Last week, Tony Martinez, the Mayor of Brownsville, Texas, described the difficulty of reuniting immigrant families separated at the U.S.-Mexico border as a “Herculean task.” Sadly America’s long history of breaking up minority families provides ample proof of the lasting damage likely to be wrought by the Trump administration’s inhumane policy.

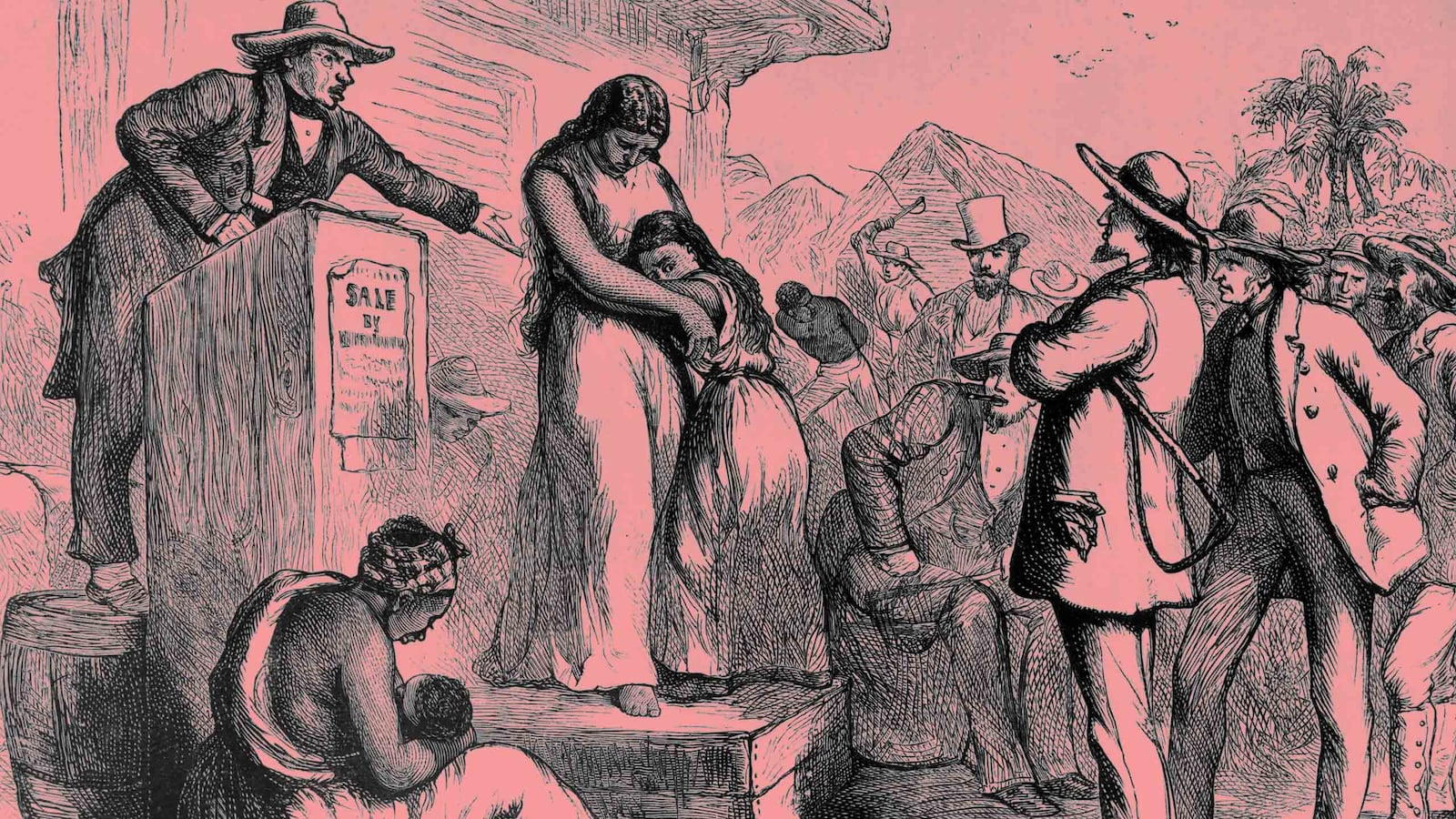

For as long as slavery existed in America, our nation’s domestic slave trade broke up black families, yet the stories of these traumatic separations are not widely known. Despite losing the Civil War, the South still suppressed black voices via Black Codes and Jim Crow, and only since the 1960s have the first-hand accounts of family separation in the black community become more mainstream.

After the Civil War, thousands of newly freed African Americans placed “Information Wanted” ads in black newspapers across the South in search of family members.

“Information Wanted, Of Racheal, a young Mulatto Woman, who was sold in this city in the Spring of 1864, to Mr.--- Moore by Mrs. Mary Ann Baldwin, of Mississippi. Information of her whereabouts, left with us will be thankfully received by her father,” reads an ad in the Montgomery Advertiser on Aug. 25, 1865, only four months after the end of the Civil War.

In 2017, Villanova University’s Department of History launched Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery and in less than two years the department’s researchers have found over 3,000 Information Wanted ads.

Some of the oldest ads in their collection date to before the Civil War. These ads appeared in the North and in Western free states. Abolitionist newspapers that ran these ads challenged America’s fugitive slave acts, which demanded that escaped slaves must be returned to their Southern slave owners.

“When newspapers helped runaway slaves take out these ads, they did so at their own peril,” said Judith Giesberg, Villanova University history professor and director of the Last Seen project, to The Daily Beast.

In 1847, Louis Clark, who escaped slavery in Georgia and found freedom with the Choctaw Nation in present-day Oklahoma, placed an ad in the Fort Worth Gazette in search of his brother Lee and sister Clarica, who were sold to Henry Ware from Alabama and taken to Texas.

The Last Seen’s most recent ads are well into the 20th century. In 1917, James E. Johnson of Jamaica, New York, posted an ad searching for his father, mother, two brothers, and his sister who were sold in 1861 in New Kent County, Virginia, when he was only 10 years old. Johnson had not seen his family in nearly 60 years, and there is no indication that they were ever reunited.

“For those who have been shaking their heads and saying that what is happening on the U.S. border is not American, they need only to look at this collection to be reminded that it is very American,” said Giesberg. “We’ve been doing things like this since this country was founded.”

And what, you might be wondering, about family reunification? Giesberg says that her collection has fewer than 100 ads describing a reunification. “About one-third of enslaved children in the upper South experienced separation either by being sold themselves or from losing a mother, a father, or siblings,” said Heather Andrea Williams, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery, to The Daily Beast.

For her book, Williams found more than 1,200 Information Wanted ads. Her research also incorporated letters from black Americans hoping to find a lost loved one, and interviews and diaries describing the devastation of family separation.

In one letter an enslaved woman wrote to the wife of her former owner asking if she knew where her daughter had been sold because her current owner said that he would buy her daughter if she could find her. It is unclear whether the slave owner wrote back.

Other research describes children unable to eat or stop crying following separation, and how slave owners would fool young children into leaving their families. “Sometimes [the slave owners] give them candy. They try to placate them, and the kids don’t realize for a couple of days that they are not going to see their mother again,” said Williams.

One entry describes a child who would for years always return to the field where she last saw her mother and stare up at the sky hoping that the heavens would bring her back.

Information Wanted ads, letters, and slave narratives detail the trauma of family separation, and its impact that lasted for generations. Into the Great Depression and throughout Jim Crow, black families continued to speak about the devastating impact of family separations that happened roughly a century ago. The descendants of the formerly enslaved still felt the pain of separation.

Of course, today’s policy isn’t slavery, which was a unique evil. Still, in only two months, the Trump administration has already separated 2,500 children from their parents, and just over 500 have been reunited. And following President Trump’s latest order children will only be reunited with their family once their parents’ deportation proceedings are completed. Immigration cases can take up to two years to get resolved, however Trump’s recent tweets indicate a desire to disregard due process for these immigrant families.

Also, under current policy the onus rests on the parents to find their children, and the Trump administration appears to have not created a new plan to assist with reunification.

The carelessness and indifference shown by this administration will reduce the chances of family reunification, and it demonstrates a disregard for human life that is far more American than we like to accept.

“I think we need to be more honest about who we are, and stop trying to be so innocent,” said Williams. America’s Herculean task extends beyond family reunification and must incorporate taking an honest look at our history to ensure that we no longer repeat this inhumanity, no matter the scale.