Oklahoma’s Supreme Court has heard oral arguments from survivors and descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre as they push for reparations in a last-ditch legal effort.

The last surviving victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921—who are well over 100 years old—have fought hard to have their say in court, demanding reparations after Black residents claim the city subjected them to a brutal racial attack and decades of neglect.

Lessie Benningfield Randle and Viola Fletcher, both 109, appeared in the Oklahoma Supreme Court Tuesday in an attempt to appeal for reparations after enduring a violent carnage of Black residents in Greenwood, Oklahoma—also known as Black Wall Street.

“They were very focused,” attorney Sara Solfanelli told The Daily Beast, referring to the survivors as “Mothers” Randall and Fletcher. “They are fully with us. They knew exactly where they were, what was going on. They were excited to be there. They were paying attention and really know what’s happening in a way that they feel very strongly about this case.”

“We are grateful that our now-weary bodies have held on long enough to witness an America, and an Oklahoma, that provides Race Massacre survivors with the opportunity to access the legal system,” Randle and Fletcher said previously in a joint statement. “Many have come before us who have knocked and banged on the courthouse doors only to be turned around or never let through the door.”

“Now, our pursuit of justice rests in the hands of our Oklahoma Supreme Court. They have the power to open the doors of justice and give us the opportunity to prove our case.”

The legal team for Randle and Fletcher want the Oklahoma Supreme Court to take the case to trial so that the survivors can tell the true story of Greenwood and how it has affected generations following the attack.

“We will show you how the current state of events of Greenwood trace back to the massacre,” attorney Randall Adams told The Daily Beast. “Without a trial… the sheriff's department can get up and assert, ‘Here’s the truth. Don’t even let them have a trial.’ It’s so offensive in that aspect.”

During Tuesday’s hearing, lead attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons really drove home to the court why the case was not specific to 1921 and how the attack had lasting effects for over a century.

“It does not matter that the massacre happened in 1921. What matters is that the property is still blighted. There’s still vacant properties. The public nuisance is ongoing, causing the Greenwood neighborhood to suffer its health, safety, comfort, and repose or feel less secure,” he said. “You have defendants who have never ever been held legally responsible for the massacre. And to this very day, these defendants denied that they perpetrated the massacre. They deny that they created a public nuisance. They deny that they have any legal responsibility to clean up the public nuisance, the blighted neighborhood of Greenwood that they created.”

But also, Solomon-Simmons made sure to highlight how important it was that survivors from the original attack were still around to share their experiences.

“These two plaintiffs… are the only two living survivors of the massacre. No one else in the world has the injuries they have,” he said. “We want these two survivors to see justice in their lifetime.”

Randle and Fletcher, along with survivor Hughes Van Ellis Sr. who passed away in Oct. 2023, initially filed a lawsuit against the City of Tulsa, the Tulsa Regional Chamber, the Tulsa County Board of Commissioners, the sheriff of Tulsa, and the Oklahoma Military Department in 2020. However, Tulsa District Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the case with prejudice in July 2023.

According to local outlet ABC 5 Oklahoma City, attorneys for Randle and Fletcher filed an appeal in August, and in February the Oklahoma Supreme Court decided to hear the case.

“It breaks my heart that even after suffering through a state-sponsored atrocity and its demoralizing aftermath, the last two Tulsa Race Massacre survivors are devoting the fleeting time they have left to a battle that the defendants hope will break their spirits,” Solomon-Simmons said previously in a statement. “But the City of Tulsa’s shameful plan will not work.”

Journalist Victor Luckerson who has looked deeply into the history and ramifications of the Tulsa massacre said that the case sets a precedent for similar stories involving systemic racism and their generational effects.

“When you look at it in a macro sense, Tulsa and Oklahoma as a state have been trying to deny their accountability for what happened in Greenwood for more than 100 years,” Luckerson told The Daily Beast in an interview. “The fact that these arguments can exist for that long kind of illustrates the fact that the city as an institution [had] never really taken full accountability for what happened in Greenwood.”

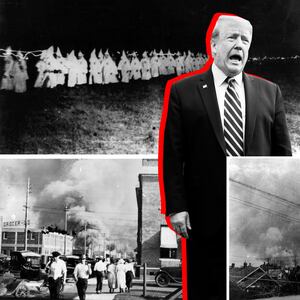

The Tulsa race massacre sparked in 1921 when a young Black shoeshiner was accused of assaulting a white teen girl while he was employed at a hotel. Though there was never any proof of the accusations, the young man was arrested and there were rumors that a white mob planned to snatch him from the local jail to lynch him. Black residents heard about the plan and tried to intervene, marching to the jail to protect the shoeshiner. But all hell broke loose after a gunshot was fired, and the entirety of the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood was razed in flames.

Businesses were demolished, homes were ransacked, and Black residents who were not killed were forced to live in a makeshift internment camp within the city and had to abide by a curfew and obtain passes to leave, like enslaved people on plantations. Insurance companies failed Black residents and business owners, and Greenwood was never fully rebuilt to its original magnitude. Instead, it was reconstructed in a series of shanties that the city eventually took over during an urban renewal scheme of the 1970s because the area was considered to be too blighted and an eyesore to the rest of Tulsa.

According to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, around 300 people may have died, 800 were injured, and mass graves continue to be discovered.

The Brookings Institution reported that Greenwood, or Black Wall Street, experienced more than $27 million in damages in today’s currency.

“I don't think [I] understood until I got on this case how powerful real generational trauma is and really how the massacre has absolutely affected who they are, how they were raised,” Solfanelli explained. “[Descendants’] great-grandparents or their grandparents or parents who survived it were too scared to talk about it, but how it permeated their lives.”

Luckerson, the author of Built From the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street (2023), said that during much of his research he discovered many of the original lawsuits filed by Black residents just after the massacre in 1922 and 1923 were similar to what the survivors and descendants want today.

“With this lawsuit in particular, I thought it was interesting that the lawsuit goes beyond the scope of the race massacres,” Luckerson added. “It talks about urban renewal. … It talks about the history centers and museums and sort of monetizing the massacre and who gets to make money off of it.”

Luckerson made it an important note in Built From the Fire to not focus solely on the act of the massacre itself. Instead, he transcended the violence and how it carried on into the academic system in Tulsa and education of Black residents, the forever disappearance of a wealthy Black community and entrepreneurship, the harsh judicial system, gentrification and an attempted erasure of the historic neighborhood, and into how the area responds to current social and political issues like Black Lives Matter and presidential elections.

“I think it's important that people are sort of getting that full picture of the damages that have been done,” Luckerson told The Daily Beast.

Luckerson, who’s from Montgomery, Alabama, claims that although Tulsa shares a dark, racist history like his hometown, Tulsa’s brutal past has not been “processed,” and the wounds of massacre descendants are still fresh because “they have to live with the trauma everyday.”

“[Montgomery’s] history has been so widely analyzed that it kind of feels like American history,” Luckerson said. “The emotions are much more raw in Tulsa because of this lack of justice, lack of accountability, lack of acknowledgement.”

Despite the lengthy process the case has taken, Solfanelli and Adams said that it will still be a while before the supreme court decides whether or not to hold trial.

“It’ll probably be a minute before there’s a decision,” Adams said. “But this is such a moment: The survivors coming to the state capitol, sort of looking at the [Oklahoma] Supreme Court in the eye, the supreme court seeing them. This is also truly the last stance. So, if the supreme court dismisses [it], the case is completely over. We cannot appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court because it's state laws, not federal law. So, this is it.”

“Another element that is important and very interesting is the way that [the] Greenwood community is… just as engaged,” Solfanelli said. “All of the local Greenwood community and descendants have been a part of this from the beginning and have continued to be and just aren't going anywhere.”