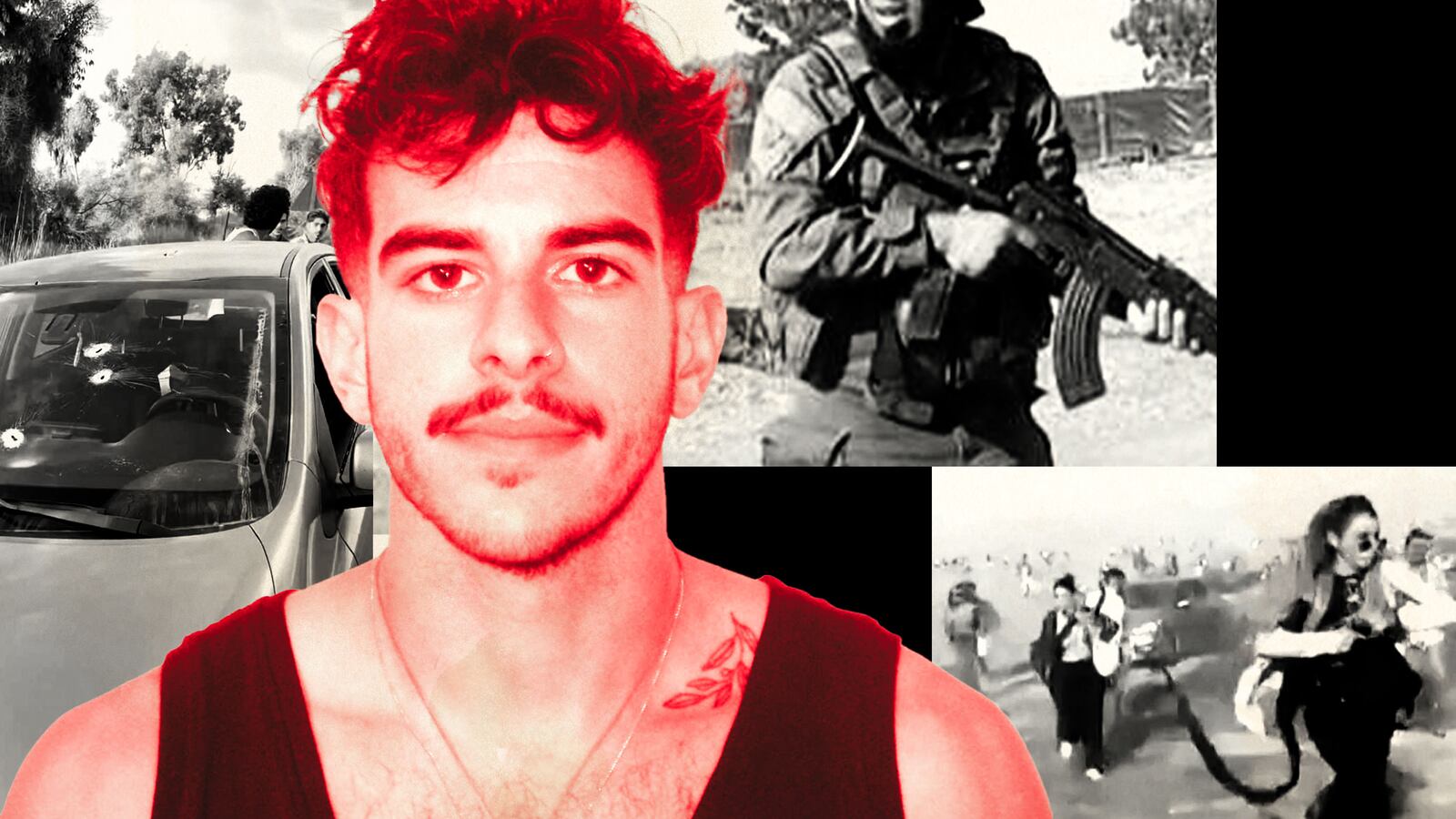

As told to the author, this is a first person account by Ido Sinvani, a 22-year-old survivor of the massacre that Hamas terrorists unleashed on civilians at the Nova Music Festival in Re’im, Israel.

Last Friday afternoon, my friends Yovel, his brother, Ofir, and their friend, Shimon picked me up from Ein Hod, a small artist village near Haifa where my mom lives, and we drove four to five hours South to Re’im to attend the Nova music festival.

Yovel, an artist invited to exhibit his work there, got us all in for free. We just needed to get there early to set up his pop-up gallery. Around midnight, the gates opened and the first DJ hit the stage. As the beats pumped, we drank Arak [an anise-flavored spirit] with lemonade and added energy powder to keep us dancing all night. Once the sun began to rise, we decided to refuel and left the rave to grab breakfast. We were determined to party until the festival ended at 3 p.m.

But as we returned at 6 a.m., we saw rockets launched over our heads and the music suddenly stopped. Then we heard the sirens, which are called Tzeva Adom, or “red color.”

You’re supposed to run for cover, but where do you hide in an open desert? Everyone looked confused, then people started to lay on the ground. There were 3,000 revelers just laying there silent and waiting. After about half an hour, the security guards yelled: “Yalla! Get up, get in your car and go!”

So we hurried to pick up the art, pack our car and drive off, but the first exit we tried was blocked. We quickly switched directions and tried a different route. Once we got to the main road, we found traffic had completely stopped. We parked by the side of the road and headed out to see what was going on. Within seconds, we realized we were sitting ducks. Cars were speeding toward us with bullet holes as bloodied passengers jumped out doors and windows, screaming, “Terrorists, terrorists! I was shot, run away!”

We ditched the car and ran.

From left to Right, Ofir Nimni, Ido and Yovel near their bullet-strewn car

HandoutBy now, it was probably around 7 a.m. Everybody was running in a panic and not knowing where to go. I looked up. There was a paraglider. Was this some random guy? Then I saw others, but figured the Iron Dome would protect us.

Then I heard the roar of pickup trucks and motorbikes as terrorists descended upon us from all sides, chasing us across the field and firing at us with long-range semi-automatic rifles. I heard the deafening pop of gunshots all around me as people next to me fell to the ground, dying, bleeding, screaming hysterically for help.

I saw the terrorists circling back to pick up the wounded and loading them on their trucks. I vowed I wouldn’t be their prey. Everyone began running in one direction, only to be caught in their crosshairs. My friends and I bolted the other way and kept running.

Being from the North, I’m not so familiar with this region, but I know my way around rugged terrain from my army training. We looked for a low-lying creek where if a bomb blew up or shots were being fired, they wouldn't ricochet off a surface and hit us. We found a bush and hid inside, removing jewelry, sunglasses and anything bright or reflective, camouflaging ourselves with dirt, branches and leaves.

Yoval and Ido

HandoutAs we lay there, huddled together, we said our goodbyes, trying not to sob. We figured this was it: we’re either going to die here or worse, get kidnapped. Yovel, Ofir, and Shimon said prayers, but I’m not religious, so I didn’t.

After three hours, all our phones died, except for mine. I had charged it in the car and had 10 percent of battery left. From our perch, we could see the terrorists, but they couldn’t see us. They were dragging bodies and hunting for more people to kill. And here we were, inches away, trying not to let out a peep. We covered each other’s mouths because we were screaming inside.

A few hours later, they moved on. I retrieved my phone and replied to as many texts as I could, assuring my mom I was OK and on my way back home. It was a lie. I just didn’t want her to know how dire things were. Would I ever see her or my brother again? I was beginning to doubt it.

With the battery nearly all gone, I sent one last text—my GPS location to a friend in the military, who said he would move it through the system to get us rescued. Then my phone died.

We were stuck, disconnected, wondering if or when we’d be saved, listening to the boom of nearby explosions and the relentless drill of gunshots fired at a rapid pace, while our attackers chanted “Allahu Akbar!” [God is Great] and in Arabic, “Kill all the Jews!” “Rape all their women!”

I saw them beating guys until they fell limp, and grabbing girls whose screams still ring in my ears.

By around 3 p.m., drained and dehydrated, Shimon and I decided to venture back to the car some 400 meters away to get us water and charge our phones. The area was now silent, so we felt it would be OK.

As we headed back, ducking low to the ground, we saw smoke rising from the road. It was full of bombed out cars, some so badly charred, all that was left was the outer shell. The path we had initially taken, before veering away and running to the creek, was now strewn with blood and bullet-ridden corpses. By the time we reached the main stage of what had been the festival, we could barely inhale.

The stench of hundreds of bodies is a smell I’ll never forget. Corpses were scattered everywhere, completely obscuring the stage floor. Some were burnt, others had limbs torn off, still others were beheaded, and some were still on fire. Nothing prepares you for something like this.

A dead woman lay, stripped naked, dried blood staining her inner thighs, daring me to look away. When I did, I noticed terrorists a few meters away, snapping pictures, recording videos and livestreaming the scene from their phones, as they gleefully shouted: “Allahu Akbar!”

Shimon and I looked at each other and just sprinted, not giving a fuck if they shot at us. I stumbled a few times, falling on cacti, breathless, and delirious.

I saw a black jeep crossing the bridge above us and thought it could be an IDF vehicle. But I realized Hamas had stolen it. They were everywhere.

I made peace with the fact I was going to die.

Hamas gunmen killed approximately 270 people attending an outdoor rave music festival in an Israeli community near Gaza.

Jack Guez/AFP via Getty ImagesBy the time we returned to the others, I was completely numb. I didn’t feel the blood and bruises on my knees and elbows. I didn’t mind feeling parched. Maybe I was dead already. They sobbed as I recounted what we saw, but I couldn’t. Crying usually comes easily for me, but I haven’t been able to shed a tear ever since that moment under the bridge.

By around 4 p.m. or 5 p.m.—honestly I have no idea—we heard people nearby. They were dressed in police uniforms, but I thought for sure they were terrorists.

Then I heard Hebrew spoken without any discernible Arabic accent. We emerged from the bush, shouting “Help! We’re here.” They escorted us out, guns pointed in all directions.

One of them stood out. His name is Tomer. He was positive and kept talking, telling us about himself, how his child was born a few days ago and that he was set to celebrate the birth the next day. But when he heard what happened, he sprung into action. He was wearing the vest of a fallen officer, because he arrived as fast as he could, neglecting to pack his gun or uniform. They put us inside the trunk of their truck as an extra safety measure, and we drove, hoping to find other survivors, but all we encountered was a trail of blood, bodies, bags and skeletons of cars, along with that terrible stink of burnt flesh, metal, and plastic.

Was I living through “Zombie Apocalypse” or was this horror real? With no sleep, little water or food and my adrenaline pushed to its limit, it was getting hard to tell.

Eventually we found eight other survivors and started sharing our stories. Everyone was crying, but me. I was in shock.

I got home around 11 p.m. and collapsed in my mother and brother’s arms. We hugged for a long time, and they cried.

“I love you. I’m hungry, I want to eat and take a shower.” That was all I could say.

After I did, I went to bed, but was awoken by nightmares of the scenes I witnessed. I still imagine guns being fired when there’s nothing around; loud and sudden noise makes me jump, and from the corner of my eyes, I think there are people hiding.

I had my first therapy session, but I don’t feel anything yet. For now, I’m just trying to process it and be here for my mother.

I don’t have a big message, I’m not there yet. But my sense of safety in Israel and trust in our Palestinian and Arab neighbors has been shattered. My brother has been called up to serve, and my mom is worried all over again. Every day, as more names and faces are brought to light, I recognize more friends who are dead or missing.

Ido and his mother, Yarra Shaltiel

HandoutI keep in touch with Yovel, Ofir, and Shimon on a daily basis. But I’m still detached from my emotions.

Right before you called, the siren rang. My mom shouted: “Come to the basement!”

“I don’t care,” I told her, “I’m going to eat, I’m not going to hide.”

If I die, I’ve made my peace. I don’t know how to describe what’s going on inside and outside of me. I’m trying my best. Yovel told me a nice thing the other day. He said we now have a second birthday—the anniversary of our survival. As time passes, I hope we can celebrate it.