In the Russian city of Asbest in the Ural Mountains, life and work revolves around a dark pit more than 1,000 feet deep and six miles long, the largest asbestos-producing mine in the world. The future of every household in this community of about 70,000 people depends on chrysotile, the white mineral from which asbestos fibers are extracted—fibers so extremely carcinogenic that 65 countries have banned them.

The World Health Organization is unequivocal: “Exposure to asbestos, including chrysotile, causes cancer of the lung, larynx and ovary, mesothelioma (a cancer of the pleural and peritoneal linings) and asbestosis (fibrosis of the lungs).” The WHO estimated in 2014 that 107,000 people die each year because of asbestos related diseases (PDF). Worldwide, asbestos is responsible for about half of all the work-related deaths from cancer. In the United States every year mesothelioma kills from 12,000 to 15,000 Americans.

Not surprisingly, given such statistics, the company that operates the enormous mine, Uralasbest (also written as Ural Asbest), has lost many of its buyers and significantly cut down both its production volume and staff. Since 2013 more than 1,000 of some 5,000 workers have lost their jobs, and panic has gripped the city like an epidemic.

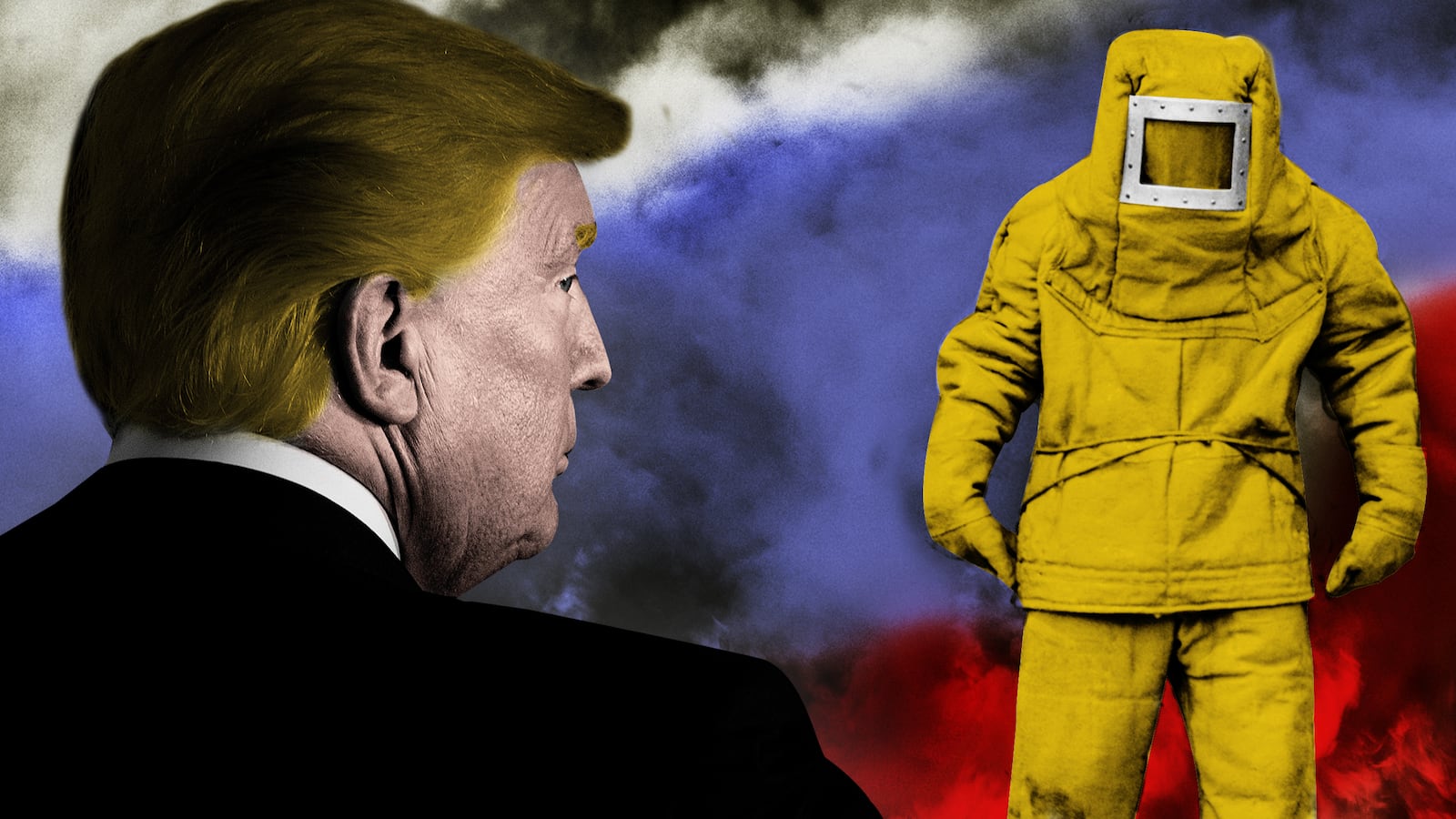

But Russia continues to insist that chrysotile is safe if used in controlled conditions—and so, enthusiastically and notoriously, does President Donald Trump.

In June, when the disgraced Scott Pruitt was still head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the EPA enacted the “significant new use rule” for asbestos opening the way for it to be used in a number of manufactured and imported products and judged on a case by case basis.

Two weeks later, after word reached Uralasbest, the company posted photographs on social media showing Trump’s face printed on neat packages of the product—a sort of special collectors’ edition of carcinogens. “Trump backs us up,” said the impromptu seal of approval. “Donald is on our side!” the Facebook post proclaimed.

But anyone in the asbestos business already knew that.

Trump’s fortune was made in real estate development, and long after asbestos health concerns led to regulations in the 1970s, he remained a fan of asbestos as a building material. In 1997 Trump said in his book, The Art of the Comeback, that asbestos was “100 percent safe.” In 2005, he floated the idea at a Congressional hearing that the World Trade Center buildings would not have burned and collapsed as they did on Sept. 11, 2001, if they’d had more asbestos in them. (In the event, they had enough to raise continuing health concerns for the people who worked in the rubble and dust after the attack.) His main concern appears to have been the cost of removing asbestos from his buildings, a process he has described as a scam that originated with “the mob,” which he said controlled that business.

In the town of Asbest, Yevgeny Shabanov, a local municipal deputy, confirmed to The Daily Beast over the phone that, “The chrysotile packages with Trump’s face on them are still in storage at Uralasbest,” although “at the moment it is unclear who is going to buy them.”

What is clear, is that people in Asbest are dying from asbestos related diseases, but cannot reconcile that fact with their desire to keep working and living there. In 2013, for an investigative project funded by the Pulitzer Center, I interviewed Asbest’s main oncologist, who told me he received 40 to 50 patients a day. One of his patients told me, “Every second person [at Uralasbest] has asbestosis—tiny fibers of asbestos—stuck in our lungs and covered with scar tissue.”

Long before it started putting Trump’s face on packages of asbestos, the city of Asbest had erected other monuments to the source of its livelihood. A huge asbestos rock covered in layers of silver fibers meets you on the highway at the entrance to the city and there is an immense stella, a shovel dated 1885, the year asbestos was discovered in the Ural Mountains.

Local miners are proud of their hard work, just as their parents and grandparents felt proud before them. In the early mornings hundreds of Uralasbest employees come to the pit to set off explosions, mine, excavate, package and transport the mineral, just as generations of miners did before them.

But even in remote regions of the Ural Mountains and Siberia people have begun to think more about their health and environment. Last year thousands of protesters joined rallies against plans by President Vladimir Putin's friend, Igor Rotenberg, to build an antimony factory in Asbest. Previously, in 2015 Rotenberg's National Antimony Company failed to open the production in the city of Degtyarsk, due to public revolt—locals believed that antimony was too toxic and dangerous and caused cancer. So, in a conspicuously cynical move, Rotenberg moved his project to Asbest, where the population already was affected by frequent cases of asbestosis and severe lung diseases.

In June 2017, a group of Asbest citizens submitted a petition to the Asbest Electoral Commission which said that antimony and its compounds with lead, arsenic and sulfur would destroy public health. At mass rallies activists proclaimed: "We are not slaves!", "Asbest is against Rotenbergs!", and "Our health is not for sale!"

The protesters won several court cases, including even in the Russian supreme court. “Luckily, we found a mechanism banning productions dangerous for our health,” deputy Shabanov told The Daily Beast. Production of antimony, that is. Not asbestos, which goes on.

Residents of Asbest are aware that wind spreads microscopic fibers of asbestos over the city, with all the dangers those entail. “My 64-year-old father, like many people in our city, suffers from asbestosis,” deputy Shabanov told The Daily Beast. “People think of health issues, of course, but at least for 10 more years our single-industry city will be fully dependent on the Uralasbest company and its business, so we carefully analyze which countries ban and which states, including USA are still interested in importing our goods.”

And for now, as some international headlines have pointed out, Trump seems determined to make asbestos great again.