Louisiana has done it. They have moved young people into one of the most notorious adult prisons in the United States.

In July, Gov. John Bel Edwards announced that two dozen young people from Bridge City Center for Youth—a juvenile corrections facility outside of New Orleans operated by the state’s Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ)—would be relocated to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola Prison.

Importantly, juvenile delinquency in Louisiana is determined through civil, not criminal proceedings. Young people who are adjudicated as delinquent and sentenced to confinement are supposed to receive “rehabilitation and individual treatment.” Gov. Bel Edwards’ plan to incarcerate children at Angola would subject these youths to conditions so threatening to their health and safety it constitutes punishment—not rehabilitation or treatment—and violates their constitutional rights.

This problem has heightened intensely, and now threatens the safety of every incarcerated young person in the state.

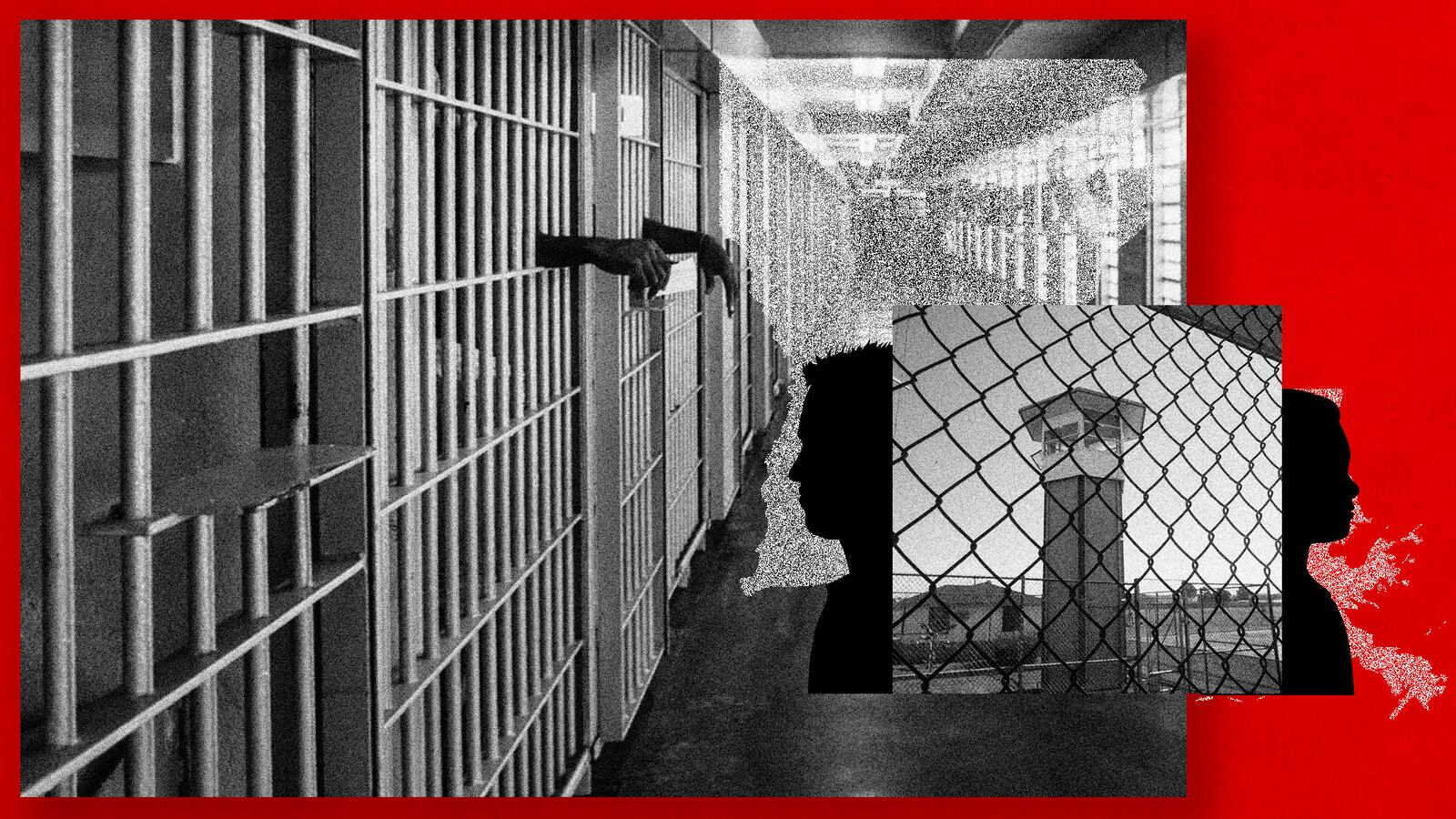

Built on the grounds of a former slave plantation, and with over 6,000 inmates, Angola is the largest adult maximum-security prison in the nation. There is a long, troubling history of lawlessness and abuse at Angola. And while there have been efforts to improve the prison over the years, abusive conditions have been documented through reports and court rulings for the past century, including brutal beatings by guards, denial of basic medical care and mental health care, assaults, and extensive use of solitary confinement.

A prisoner’s hands inside a punishment cell wing at Angola prison in Louisiana on Oct. 14, 2013.

Giles Clarke/GettySadly, the legacy of violence and at Angola today is pervasive throughout Louisiana’s penal system. After centuries of failed policies, state political leaders—including Gov. Bel Edwards, legal authorities, and law enforcement officials—are worsening problems for incarcerated individuals, their families, and our communities rather than repairing their harrowing results.

By addressing issues like understaffing and overcrowding in state juvenile facilities, Louisiana could avoid forcing incarcerated minors to Angola. Research from Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.aecf.org/blog/why-is-detention-reform-important__;!!LsXw!U6yyejY-7tULGZ5eXxOTEoPZfYW33GQHad4-8E68qrIiFP1BKpKqE9PI4PWnMML5U7Mi81H1OnAERtvrRxMbB_DveiBa2w$"> Research from Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, which operates in nearly 300 jurisdictions throughout the country, suggests that youth incarceration can be reduced without jeopardizing public safety.

For example, when public officials work with community leaders and families, we can reduce the number of young people in prisons)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.aecf.org/blog/jdais-deep-end-sites-safely-and-significantly-reduce-rates-of-youth-confine__;!!LsXw!U6yyejY-7tULGZ5eXxOTEoPZfYW33GQHad4-8E68qrIiFP1BKpKqE9PI4PWnMML5U7Mi81H1OnAERtvrRxMbB_C8sZEUow$">we can reduce the number of young people in prisons, while creating programs and services that meet the needs of troubled youths—including many with severe emotional or psychological issues. When jurisdictions reduce the number of youths in local and state custody, they can focus what limited resources they do have on a smaller number of young people who need more intensive mental health services, like counseling and remedial education.

In August 2022, Lawyers for Youth at Bridge City filed a federal lawsuit to prevent the transfer of any youth to Angola. A hearing before Chief District Judge Shelly Dick in early September revealed that any child in custody of the Office of Juvenile Justice in need of secure detention is at risk of being sent to Angola—not just youths from Bridge City.

On Sept. 23, the judge issued her ruling.

In a 64-page decision, the judge noted that putting a young person “in a locked cell behind razor wire surrounded by the swamps at Angola” is “disturbing” and “untenable,” particularly in view of the history of trauma and mental health problems of so many of the children in state custody. Judge Dick also stated that “the threat of harm” presented by some youths is “intolerable,” and concluded, “[t]he untenable must yield to the intolerable,” denying the motion to halt the relocation and clearing the way for the State to transfer incarcerated minors to Angola.

At the September hearing, while the judge called conditions in the juvenile cellblock “untenable, she was persuaded by the state’s promises to make “major” changes in the facility to allow the transfer. The state promised to create a new, completely separate, fully-staffed, fully-resourced youth facility on the grounds of Angola before it sent any young people there. The judge accepted those promises and incorporated them into her decision. As a result, she held that the planned site “has adequate physical facilities needed to temporarily house high-risk youth,” that “no youth will be transferred to [the facility] until the facility is ready, properly staffed, and can fully provide educational, medical, mental health, recreational, and food services.” Further, that the State will “eliminate” any contact with adult prisoners.

Looking through a fence at a guard tower inside Angola Prison.

Giles Clarke/GettyHowever, there is little indication that most of the supposed improvements Judge Dick’s ruling required will actually be implemented. As evidenced by the last several decades, Louisiana has not created any fully staffed, fully resourced youth facility, such as the one promised to Judge Dick.

The last time Louisiana opened a “temporary” youth facility, it was a disaster)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/03/10/no-light-no-nothing-inside-louisiana-s-harshest-juvenile-lockup__;!!LsXw!U6yyejY-7tULGZ5eXxOTEoPZfYW33GQHad4-8E68qrIiFP1BKpKqE9PI4PWnMML5U7Mi81H1OnAERtvrRxMbB_Bqn7V0fg$">it was a disaster.

To create the “Acadiana Center for Youth at St. Martinville,” the state leased a 24-bed jail from the St. Martin’s Parish Sheriff with individual cells, which differed from the dormitory-like setting in other OJJ juvenile facilities. When the youths arrived at St. Martinville, there was no educational program at all.

As one youth said: “No books, no paper, no pencils.” Young people spent most of the day in solitary confinement or their cells; when they were released for a short period, they were put into physical restraints. Months later, after extensive media coverage and public outcry over the abusive conditions, the state began providing some classes, but still less than required by state education laws.

Louisiana’s credibility is now in question.

How can the state construct a facility suitable for youth that it has not been able to create anywhere in the state over the past decade, in a matter of weeks or months—let alone inside the former death row unit at Angola? Why should we believe that more security will work to address the challenges in OJJ facilities when OJJ has been incapable of solving its problems for years? Why is the state willing to invest millions of dollars to improve poor conditions at Angola if the youth facility is to be “temporary”? Will Angola become another St. Martinville?

More than 40 percent)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/asp/Age_Sex.asp__;!!LsXw!U6yyejY-7tULGZ5eXxOTEoPZfYW33GQHad4-8E68qrIiFP1BKpKqE9PI4PWnMML5U7Mi81H1OnAERtvrRxMbB_AawQ-d1g$">More than 40 percent of the youths in state custody are charged with a non-violent offense, misdemeanor, or technical violation of the law. In many other states, young people are not sentenced to incarceration for these relatively low-risk offenses. Instead, they are placed in community-based supervision and treatment programs. If Louisiana could reduce the number of youths in its custody by 40 percent (or 20 percent, or even 10 percent), it could devote more resources to the small number of youths who truly need intensive interventions, and avoid sending youths to Angola.

While it’s vividly clear there are tangible solutions to help solve the issues faced at Bridge City, supported by quantitative data and decades of research, these solutions are falling on deaf ears to Louisiana state legislators, judges, and authorities. Instead, elected officials like Gov. Bel Edwards are resorting to needlessly punitive measures—like putting minors into a maximum security adult prison like Angola, exacerbating the already festering wounds within the state penal system and draining more resources from the state.

While I sincerely hope that no states follow Louisiana’s lead—and that elected officials throughout the nation take note of Gov. Bel Edwards’ negligence and mismanagement of Louisiana’s penal system—it’s the children of Bridge City’s Center for Youth who are paying the ultimate price. The burden of ensuring the state is held accountable is now on parents, advocates, and attorneys for youth who will be transferred to Angola.

Their health, safety, and well-being are in imminent danger.