They were three brothers, members of a pacifist Hutterite sect in South Dakota. Arrested for being conscientious objectors during World War I, they were sent to Alcatraz, at that time a military prison. When the brothers refused to don uniforms, because it symbolized submission to the army, they were chained to their cell bars, arms crossed and standing, for eight hours a day.

Fed only bread and water, the brothers were given no blankets, beds, or other furniture, and were occasionally whipped when chained. Rats roamed their cells, moisture from a cistern dampened their walls, and the only lights were in the corridor. Finally transferred after four months to another military prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, they were marched uphill and, sweaty, forced to undress and stand in the chilly night air for several hours. Two of the brothers died several days later, and when the widow of one showed up and asked for his coffin to be opened to view his body, she was horrified to find it clothed in the military uniform he had refused to wear while alive.

That’s just one example of the brutality and callousness of what might be the bleakest period in American history—the years 1917-1921, the subject of American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, the latest book from noted historian Adam Hochschild.

“The sheer savagery and brutality of what people endured during this era” is one of the things that surprised him most during his research, Hochschild said in an interview with The Daily Beast. “Particularly the lynchings of Black people, and other types of brutality used against conscientious objectors in prison.” Why this happened, he says, is because “we were not too far away from the brutality of the frontier. There was a kind of brutality that comes from being close to an expanding frontier, and a tradition of vigilante justice on the frontier. Something of that spirit spread into the whole country, and entering WWI unleashed so much of this brutality, even though the United States had not been attacked.”

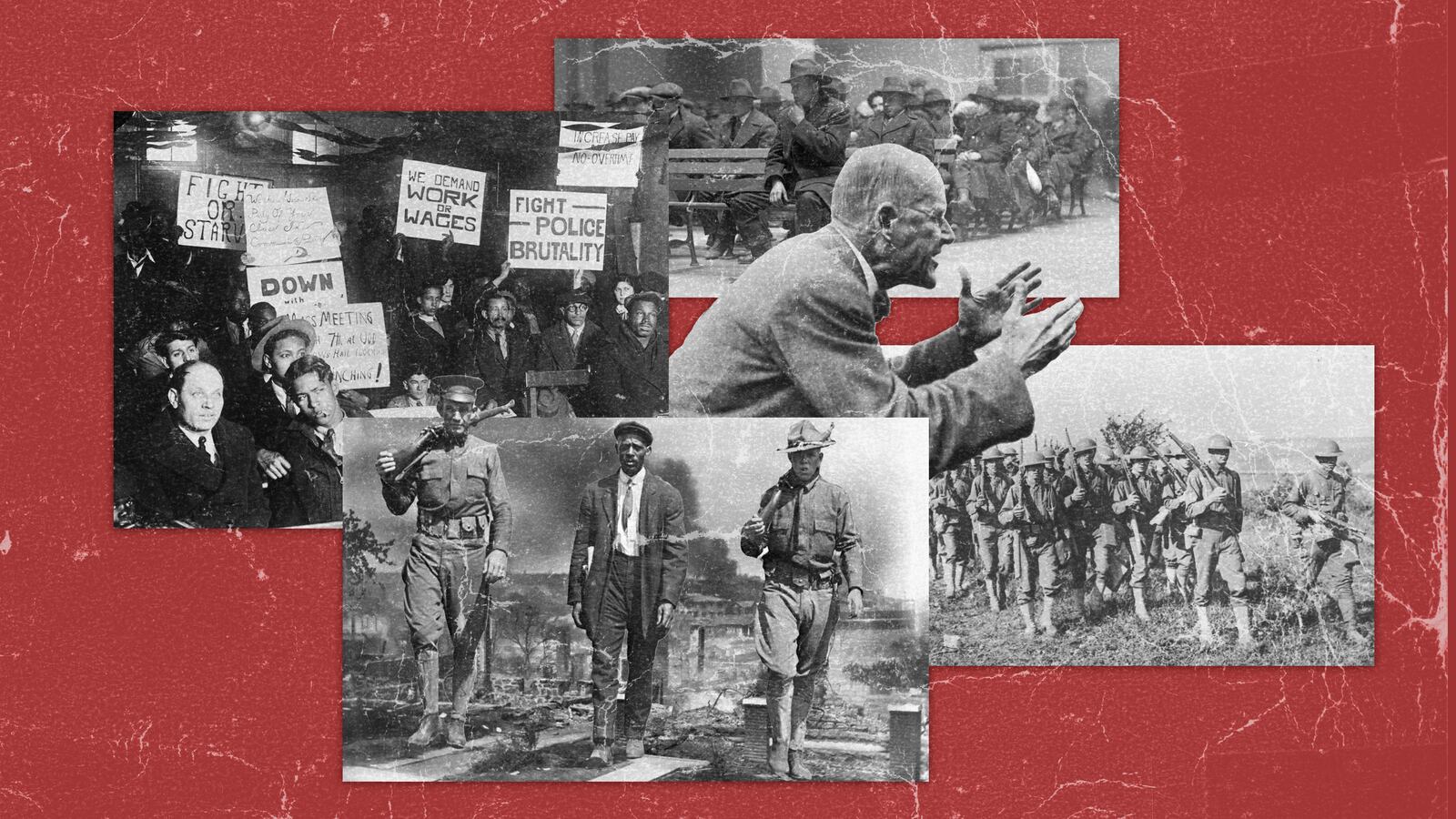

American Midnight is the kind of book the right-wing group Moms For Liberty would probably want banned from school libraries, because it shows white nativism at its most toxic. The years it covers saw a crackdown on leftist groups like the Socialists and International Workers of the World, the latter of whom were involved in the largest civilian criminal trial in U.S. history; massive race riots in cities like East Saint Louis and Tulsa, and lynchings throughout the South; censoring of the leftist, foreign-language, and Black press, which were banned from the mails; battles against organized labor; prejudicial moves against Jews and immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe; and the rise of the American Protective League, a massive right-wing vigilante force that was an auxiliary of the Department of Justice.

The psychosis of the era was, in fact, so extreme it almost seems surreal. In Bisbee, Arizona, an army of vigilantes forced over 1,000 striking miners into cattle cars, hauled them nearly 200 miles into New Mexico, then drove them into an army stockade. In East St. Louis, white mobs invaded a Black neighborhood, set fire to more than a dozen blocks, killed at least 100 residents, and forced more than 7,000 to flee for their lives. And in the Palmer Raids of 1919/1920 (named after then-Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer), nearly 10,000 so-called “subversives,” many of them Jews, Poles, or Italians, were arrested—most without warrants, often beaten and denied legal representation, in what one historian called “arguably the greatest single violation of civil liberties in American history.”

“Because we are a country that has always been receiving new waves of immigrants, there has been this tension between those who got here earlier, and the new waves,” says Hochschild of the Palmer Raids, “and there has been a tendency to blame the new waves for things going wrong. When people feel they are lagging behind, they want to blame somebody.”

Not that there weren’t people who fought against this repression. Anarchist Emma Goldman spoke out against the war and conscription, but was eventually arrested for “conspiracy to interfere with the draft” and ultimately deported. Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs also refused to keep quiet, was arrested, incarcerated, and ran for President in 1920 from his jail cell, earning 6 percent of the vote.

(President Woodrow Wilson, who hated Debs, refused to pardon him, even after the war had ended. It wasn’t until Warren G. Harding became president that Debs was released from prison, with Harding telling a reporter, “Why should we kid each other? Debs was right. We shouldn't have been in that war.”)

And then there was the greatest American hero you’ve probably never heard of: Louis F. Post. A founding member of the NAACP and a supporter of the campaign that created Labor Day, Post was acting Secretary of Labor, a position which also made him head of the Immigration Bureau, when he invalidated 3,000 of the Palmer Raid arrests for various reasons (no access to lawyers, no deportation warrants). And out of over 2,000 more deportation cases, he allowed less than 20 percent to go through. This infuriated the House Rules Committee, which tried to impeach him. But when testifying, Post gave such an impressive lesson on immigration law that the committee dropped the proceedings.

So why isn’t this guy better known?

“His heroism was within the bureaucracy,” says Hochschild, “he was not leading a march, or anything like that. Post orchestrated the Twelve Lawyer Report (researched by a dozen attorneys that detailed the abuses of the Palmer Raids), but he stayed in the background, and eliminated from his papers that he had any contact with these folks. And he also orchestrated a case in Boston (Post encouraged a test case in which a federal judge freed potential deportees while slamming the government’s overreach). He was trying to conceal his efforts, but there were front-page headlines at the time. Still, that was 100 years ago.”

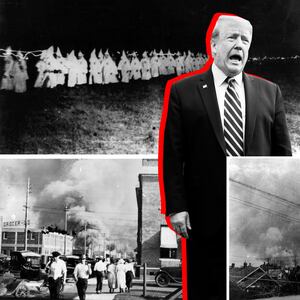

Reading American Midnight, it becomes obvious that some of the issues that were flashpoints in 1917-1921—immigration, racism, labor strife, compromised media—have their echoes in today’s world. Given that, Hochschild says there are significant similarities and differences.

“A lot of things are the same,” he says, “but one difference is who the villains are. At that time, immigrants were primarily Jews, Italians, and Poles, none of whom had become ‘white,’ so to speak. Today it’s immigrants from Latin America. In those days Red-baiting was really extreme, and today there really is no more communism, but that doesn’t stop the right from Red-baiting anyway. And another difference is a more positive one: the daily press in those years was awful, they pretty much printed what government spokespersons said. Today’s press is more skeptical.”

Still, American Midnight raises the question of whether the insanity of the era it discusses can ever happen again. On this point, Hochschild is surprisingly optimistic. “I’d like to think it’s not inevitable,” he says, “we can avoid it. Good journalism is incredibly important, and not taking what government and demagogues say for granted, Having organizations that don’t let people get away with stuff, like the ACLU, which was born during this period. And 100 years ago there really weren’t civic organizations dedicated to maintaining civil liberties.”

Ultimately, Hochschild wants the readers of the book to come away from it with the understanding that eternal vigilance regarding our rights is important. “We have to watch this doesn’t happen again,” he says. “It’s not about a single person or party. We’ve been through these things before, and we have to be aware of them, and aware of what causes stress in this country.”