Quentin Tarantino probably feels like his beleaguered Bride from Kill Bill this week, with the combination of Uma Thurman's New York Times interview about the accident she was forced to endure on one of his film sets and the resurfacing of his Howard Stern interview where he defended Roman Polanski's rape of 13-year-old Samantha Geimer in 1977. It makes you wonder: as more about Tarantino's past, his cavalier attitude toward statutory rape, and his behavior toward the actresses in his films comes to light, should we re-examine the films of his that have been dubbed feminist?

Tarantino has expressed regret for his comments about Geimer from 2003. Of the rape, Tarantino said, "He didn’t rape a 13-year-old. It was statutory rape. That’s not quite the same thing. … He had sex with a minor. That’s not rape. To me, when you use the word ‘rape,’ you’re talking about violent, throwing them down; it’s like one of the most violent crimes in the world. Throwing the word ‘rape’ around is like throwing the word ‘racist’ around. It doesn’t apply to everything that people use it for. He was guilty of having sex with a minor.”

He continued to insist that the sex was consensual and that Geimer was a "party girl" who "wanted it." Geimer has since refuted the claim.

“[Polanski] had sex with a minor. That’s not rape. To me, when you use the word rape, you’re talking about violent, throwing them down—it’s like one of the most violent crimes in the world,” he told Stern. This week, Tarantino issued an apology. "When Howard brought up Polanski, I incorrectly played devil’s advocate in the debate for the sake of being provocative,” he said in a statement. “I didn’t take Ms. Geimer’s feelings into consideration and for that I am truly sorry.”

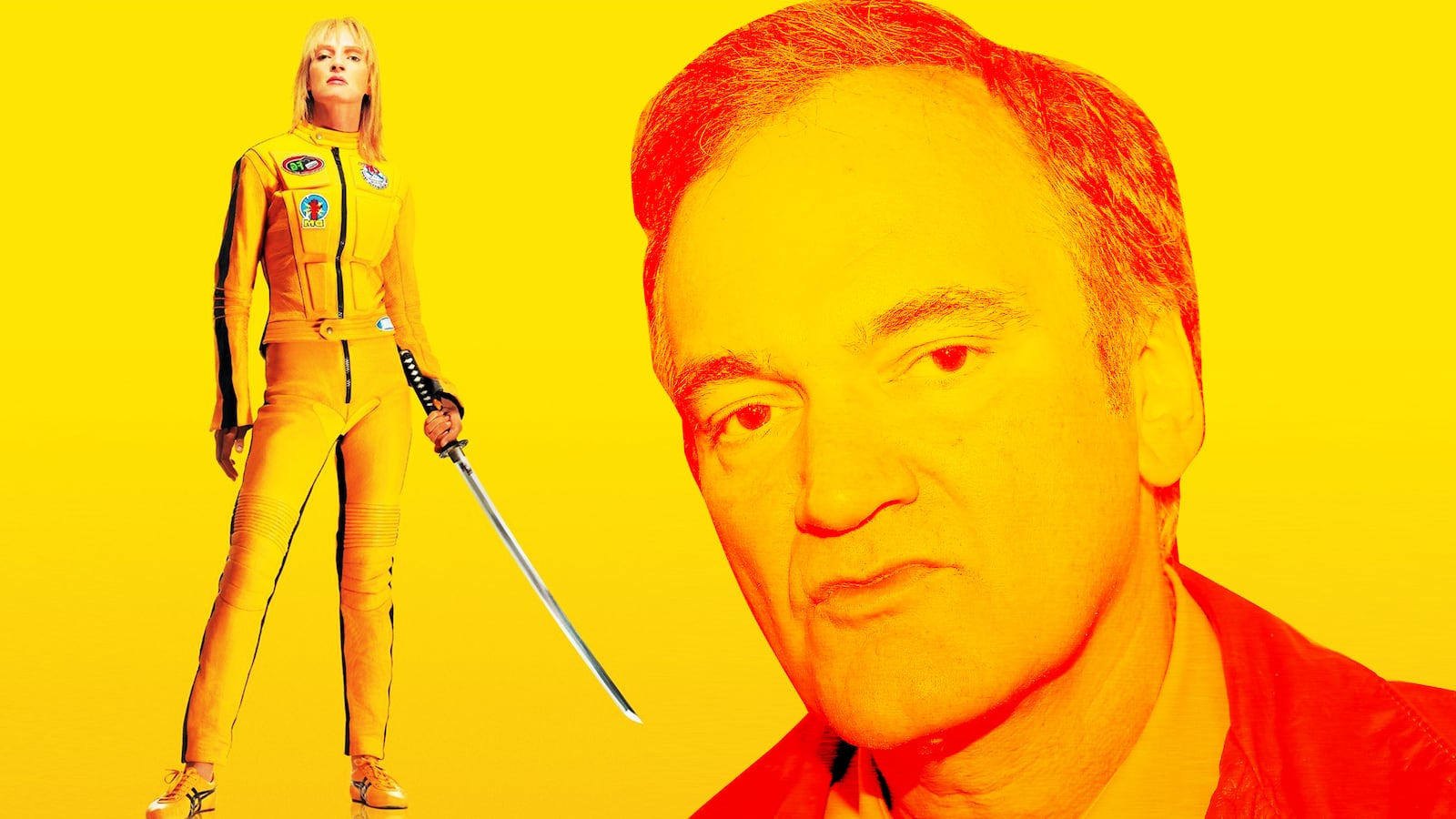

Apologies aside, the exchange calls into question what Tarantino personally does and does not perceive to be rape. The interview took place in 2003, long after his film Kill Bill, where protagonist Thurman is put into a coma by her former assassin squad and is subjected to rape while she's unconscious in a hospital. Kill Bill has often been branded a feminist film because of the Bride's strength in taking down her enemies and the multiple roles it offers for women to be murderous badasses. But there's also the idea that to become triumphant, the Bride needs to be raped, beaten, and broken down.

Thurman herself was subject to abuse on set under the guise of auteur filmmaking. In her New York Times interview, Thurman revealed she was coaxed into a life-threatening car stunt on the set of Kill Bill that resulted in an accident. The car crashed into a palm tree, resulting in concussion and knee damage. Thurman said of the incident, "The steering wheel was at my belly and my legs were jammed under me. I felt this searing pain and thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m never going to walk again’…When I came back from the hospital in a neck brace with my knees damaged and a large massive egg on my head and a concussion, I wanted to see the car and I was very upset. Quentin and I had an enormous fight, and I accused him of trying to kill me. And he was very angry at that, I guess understandably, because he didn’t feel he had tried to kill me.”

She went on to describe actually being choked with a chain during a fight scene and Tarantino spitting on her face during a scene as well, so that it would look the way he wanted it to on camera. Can a film then be feminist when it fetishes the abuse of its heroine and also exacts abuse on her during the making of the film? Contrast that with Django Unchained, where Jamie Foxx portrays a runaway slave who takes revenge on southern slaveowners. Foxx's character is largely spared the abuse of slavery; we don't see the trauma on him often. It is instead shown through two slaves who are forced into a fighting match and through Kerry Washington's character. It's the torment of his female lover that pushes Foxx into triumph.

It's this type of behavior that colors critical analysis of Tarantino's films. For instance, lost among his comments about how we use "rape" incorrectly and how it only applies to a violent type of assault, he also says in the same interview that "racist" is a word we throw around too much. Presumably because Tarantino loves to use the n-word in his scripts and he's been called out on it. Does his cavalier use of the word and the casting of actors like Foxx, Samuel L. Jackson, and Pam Grier in strong roles counteract the lurid use of that racial slur? Not really. Nor does the fact that there is an onslaught of abuse heaped on many of Tarantino's allegedly feminist characters. Most recently, Jennifer Jason Leigh's so-called great villainess in Hateful Eight became the punching bag for an all-male cast. Is that progress? Just because she can tote a gun, toss out the n-word, and look like a badass occasionally?

Perhaps then it's time to analyze films like these as triumphs not of a director, but of the actresses who star in them. If Kill Bill can be seen as a feminist film now, it's because Thurman managed to survive abuse from Harvey Weinstein and Tarantino and still come out the other side triumphant. She's shared her story and attempted to cleanse the demons of a film that now means more than it did when it was a grindhouse-inspired midnight viewing cult classic. Kill Bill is that much more powerful because of Thurman's truth. Tarantino just happened to catch it on camera.