When the New York Post this week began publishing a series of stories on Hunter Biden, conservatives supporting President Donald Trump’s re-election campaign were openly ecstatic.

But veterans of cycles past urged caution, not just because the reports were opaquely sourced and—it appeared—dubiously obtained, but because if history is any guide, they’re not guaranteed to move votes.

“The nature of the news environment has just crowded out a lot of stuff,” Tim Miller, a former executive director of the GOP political action committee America Rising, told The Daily Beast. Miller, who left the organization in 2015, has since become a Trump critic.

Political opposition research is more an art than a science. At a technical level, it’s the act of finding out damaging information on an opponent and introducing it to the public. More colloquially, it’s mud-slinging.

In that regard, the stories in the New York Post have been oppo at its purest, most dastardly form. The original piece reported that Hunter Biden, the son of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden and the obsession of some of the president’s most fervent fans for over a year, may have provided a board member of a Ukrainian company a chance to convene with his father, hinting at (but by no means proving) a possible pay-for-play set up between the then-vice president and the business.

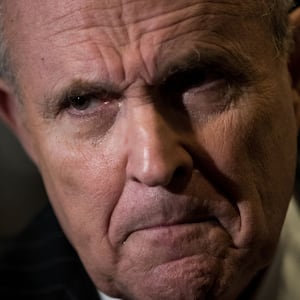

The biggest article came to be through highly suspect channels. As the piece recounted, Hunter Biden (or someone who appeared to be him) dropped off a damaged laptop at a store that repairs computers, after which the repair man found suspicious and incriminating data on the hard drive, decided to make a copy of it, and then passed it to an associate of Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s personal lawyer. Along the way, the FBI got involved.

Naturally, it made a splash. But that didn’t mean it would prove effective, Democrats said. Hail Marys can be completed, but often they aren’t.

“If this is the only thing they’ve done and this is the October surprise they were holding it’s a little unimpressive,” said Steven D’Amico, a political consultant who led the 2016 research team against Trump for American Bridge. “The fact that it’s in the Post is evidence of that.”

In some respects, the entire episode was reflective of how limited the president’s ability to manage news cycles has become. Up until the publication on Tuesday (and the subsequent publication of other items), Trump-aligned GOP operatives had seemingly abandoned prior behind-the-scenes efforts to convince reporters at major mainstream publications to write stories spotlighting negative information about Biden and his family. Instead, they’d opted to work with ideological allies in the media (of which the New York Post is one) and blast out snippets from their own platforms.

There are a number of reasons for the shift. Some Republicans supportive of the president said the deluge of news that has dominated the general election—twin health and financial emergencies, social upheavals, and now, a fast battle to fill a Supreme Court vacancy—has significantly complicated the business of getting a piece of oppo picked up and noticed.

“Over the past six months everyone was covering COVID and no one had time for anything else. Biden won the nomination,” one Republican operative familiar with research tactics said. “Then we went into lockdown, then protests started, [Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg] RBG died.”

“It just feels a little bit more difficult this time with the news cycle even more saturated than in the past,” the GOP source acknowledged.

Good opposition research, practitioners of the craft say, also takes time. The ideal hit is preceded by minor ones, establishing a narrative that a candidate is helplessly corrupt, totally out of touch, wildly incomponent or all of the above. When the big story finally breaks, readers will be more prone to believe it. But you still need to get those readers to read.

“You need a week for it to settle in,” said Matt Gorman, the vice president of the GOP-founded firm Targeted Victory. “Then you’re putting ads up. That’s another week for saturation and you’re at under a week.”

Finally, there is the question of whether any piece of oppo can break through in a balkanized media ecosystem, where news consumers are prone to distrust major outlets and, instead, decamp to ideological safe places.

“It has to do with the electorate’s view of the media and its credibility,” said Barry Bennett, a former senior adviser for Trump’s first presidential campaign. “People are more likely to believe what a friend posted on Facebook than what they read in The New York Times.”

The role that tech giants play in disseminating critical campaign stories was never more evident than this week, when both Facebook and Twitter put restrictions on the distribution of the Post item on their platforms. The stated reason by Twitter was that it violated their policies against the publication and spreading of “hacked materials.” And, sure enough, as Republicans cried foul, Democrats were quick to label the piece as “disinformation” with a connection to Russia, placed in a conservative outlet known to be friendly towards Trump.

“A computer store owner telling conflicting stories about how he supposedly copied a hard drive and gave it to Rudy Giuliani who gave it to a New York tabloid which then published what is likely Russian disinformation is not only not opposition research, it’s clearly too far fetched for even Ron Johnson's failed political hitjob of an investigation,” said Max Steele, senior communications advisor for the Trump War Room at American Bridge. “This story, like Giuliani himself, is a joke.”

While Democrats may be publicly laughing off the piece, they also appeared to recognize the political perils it could present.

Four years ago, reporters spent days digging through Clinton campaign emails put out from the chairman’s Gmail through WikiLeaks trying to distinguish verifiable nuggets from potential propaganda from Russia. After the election, the term “but her emails” became a euphemism for what Democrats believed to be an unfair equivalence between Trump’s statements and actions on the campaign trail and as a business leader, with Clinton’s decision to use a personal server while working in the top job at the State Department.

Eager to avoid a reprise of that, top Democratic operatives took to social media on Wednesday to chastise reporters who treated the Post piece with credulity. The Biden campaign’s national press secretary Jamal Brown, meanwhile, pointed to the action the company took to censor the story as de facto proof “that these purported allegations are false.” (Twitter, in fact, never made such a definitive judgement).

Bidenworld has experience navigating these waters. Even during the Democratic primary, Trump allies were making disproven and far-flung claims about unethical dealings on the part of his son. The president’s impeachment involved efforts to leverage the weight of the federal government to dig up precisely such dirt. Officials in the campaign, for their part, long saw the contest as a one-on-one duel against Trump even while running against others in the party, and in turn, spent months strategizing around attacks against Hunter Biden and his overseas work.

What makes the current charges different is both the context (now, the eleventh hour of the general election) and the content—coming, as it has, in the form of one massive, salacious, and potentially quite nefarious oppo-dump.

“Biden needs to be asked to address the specific, damning reporting in the New York Post and why he repeatedly lied to the American people. It would be nice to see reporters spend at least a 10th of the time investigating Joe Biden as they did covering the fly,” said Steve Guest, the rapid response director for the Republican National Committee, referencing a fly that landed on Vice President Mike Pence’s head during last week’s debate.