can help prevent crises in the first place.”

‘Her anxiety took over her life and became a very vicious cycle’

Alex’s last conversation with Haley was the night before she took her life. They had spent a couple of nights at a friend’s house, and apologized for being away so long. Haley told Alex there was no need for the apology, that it was all fine. They asked her how she was doing. Haley replied: “I’m alive. Not great, but alive.”

Christina says her last conversation with her daughter was about conquering the galaxy in Stellaris. “She was a tyrant, but a young tyrant, doing it for the people.”

Alex says they knew how their sister was feeling prior to her death; Haley had said months before she was feeling suicidal. Alex too was going through “a dark period” at the same time. In the week leading up to her death, Haley told Alex she was feeling “an intense amount of loneliness, to the point where if we were both sitting in the living room, she would burst into tears if I had gone to my room. She wanted more than anything to have people around her.” Alex begins to cry. “One of the things that makes it hard not to blame myself is that I knew what she was going through, how dark the place she was in was, that she needed me—and I wasn’t there for her. I wasn’t there for her when she needed me.”

“All of us feel some form of guilt and none of us should. So you are not alone,” Christina says to her child, softly. “All of us feel a sense of failure when it comes to Haley. Our daughter is dead. We should have been able to protect her.” She repeats again, “We should have been able to protect her.”

“We weren’t there to be able to do that,” says David. “We couldn’t get her to open up.” Christina talks about how Haley isolated herself, how she had traditionally forbidden touch, and “enforced these boundaries with no mercy. All of us became accustomed to them. We’re kind of a cuddly family. Then, later, she said she was feeling touch-starved and needed more.”

Sometimes it was hard, observing those boundaries as Haley’s mom, Christina says. “I was like, ‘Are you kidding? I can’t get a hug?’ But I had to remind myself ‘It’s not about me, it’s about her boundaries, and it’s important for me to get over myself and not be a crybaby.’”

Haley’s parents had struggled to figure out a solution, and to give Haley some hope for the future. “But her anxiety took over her life and became a very vicious cycle for her,” says Christina. “Along with that anxiety she was a little OCD. Her teachers would complain about the time she took writing individual letters to make them perfect. I think everything compounded everything else, and it became completely unmanageable for her. She was just tired. Tired of trying to figure it out, and of trying to find a way out that didn’t involve being hurt by people she didn’t even know. It just became too much for her.”

Their other children had also struggled with depression and mental health issues. “I had a constant fear of coming home after work or getting up in the morning and finding one of my children dead,” says Christina. “Haley and I talked about how she was feeling, and her seeking treatment. She was against it. I don’t know what to feel about that conversation. Short of dragging her to the hospital and trying to have her forcibly committed, she wasn’t going to go. And if I had had her forcibly committed, she would never have talked to me again. That would have been the end. You’re walking a tightrope. There’s no right choice.”

David says, “This new person seeking touch was coming to us the last couple of months. Even though she came to us about her suicidal thoughts and loneliness, at the same time I would get home from work, and she would run out and start talking about whatever game she was playing. We thought she was getting better.”

Lucy, the family’s beagle, barks. “Haley loved the hell out of her,” says Christina. “There was nothing, nor no-one that Haley loved more,” says Alex. (The picture accompanying her obituary shows Haley cuddling Lucy.)

In a later email, Christina says that since our conversation, she has “gone from angry to numb to broken in very rapid cycles, and what I want to share changes as the day goes on. I miss my daughter, and while I am angry at the entire world for her leaving us, I know the reality is that we failed her first and the most often, and that is a difficult thing to bear. She was more beautiful, more wonderful, more frustrating, than I could possibly ever convey.”

The family has not really circulated in the local community since Haley’s death, but is worried about what might happen when they do. “There are a few really good people here, but I haven’t stepped out much in the community, because I don’t want to hear what I think I’m going to hear,” says David. “There are a lot of people who did not know about Haley, and so I think there will be people who just don’t understand, and there are those people who refuse to process it.” His “biggest frustration” is that of the tributes on Haley’s memorial page online, the vast majority are from around the world, not the local community.

Day to day, Alex says working three shifts a week at a local cinema has been welcome. Its “awesome” owners use their preferred name and correct pronouns, and only query their choice of heels out of concern for them being on their feet for eight hours, offering to drive them home if they ever want to wear more comfortable footwear. Being at work is “nice little break” from contemplating the loss of Haley. But other than their job “I have lost my ability to function as a human being. Sometimes the idea of just doing the dishes overwhelms me. I am doing what I can.”

Alex has dreamt of Haley a couple of times. In one dream, “the strangest part is it’s as if my brain is telling me she is still here and survived what happened. In the second dream, she looks at me, tears covering her face, and says, ‘I don’t know how to be any more.’ It is as if every part of her is shattered.”

Christina says she got so used in the last few weeks of Haley’s life of seeing her daughter sitting in the living room, it is now strange not to. “It’s strange, it’s crap. You start the whole process again, reminding yourself your child has gone. It’s nice to hear people talking about her. It reminds me that she really was here. It’s grieving, I guess. My mind, wanting to make a doctor’s appointment for her, is having a hard time accepting what my heart truly knows, which is that she’s gone.”

David says he runs his father’s construction company, which has one employee, “so I go to work every day to make sure she actually gets paid. But if I didn’t have to do that I don’t think I would be. I don’t want to deal with people. It’s nice getting out of the house, but at the same time I don’t feel very distracted by work.” Christina says, “I feel even more distracted by it when I am at work.” David says he asks himself what the purpose of being at work is.

“To pay the bills,” Christina says, with a wry laugh.

“It just feels there is something more important I should be doing and I don’t know what that is,” says David.

‘How is it possible we are not going to see her again?’

Christina and David say the family continues to confront what life without Haley looks like, “and how this is going to be a lifelong experience and not a temporary glitch in the system which is what it feels like right now,” says Christina.

“You can say she’s not coming back, but that feels like an impossibility,” says Christina. “How is it possible we are not going to see her again? How can you be with someone for almost 19 years, and she’s just gone? It just doesn’t make any sense. Like I said, I’m angry, and struggling to be angry and not do harm to people at the same time. I’m sad and angry. My daughter took her own life, and I’m angry she felt like she had to. I’m angry that she felt like that was the best option available to her.”

To those who would have told her daughter there were other options, Christina suggests they “walk a mile in her shoes, see what she saw and the path laid out before her, before you tell anyone who is suicidal what they can and cannot do. Maybe try to understand where they are at. She was right about her life. She was going to have to fight tooth and nail for the rest of her life, and she was going to have to be on her guard wondering who was not going to respect her pronouns, her name, her gender. She was going to have to constantly be prepared to engage in battle with random people who had no business inserting themselves in her life, or to fight for equal and fair access to employment and proper healthcare.”

LGBTQ and trans activism of some kind may be a possibility for members of the family when they feel able to take such work on. When this reporter asks what, if anything at all, people could take from Haley’s death, David says, “Be better, stop being so self-involved and thinking everyone’s life is like yours—it’s not. Just understand everybody is their own person dealing with their own things, and you have no right to force your ideas on a situation you have no idea about. Be a good person to everybody.”

“And insist the people you empowered to make laws are better,” says Christina. “Insist they be decent to people as well. My daughter was an American citizen, but she was facing being treated like so many transgender people and members of the LGBTQ community in this country as if she was somehow deserving of less-than. Be kind. Always strive to lift up the people who need help, and always strive to lift them higher than where you are at. Push people up.”

Finally, Christina returns to “the silent people,” who say they support LGBTQ or trans people and their civil rights, but don’t speak or act volubly enough in their support—and even vote for those who undermine LGBTQ equality. “If the quiet people were louder, they would drown all those shitty people out.”

If you or someone you know is thinking of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or text TALK to the Crisis Text Line at 741741. Also: Trans Lifeline is at 1-877-565-8860.