Last month, the federal government won its case against Gary Winner, the CEO of Planned Eldercare, an Illinois medical-supply company. Winner had been charged following an intensive investigation which found that his company preyed on older patients by asking for their Medicare number in return for free medical devices.

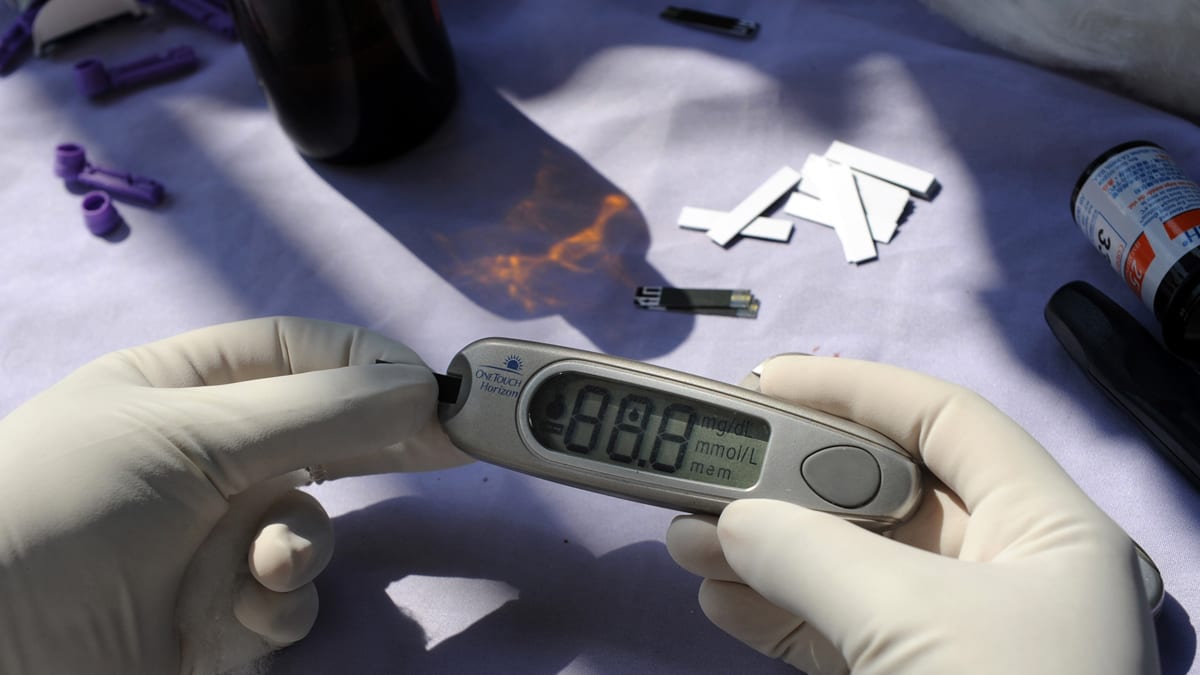

Many of Winner’s marks had diabetes, and he sent them what every diabetic needs: blood-testing strips and lancets, which they use to monitor their blood glucose levels—some of them several times a day. But Winner also threw in various ankle, knee, and elbow braces, and even erectile-dysfunction machines. According to court papers, Winner bought penis pumps from a California sex-toy shop, repackaged them and labeled them as medically necessary devices for diabetes to “help increase blood flow to the prostate.” Planned Eldercare then billed Medicaid at a 1000% markup, for a total of more than $370,000.

The prosecution of Winner, which resulted in a three-year-plus prison sentence for Medicare fraud, was a long time coming, but there is more that could be done to expose the darker corners of the multibillion-dollar business that is diabetic medical supplies.

Nearly 25 million Americans struggle with diabetes, and about 2 million are diagnosed with the life-threatening disease each year. The Centers for Disease Control reports diabetes is a major cause of heart disease and stroke, and the leading cause of kidney failure, new cases of blindness and a majority of limb amputations. In other words, it is not a disease to mess around with.

But that is happening every day, as uninsured diabetics, faced with the high cost of the blood-monitoring equipment, are increasingly turning to quasi-legal or outright illegal suppliers. At a pharmacy, a box of 100 small plastic blood-testing strips sells for about $125. On the Internet the price can be less than half that.

For example, a recent posting on Craigslist in Dallas, under the title “Contour Diabetes Test Strips,” offered “9 boxes ... unopened 50 strips per box. Asking $20 per box obo exp 6/2012”.

The posting, like most of its type, mentions nothing about how the seller got the boxes. The truth is that some are offered by family members of deceased diabetes patients, others by those who shoplifted the items from a store. Nationwide, entrepreneurs scout estate sales looking for abandoned supplies to resell online.

And even though no diabetic patient could possibly use 450 test strips by June, the demand for cut-rate supplies remains high, and the lack of significant federal regulation in the area makes it very difficult to stanch the supply. (Public health officials caution diabetics that the strips are sensitive to moisture and temperature, and are not reliable unless kept in a controlled environment and sold by a licensed pharmacist.)

In fact, the federal government itself may be an unwilling abettor to the fraud. Of the more than $1 billion that Medicare and Medicaid spend each year subsidizing purchases of test strips, at least $200 million of that is “unaccounted for,” according to a recent series of region reports by the Department of Health and Human Services. Privately, officials say that number is a very conservative estimate of the annual losses.

When asked to comment on what is being done to alleviate the fraud and waste connected to the supply of government-subsidized diabetic supplies the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

While test strips and lancets are both available over the counter, any seller of diabetic supplies must register with the Food and Drug Administration. Some online merchants, such as charitable organizations, have done so, but most have not. And no online sales are sanctioned by the biggest manufacturers—Johnson & Johnson’s LifeScan brand, Abbott, Bayer, Nipro, and Roche.

So where are all the underpriced diabetic supplies coming from?

Shirley Mendoza, for one. In 2004, Mendoza was working as an administrative assistant at a Roche lab in Berkley, Calif., and somehow convinced the home office in Indiana to send thousands of boxes of test strips to the lab, where she intercepted them. Prosecutors said Shirley sold the strips on eBay for a total of $1.5 million, then funneled the money through her husband’s bank account to buy eight expensive cars and three properties. After a joint investigation by the FDA and the FBI the Mendozas were arrested and charged with conspiracy, mail fraud, and money laundering. Charges against her husband were ultimately dropped, but Shirley pleaded guilty and was sentenced to just under three years in prison.

A much bigger problem than individual fraud is the glut of supplies, which drives the online black market.

Jerry Koblin, who runs a family pharmacy in Nyack, N.Y., says many of his customers complain that their auto-fill programs send far too many boxes of test strips. Online resellers are aware that the strips expire, of course, and constantly run newspaper and Internet ads screaming, “WE BUY TEST STRIPS! $20-$30 FAST CASH!” For diabetics with an oversupply of strips, it is a tempting offer, even though it is against the law to resell supplies subsidized by Medicare or Medicaid.

Koblin says lower-income diabetics also sometimes make the difficult decision to pay for groceries instead of medical supplies. “Some patients who are supposed to test themselves three times a day may only test once, or skip a day here and there,” Koblin explained. “The leftover strips add up quickly.”

But the government is beginning to take more concrete steps to combat the waste and fraud in the diabetic-supply industry. The HHS Office of Inspector General will shortly release a consumer-fraud alert urging millions of diabetics on Medicare and Medicaid to report if they believe they have been the target of fraudsters offering “free” supplies through cold calls.

There are also technological approaches to reducing the amount of graft in the diabetes supply chain.

In October, Atlanta-based ALR Technologies got FDA approval for a new cross-platform technology that could remotely tap in to any blood-glucose monitor and forward its information to doctors, insurers or even the government.

Currently each of the major diabetes-monitor manufacturers makes a slightly different model that only reads their branded test strips. The monitors themselves are often treated as loss leaders, given away to encourage patients to buy the strips. But as a result, data stored in one monitor cannot be transferred to another, and it is difficult to tell how many test strips a patient has legitimately used in the monitor each month. That data is crucial in determining how many the patient needs in the future.

“The technology is readily available,” said Sidney Chan, the chairman and CEO of ALR. Chan and others familiar with the challenges diabetics face see electronic verification of test-strip usage as the best first-step solution to a multimillion-dollar problem. “The reason why it is not being used is that it has not been required by Medicare.”

“Diabetes is the most costly of all the chronic diseases to treat,” Chan said. “If the test supplies are used properly the patient has control over the disease. If they aren’t used correctly all of us pay for the full complications of it.”