For Chileans, 9/11 is a date with a meaning all its own. That’s the day, in 1973, when combat troops under orders of Gen. Augusto Pinochet attacked the La Moneda presidential palace, toppling the democratically elected government and installing a 17-year dictatorship. In that time, more than 3,000 Chileans are known to have died or “disappeared” at the hands of official security forces. But now comes word that Chile’s notorious guerra sucia (dirty war) may have claimed yet another victim, in a crime as telling as it was brazen.

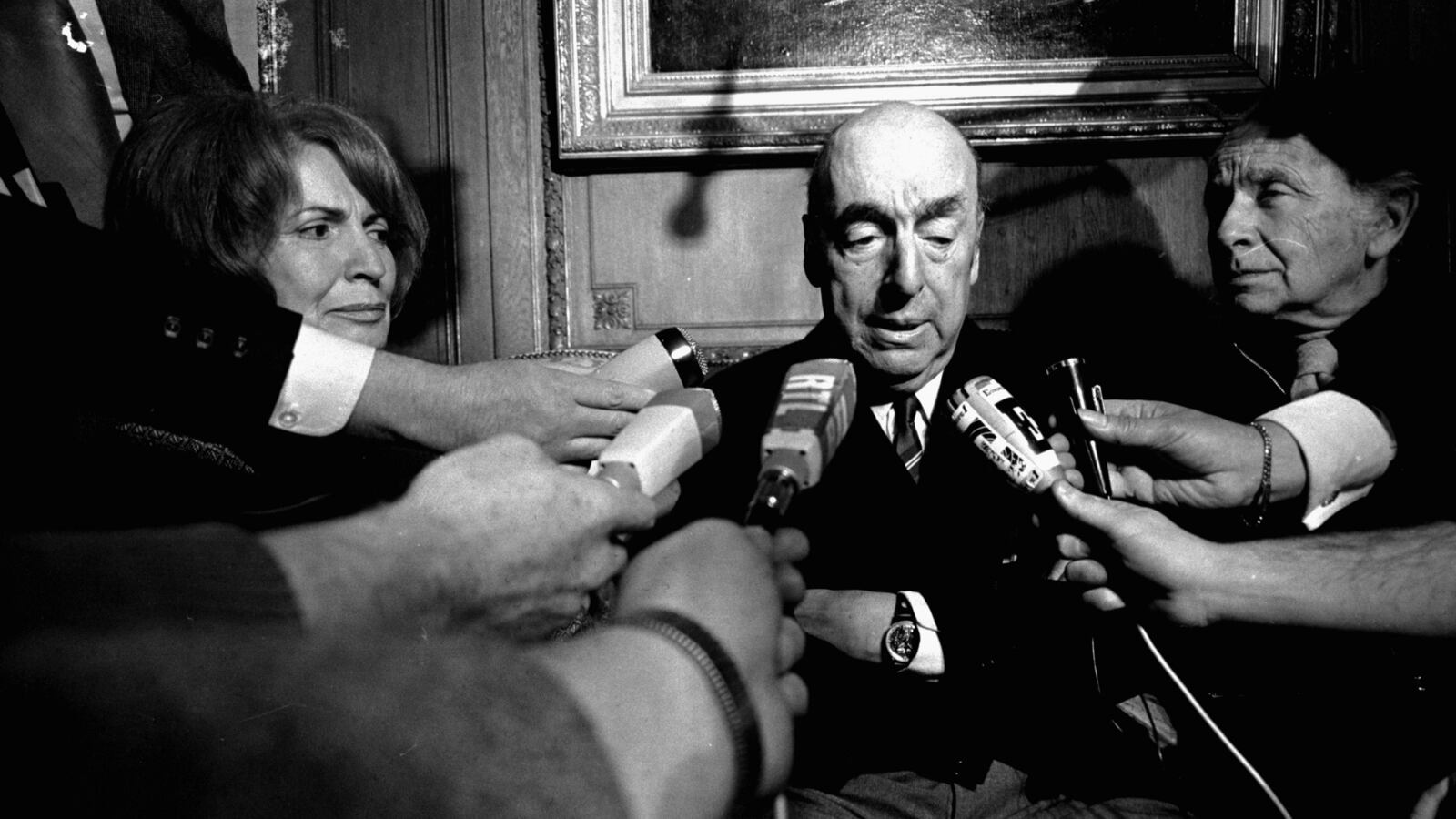

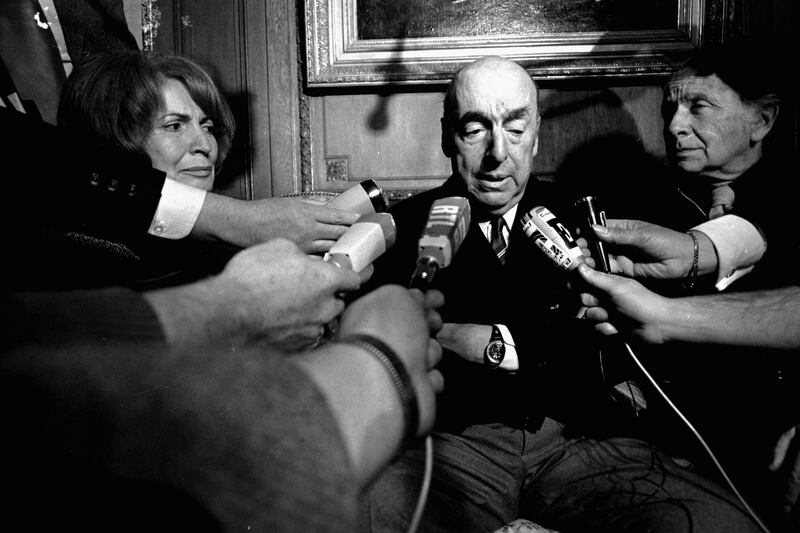

On Monday, Chilean medical examiners dug up the remains of Pablo Neruda, Chile’s most famous poet, who died a few days after the coup. At the time, the Nobel laureate, then 69, was reckoned to have succumbed to prostate cancer, complicated by the trauma of witnessing friends and compatriots die during the bloody coup. The Neruda family subscribes to this version of his death to this day. But driven by recent evidence, Neruda’s political heirs now believe he may have been poisoned on orders of the Pinochet government, anxious to silence a world-famous critic.

The poet’s remains were removed from a grave in a flower garden behind the Neruda home on Isla Negra, a placid village on Chile’s craggy Pacific coast, some 70 miles from Santiago, and transferred to a medical facility in the capital, where forensic testing will begin.

Horror stories about state crimes are nothing new in Chile, where “Generalissimo” Pinochet ruled with an iron hand from 1973 to 1990, but whose deeds until recently were more whispered about than known. Recently, truth-telling commissions have lifted the cloak of official silence on the dirty war that saw mass arrests, torture, political kidnapping, and outright execution or “disappearance” of dissidents. The full extent of the official crimes are now on exhibit at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, inaugurated in Santiago, in 2010, by then-president Michele Bachelet, who was tortured herself and lost her father to the dirty war.

But few had counted Neruda among the dictator’s victims. Suspicions bloomed in 2011 when a former chauffeur and bodyguard, Manuel Araya, began to recount details of Neruda’s later years, and especially his final days. Long suffering from prostate cancer, Neruda was undergoing treatment in late 1973, and on Sept. 20 checked into the hospital with a urinary infection.

That’s when Araya received a phone call from Neruda, who told him from the hospital that he had taken a sudden turn for the worse after a physician gave him an injection in the abdomen. Three days later, on Sept. 23, he was dead. Friends and associates claim that Neruda, though long afflicted by cancer, was not in agony or near death upon entering the hospital. “As long as I am alive, I will not alter my story,” Arraya told the BBC.

Arayas’s statements galvanized Chilean socialists, who began to press for a full investigation. Medical experts caution that it may be difficult to prove, 40 years later, whether or not Neruda died of natural causes. However, Chilean judge Mario Carroza granted a request by the Chilean Communist Party, which Neruda served briefly as a national senator, to exhume the poet’s remains for medical examination.

A lifelong leftist and a former diplomat, the bard revered for his lyric verse and vivid love poems also was a close friend to president Salvador Allende, who killed himself during the siege rather than surrender to the coup makers.

Araya said that Neruda was badly shaken by the coup, in which many of his friends had perished, not least after soldiers invaded his home. He also reported that a Chilean warship had sailed into the waters off Isla Negra, allegedly training its guns on the poet’s house. It was common knowledge that Neruda had planned to go into exile, in Mexico, and reportedly hired a plane that was on the runaway even as he was hospitalized.

Neruda’s backers charge that Pinochet sought to eliminate the poet rather than risk allowing a world-renowned political gadfly to spread dissent on foreign soil.