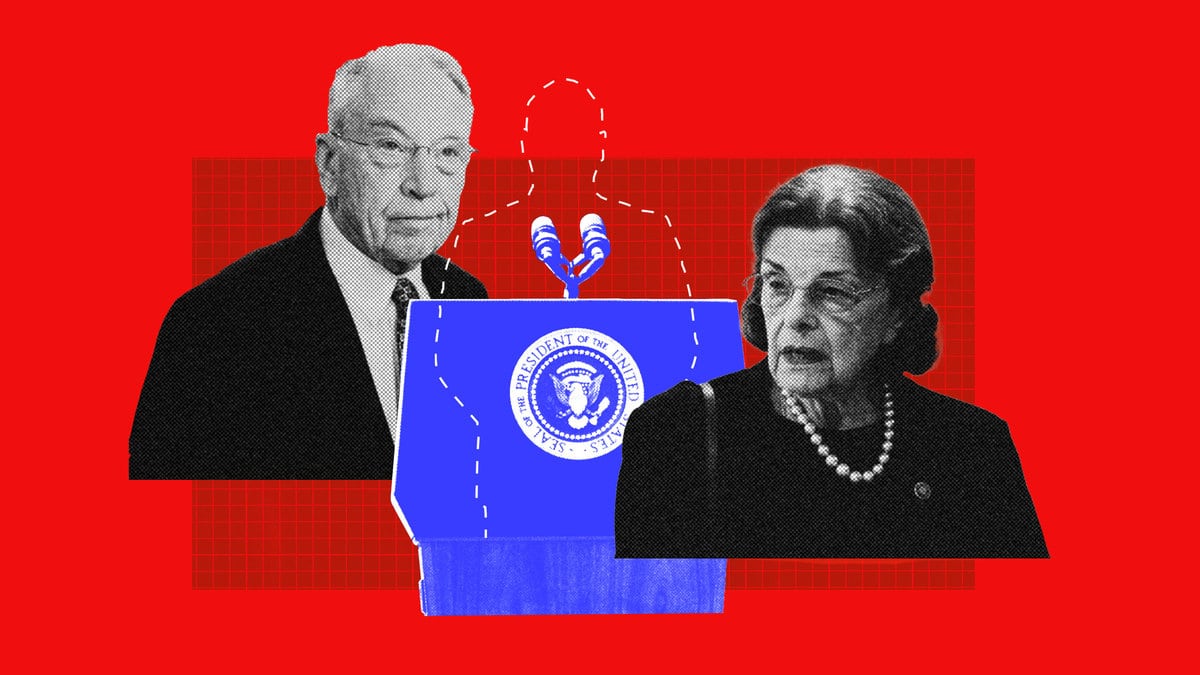

On Jan. 3, the formal leadership of the Senate is poised to pass to one of two 89-year olds: Republican Chuck Grassley of Iowa or Democrat Dianne Feinstein of California—who are in line to become president pro tempore of the Senate depending on which party holds the majority.

The job of president pro tempore of the Senate doesn’t usually get much attention. It is, in effect, a ceremonial role which by tradition is given to the longest-serving senator in the majority party. Constitutionally, the job is to preside in the absence of the vice president, who is the regular president of the Senate. In practice, neither vice presidents nor presidents pro tempore actually spend much time presiding, a tedious task delegated to junior members. And practical political power is wielded by the Senate majority leader, who actually sets the agenda and runs the chamber.

But there’s a problem lurking in this little-known position, one which is now being highlighted by the advanced ages of both Feinstein and Grassley. The former has even suggested she might decline the position as rumors swirl about her declining mental acuity.

ADVERTISEMENT

The problem is that the president pro tempore is, under current law, third in line for the presidency after the vice president and the speaker of the House. In the catastrophic scenario where the senior levels of government have been devastated by war or terrorism or assassinations, the most powerful office in the world could suddenly be in the hands of a geriatric senator of dubious competence.

Congress Gets It Wrong, then Right, then Wrong Again

The Constitution provides that in the event of death or other vacancy in the presidency, the vice president becomes president. This has happened nine times as presidents have variously died from natural causes, been shot and killed, or, in one case, resigned in disgrace.

There has never been an instance when both the president and vice president were out of commission at the same time, but there have been several close calls. The Constitution gives the task of determining succession beyond the vice president to Congress, which has done so with the Presidential Succession Act.

The first version of this law, passed in 1792, specified two backups: first, the president pro tempore of the Senate, and second, the speaker of the House. But this wasn’t an uncontested decision. No less of an authority than James Madison objected that it was unconstitutional, that members of Congress were not “officers” in the constitutional sense and that, furthermore, inserting legislative leaders violated the separation of powers. But Madison’s objection did not carry the day.

This was how the law stood until after the Civil War, even though both positions were often vacant during long stretches when Congress was not in session. Several times, the vice presidency was also vacant, with no way to fill it until the next election. That left the president with no designated successor at all for months at a time.

Worse, the conflict of interest became apparent in the first presidential impeachment, of Andrew Johnson in 1868. The vice presidency was vacant since Johnson had become president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. This left the president pro tempore, Benjamin Wade, next in line…and also with a vote in Johnson’s Senate trial. The unseemliness was obvious and the situation, along with Wade's perceived radicalism, may have contributed to Johnson’s acquittal by a single vote. (Wade voted to convict and thus to make himself president.)

In 1886, Congress finally got it right, in line with Madison’s wishes. Congressional leaders were removed and instead presidential succession would run through the Cabinet, starting with the secretary of state and proceeding through each of the other department heads. This guaranteed policy and partisan continuity and also provided an ample list of potential successors.

That was how things stood until 1947, when the vice presidency was again vacant with the accession of Harry Truman after the death of FDR. Truman was uncomfortable with having the secretary of state next in line. He considered it undemocratic for a president to appoint his own successor. Congress, for rather more egotistical reasons, agreed. The Cabinet was retained, but ahead of the secretary of state were inserted the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore, in the opposite order of the 1792 law. The House passed the bill with little debate and humorous cheers for Speaker Sam Rayburn.

The Presidential Succession Act was first passed in 1792 under the objection of James Madison.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyYou Have One Job, Presidential Succession Act

Since the adoption of the 25th Amendment in 1967, vice presidential vacancies are much less likely, since the office can be filled by presidential appointment with confirmation by Congress (thus rejecting Truman’s objection about a president choosing his successor). This was how Gerald Ford became president, first replacing Spiro Agnew as VP, and then Nixon a few months later. But the 1947 succession act remains in place, and it has serious constitutional and practical defects.

The most glaring flaw is the absurdity of including president pro tempore, a position invariably held by a senator of extremely advanced age. At the most extreme, in 2001, it was held by Strom Thurmond, then 99 years old. The current holder of the role, retiring Patrick Leahy of Vermont, is a relatively youthful 82. And on the opposite side of the Capitol, the current speaker of the House is also an octogenarian.

There are other problems beyond possible decrepitude. Madison’s constitutional objection still carries weight among legal scholars, who continue to debate the constitutionality of the succession act. There are good-faith arguments on both sides, working from admittedly vague and perhaps even contradictory constitutional text regarding what counts as an “office” or “officer.” But the mere existence of the dispute defeats the whole purpose of the law: to provide a quick, definitive, undisputed transfer of power.

Consider a worst-case scenario: if the events of Jan. 6 had gone catastrophically worse, possibly producing mass casualties, and Congress thereafter failed to certify the 2020 election results before Inauguration Day on Jan. 20. Or, less dramatically, if Trump’s supporters in Congress had simply run out the clock by raising repeated frivolous objections to the votes of all 50 states.

When Trump’s term expired, the result could have been a showdown between Nancy Pelosi and Mike Pompeo, the latter advancing the argument that congressional succession is unconstitutional and so he, as secretary of state, was the highest-ranking valid successor. Not a pretty scenario.

Cabinet succession also avoids the possibility of an abrupt partisan change in the presidency, or even worse, political incentives for assassination. Cabinet members are appointed by the president to carry out their agenda, work with the president to run the executive branch, and are confirmed by the Senate. While they might not be elected offices, they’re clearly the next best thing and reflect the confidence of the elected president and the elected Senate.

Gerald Ford was sworn in as President in 1974 after Richard Nixon's resignation, a consequence of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyThis Is an Easy One, Congress

For these reasons, scholarly consensus has long held a dim view of the 1947 law, even among those who think it’s probably constitutional. The secretary of state or the secretary of defense are much more obvious and logical choices, along with other Cabinet officers in roughly descending order of importance (technically, the order in which their departments were created).

Congress should take up reform of presidential succession next year, building on the spirit of the bipartisan reform the Electoral Count Act, another obscure law that was mostly ignored until one day it suddenly mattered a lot.

There are also other aspects that could be tweaked, such as clarifying the place of acting Cabinet secretaries. Some have suggested adding officers at the end of the list who don’t primarily live and work in Washington, D.C., in case of a nuclear attack. But these are relatively minor concerns.

The most important fix Congress could make is dead simple: simply remove the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore from our list of potential back-up presidents. Hopefully, we’ll never have to worry about it, and all our future presidents and vice presidents will live long and healthy lives until they leave office after four or eight years.

But if we ever need it, the succession act should work at its one job. We should never be in a situation where two individuals are slugging it out, at best in the courts or at worst in the streets, for control of the nuclear codes. Congress should fix it before it’s too late.