I asked Google to find stories about a potential challenge to Hillary Clinton’s presumed Presidential run, and in about a third of a second, I was offered 37,500,000 of them.

There’s no point in recycling the same list of possible foes, nor the competing arguments for and against a contested nomination. (There’s an excellent take that appeared on this site last September: Yes, sometimes a contest be invigorating—Reagan in ’80, Clinton in ’92, Obama in ’08—and sometimes it can open wounds that never heal—Goldwater in ’64, McGovern in ’72, Ford in ’76, Carter in ’80.

But if you’re looking for a telling example of a politically helpful primary challenge, there’s no better example than one that should have happened, almost happened, but didn’t.

It happened—or didn’t—in 1988, when Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis was grinding his way to the Democratic nomination. Two potentially major rivals had long since been sidelined: Senator Joe Biden by charges of plagiarism, and former Senator Gary Hart by—well, you know. Those in the race—Senator Paul Simon, Rep. Dick Gephardt, Rev. Jesse Jackson—were far behind. Another dark horse, Tennessee Senator Al Gore, was finding little traction in his efforts to become a centrist alternative.

Gore’s last stand would be in the New York primary. On April 12, during a debate sponsored by the Daily News, Gore confronted Dukakis with an issue that had not surfaced at any time during the campaign. Why, Gore wanted to know, did Dukakis support a state program that gave weekend furloughs to convicted criminals, even after some of those prisoners had committed crimes while on furlough? The audience booed the question, Dukakis went on to win the New York primary convincingly, and Gore dropped out of the Presidential race.

If you’re familiar with recent political history, you know what happened next. James Pinkerton, a policy aide in the campaign of George H.W. Bush, found press reports that detailed the story of Willie Horton—a convicted murder who, while out on furlough, had terrorized a Maryland couple and raped the woman. Bush campaign chief Lee Atwater watched focus groups move sharply away from Dukakis when they learned of the story. (Atwater said at one point that by the time the campaign was over, voters would think of Horton as Dukakis’ running mate). Bush himself raised the furlough issue—without mentioning Horton by name—during his RNC acceptance speech, and the campaign featured an ad showing showing men in prison garb moving through a revolving door.

Then an independent campaign—the National Security Political Action Committee—put on its own ad, showing the mug shot of Willie Horton looking very menacing and very, very black. To this day, Bush media maven Roger Ailes adamantly denies that he or the campaign had any role in the Willie Horton mug shot ad. And to this day, liberals in the political world use the name “Willie Horton” to describe an appeal to primal racial fears.

Now consider a different question: suppose Al Gore had stayed in the race. Or suppose another of Dukakis’ opponents—Jesse Jackson, most intriguingly—had kept the question alive. Was it really a good idea to furlough convicted murderers? Was it a mistake to veto the bill that would have curtailed such furloughs? For a one-time political operative like myself, it offers the possibility of a rarely seen event in campaigns: the open, frank admission of a mistake.

“Candidates always like to tell you what they did right,” I imagine Dukakis saying. “Now I want to tell you what I did wrong—and what I learned from it. Giving prisoners a chance at redemption is a good idea; but we were too careless, and innocent people suffered because it it. I think it taught me to ask harder questions about good intentions; it’s a lesson I intend to remember as President.”

I’m not suggesting that it would have changed the outcome of the 1988 election; and you have to question the overall tactical shrewdness of any campaign that sent its candidate riding around in a tank looking like Snoopy heading out to fight the Red Baron.

What the “missing furlough” debate does tell us, however, is that a candidate who is not confronted by a tough policy challenge in a primary may wind up unprepared for that challenge in the fall, which of course is the moment when it matters most. Republicans, for example, may have found intra-party attacks on Mitt Romney’s business career offensive; they are, after all, the party of the “builders”. Democrats, as Romney should have remembered from his campaigns in Massachusetts, have no such compunctions. Democrats will not take kindly to criticism of public employee unions, which provide cash and foot soldiers for the party; a candidate too close to those unions should not be surprised to find herself under fire come Autumn.

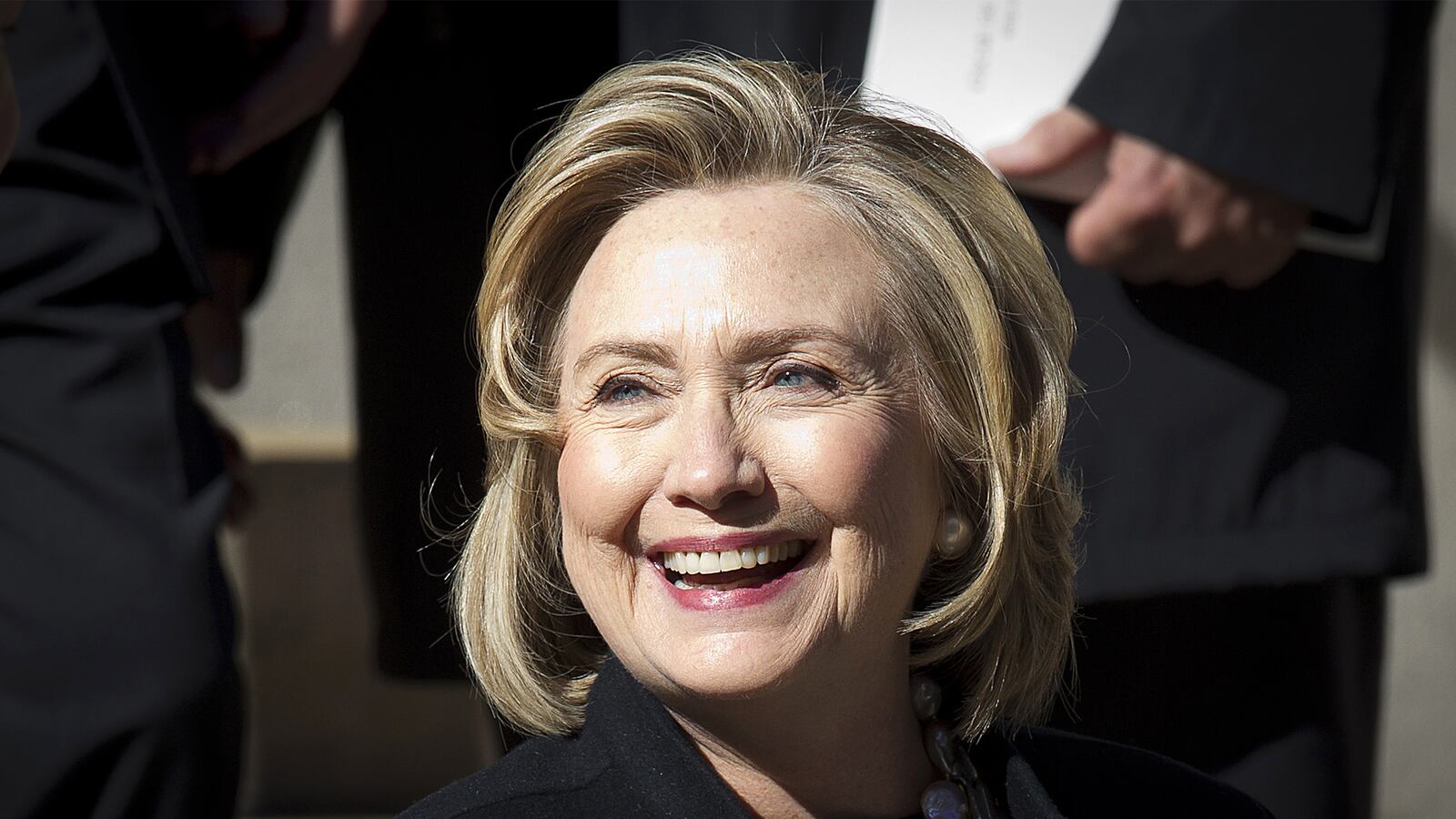

How does this apply to She Who Must Always Be Named?

Much of the conversation has focused on potential challenges from the Left. Is Clinton too close to the Wall Street-Goldman Sachs wing of the Democratic Party? Does she need to distance herself from the deregulatory policies of the Bill Clinton years? Is she too hawkish for the activists who helped make her vote for the Iraq War so costly back in the 2008 campaign?

It would be even more helpful to her election prospects if she were confronted in the primary with questions more likely to be raised by the Republican nominee in the fall: was the Russian “reset” policy naive? Was it wise for the US to leave Iraq without even a residual force in place? What specific aspect of US foreign policy was changed for the better under her watch? Does she agree that the Affordable Care Act was offered to the public under false pretenses?

If these issues raise uncomfortable questions for Democrats, Clinton has reasons not to be too unsettled. She no doubt remembers that another candidate for President had to explain his break with many root assumptions that Democrats held about issues ranging from crime to trade to welfare. And that debate during the 1992 primaries worked out pretty well for the nominee.