Our bodies weren’t meant for this world we’ve built. That’s why your back hurts. The things you think are normal are not. The world around you is an alien landscape, a science fiction movie set.

This is not the matrix. This is our everyday, modern life. But if you’ll take a step back with me, you might find that there is hardly anything ordinary about the world we’ve built. The very built-ness of our world is precisely what makes it so foreign to our bodies. In some ways the banal conveniences we seek out and enjoy are actually killing us by a thousand tiny cuts over decades and decades.

Of course, a thousand cuts over the course of a lifetime is a much better way to go than say, one big wound from a saber-toothed tiger taking a bite out of your head. Or finding yourself exposed with no shelter on a freezing tundra. We have eliminated some of the worst things that humans have experienced for most of our history on this planet. That’s quite the accomplishment. But we’ve traded these dangers for the perils of inactivity: heart disease, type II diabetes, some forms of cancer, back pain, joint pain, and possibly a smorgasbord of mental health issues.

Consider the kitchen counter. As you rinse your dishes, blend your smoothie, and grate your cheese, everything is within arms reach. At most you’ll take a few steps to the fridge, bending or squatting for a few seconds to put the bologna back in the crisper. (You fool! Bologna doesn’t go in the crisper!)

Contrast that with activities of daily life in say, rural Uganda. In Pajule, a small town where I spent a couple summers, it was typical for (mostly) women to get up before dawn to work in their fields planting, weeding, or harvesting. They’d carry water for the day’s chores and gather wood for the cook fire. The tasks of daily living were primarily performed on the ground—laundry, dishwashing, cooking dinner, or boiling water for tea. Children, adults, and the elderly moved throughout the day, squatting, carrying, walking, reaching, and bending at the hips.

These folks face plenty of hardships, but one thing they do not lack is movement. Those of us lucky enough to live in richer countries have managed to build and engineer movement out of our environment. That may make us comfortable in the short term, but this has serious consequences for our bodies.

I asked Daniel Lieberman, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University and author of the book The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health and Disease, about what our modern built environment is doing to us.

“We have to evaluate those costs and benefits,” Lieberman said. “So much of the world that we take for granted—the world around us—and think is normal, it isn’t normal. That doesn’t mean it’s bad, but it’s not normal from an evolutionary perspective.

“We all love comfort,” he continued. “If we were to distribute comfy chairs around the world, people around the world would sit in them. And comfort has its benefits for sure, but if your goal is long-term health, there’s plenty of evidence that not all the things that are comfortable are good for us. That doesn’t mean that everything comfortable is bad for us, of course.”

Lieberman pointed out that we didn’t necessarily evolve to be healthy—we evolved to have as many offspring as possible. From an evolutionary perspective, we only needed to live long enough to have some babies, and to make sure that those babies would survive long enough to have more babies. This means that many of the traits that made it into our genes aren’t aimed at our long-term self-interest, in terms of health.

“We didn‘t evolve to make the kinds of choices that we have today,” Lieberman told me. “And we’re asking people to make choices that they can’t make—most of us. If you put a brownie and an apple in front of me, of course I’m going to eat the brownie. We’re asking people to do things that are really, really challenging, and then shaming them and blaming them when they make the ‘wrong’ choice.”

But our evolutionary drive for acquiring cheap energy also makes us loath to unnecessarily spend it. In Lieberman’s book he points out that even today’s hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers will relax, when possible: “When hardworking people with limited food have the chance, the sensibly sit or lie, which costs much less energy than standing,” Lieberman writes.

But of course comparatively, we are not hardworking, nor do we have limited food. Quite the opposite. But it’s not just sitting—our natural desire for taking the path of least resistance plays out in every aspect of our lives.

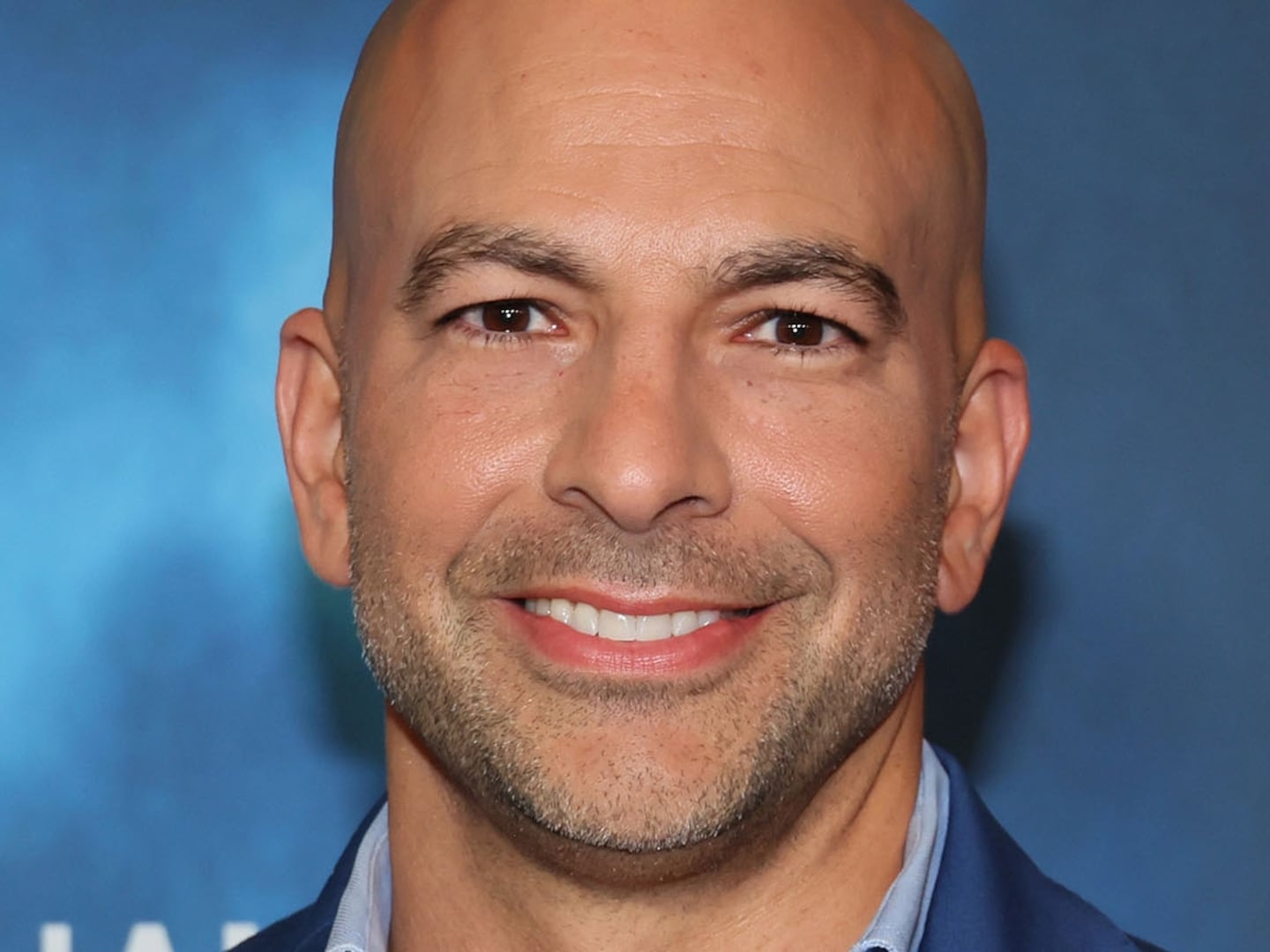

Andy Fosset is CEO and co-founder of GMB Fitness, a web-based company focusing on bodyweight exercises geared toward helping people gain “physical autonomy.” “Our built environment doesn’t allow us to do what should be natural movements,” Fosset told me. “We find ourselves interacting with chairs and doors and walkways, and as a result, we get used to bending only forwards. Almost never backwards, never to the side, we don’t really rotate our hips very much.

“So when things do happen that cause us to move that way, things that are unexpected, we find that our bodies are tight, and we end up either limited with a stiffness or an ache, or in pain, or in some situations, we can find ourselves injured,” Fosset said.

James Ivaska is a kinesiologist and owner of Muscular Health Center in Alexandria, Virginia. He specializes in treating soft-tissue pain and described to me the vicious cycle he sees play out among his clients whose injuries are often a result of not getting enough natural movement.

“We’ve built our environment to a point that moving is a rare event, when it really should be the majority of our day,“ he said. Sitting, for example, shortens muscles like the hip flexors, reduces blood flow, limits the range of motion, and leads to tightness, pain and injury. “Lack of movement creates pain and dysfunction. Pain and dysfunction hinder movement, and people are less likely to move because they can’t, or it hurts. That leads to more lack of movement and the cycle repeats.” Ivaska said.

Our bodies were built to move, but we’ve built a world where that just doesn’t happen. As a result, many of us find it difficult to perform the simplest actions.

“One of our most popular videos was one in which Jarlo [one of GMB’s co-founders] just messed around on the ground for about a minute standing up and sitting down without his hands,” Fosset told me.

“That was really interesting because being able to stand up and sit down is one of the indicators and aging, and not being able to do this simple task increases the risk of mortality.”

Pain and immobility affect millions of people, and they’re viewed as a normal part of life, but they don’t have to be. Of course, that doesn’t mean we all need to shed our shoes and chase down an antelope. None of the people I spoke with recommended everyone going “full paleo.”

“The solution isn’t to get rid of chairs or computers or dishwashers, they are important time savers and can be very useful to be more productive. But we do need to understand the consequences of those technologies,” Ivaska said. “I encourage my clients to move more, and move better, despite the environment we live in. Moving used to be a subconscious act because we had to move. Now it has to be a conscious act,” he said.

“I think any change in the direction of just moving more is better. You don’t have to take off your shirt and go climb a tree to get value. You just have to begin breaking out of that built environment a little bit, in small ways. Just because a chair is there doesn’t mean you can’t stand, or sit on the floor,” said Fosset.

“I think there’s a lot of benefit just to understanding [our evolutionary context],” said Lieberman. “I mean, I might still eat the brownie in front of me, but understanding what that brownie is, how my body digests it, how it affects me, and why I crave it—that’s all useful information. It might not change whether I eat it or not, but it’s valuable to question and understand what you do with your body.”

It’s valuable to understand that these are ancient bodies living in a brand new world.

“Noticing it is half the battle,” said Fosset. “Because it’s something that’s all around us, we’re steeped in it and we never notice it.”