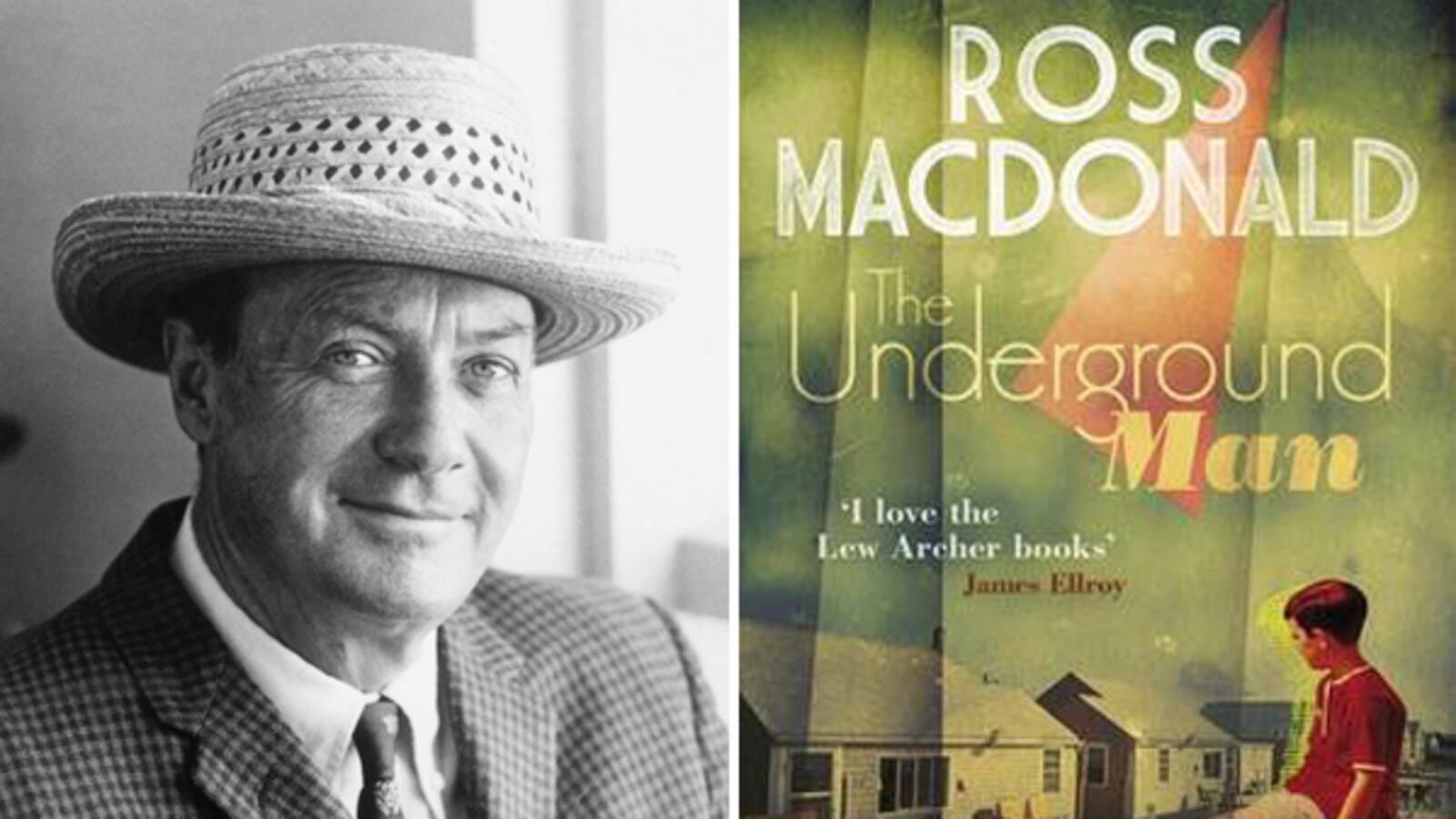

Throughout his career, Ross Macdonald—the pen name of Kenneth Millar—was hailed as the true heir to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler as master of the hardboiled mystery. But accolades beyond the reach of a genre writer still eluded him—until towards the end of his career, when he was finally acknowledged as not “only” a crime writer but a highly regarded American novelist. Macdonald subverted the genre by delivering the riddles and intricacies demanded of the crime novel in language that could be stark but also subtly nuanced and beautifully cadenced, while never slowing the requisite pace or diluting the excitement. In doing so he silenced those naysayers who had previously scoffed at the idea that the humble detective novel could possess any intrinsic literary worth. Praise finally came from both sides of the literary divide, with James Ellroy acknowledging his debt to Macdonald’s Lew Archer books and Eudora Welty lauding him as “a more serious and complex writer than Chandler and Hammett ever were.” Five of the gripping Lew Archer novels have just become part of the U.K. Penguin modern classics series. For many, this anointment is long overdue.

The Archer series ran from 1949 to 1976, and it is one of the later ones, The Underground Man from 1971, that is arguably Macdonald’s best. It opens calmly with Archer waking up, feeding peanuts to dive-bombing jays at his window and feeling a warm but ominous breeze. Such a slow set-up was typical: no crash-bang corpse-on-first-page histrionics. Gradually, though, Archer finds himself “descending into trouble” when he is employed by a beguiling blonde to track down her abducted son. To stoke the tension, forest fires are raging in the hills of Santa Teresa (Macdonald’s Santa Barbara) “like the bivouacs of a besieging army.” The case expands to include an AWOL father, a blackmailer, a couple of gruesome murders and a catalog of dark family secrets.

Those skeletons in closets were a tried-and-tested trope of Macdonald’s. A great deal of the fun in reading him is in locating the plot’s false bottom and sifting the many lies for nuggets of truth. Archer is adept at disinterring ghosts from the past to return and haunt his suspects in the present. Characters are never allowed to vanish completely. The Underground Man is full of overprotective mothers who will do anything to safeguard their errant sons. When Macdonald’s plots show signs of repetition (a mother also wants her son found in The Galton Case; so too does The Goodbye Look explore dysfunctional family drama and a decades-old crime) it is still a pleasure to lose ourselves in the tight, labyrinthine twists and turns. “I’ve never seen a fishline with more tangles,” remarks one character of the case in The Drowning Pool, and The Underground Man is just as knotty, to the extent that the denouement is as cathartic as it is surprising.

Chandler says in his introduction to his 1950 short story collection, Trouble is My Business, that the denouement should “justify everything” and that “what led up to that was more or less passage work.” The Underground Man is perfectly poised because Macdonald ensured that both his denouement and that passage work leading to it were equally charged. His ending is explosive but so too is the language that laces the narrative and the individuals that people it. Macdonald was inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s psychologically complicated characters and lauded by W. H. Auden, whose rich poetic imagery he borrowed. His detective fiction bears the stamp of their influence. The language ranges from the suitably noir-ish (“The striped shadow fell from the roof, jailbirding him”; a siren wails in the distance “like the memory of a scream”) to that unique lyrical wash Macdonald brought to the genre (“The night was running down like a transplanted heart”; “I caught a glimpse of the broken seriousness which lived in him like a spoiled priest in hiding”). His imagery does more than adorn; it also helps swiftly clinch a character for the reader. Archer inspects a young woman’s bruises (“the hash-marks of hard service”) and sums her up as “a dilapidated girl.” One man feels resentful and betrayed “like a sailor who had come to the edge of a flat world.”

And then there is Lew Archer himself, our first-person narrator, who Macdonald manages to render captivating enough to keep us reading while at the same time a dark horse. Throughout the Archer novels we are tossed piecemeal scraps about his identity. The Underground Man reveals him to be a loner whose wife walked out on him. But more interesting are the less specific tidbits, such as in The Chill, when we are told he has a degree from “the university of hard knocks.” Macdonald instills in his gumshoe the same end-of-tether world-weariness that Hammett and Chandler did in theirs, and yet Archer comes across as more humane than the flinty Sam Spade and more sober and remote than that sharp, wisecracking city slicker Philip Marlowe, and this is reflected in pages of wonderfully cool, fluid prose.

The Underground Man should enchant a new generation of readers and introduce them to a hero who, by his own admission, “sometimes served as a catalyst for trouble, not unwillingly.” Macdonald matters because of his ability to accurately depict the dire and dastardly things humankind does to itself and infuse them with a glorious poetic sensibility.