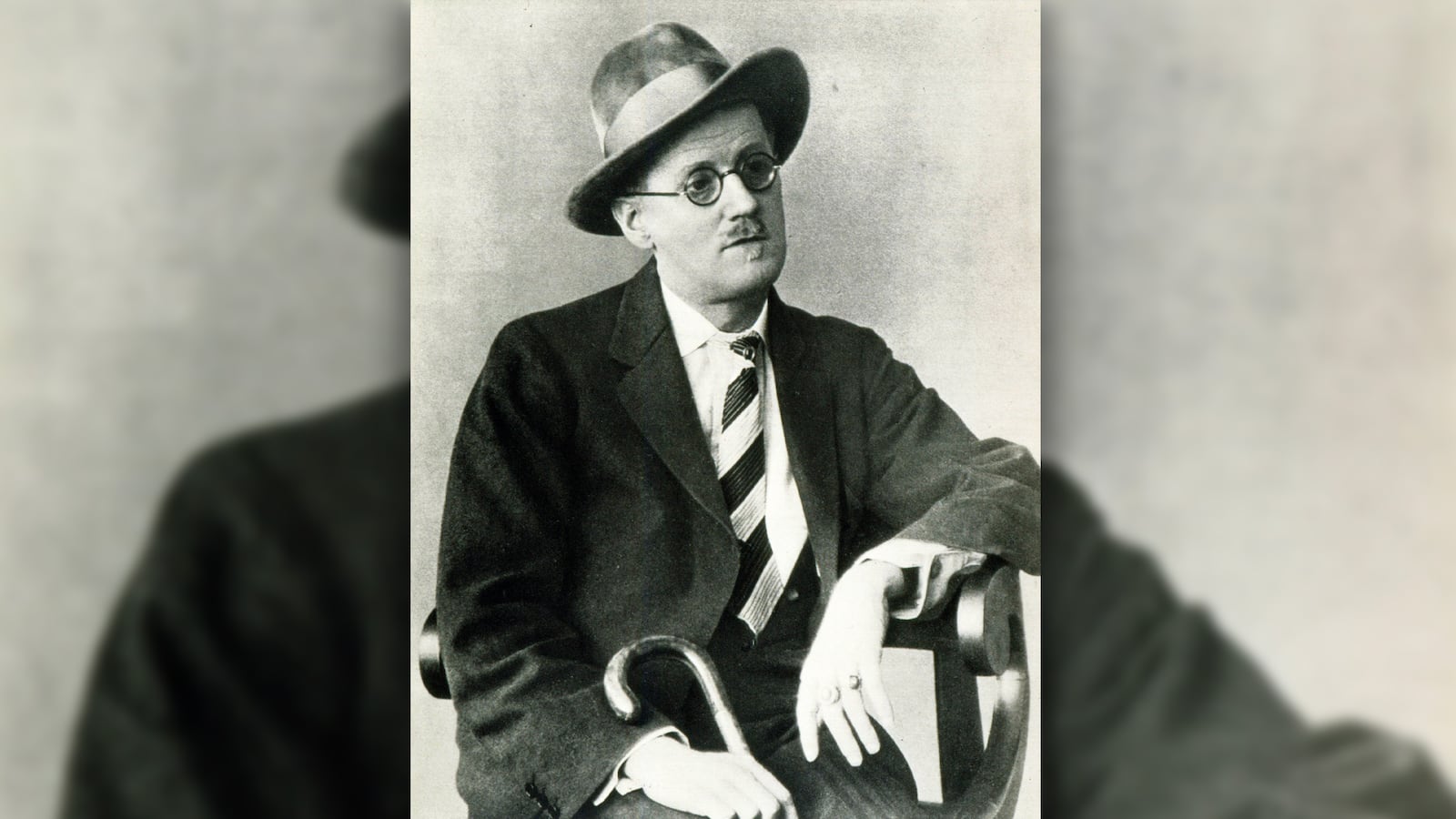

James Joyce was 25 years old when he wrote the greatest of all Christmas stories, The Dead, in 1907. His major works—Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake—were still ahead of him.

John Huston was 80 years old when he made the greatest of all Christmas movies, released in 1987. Huston’s most famous works—The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Asphalt Jungle—were in the distant past. The Dead would be his last film.

A self-imposed and impoverished exile, Joyce wrote The Dead and the rest of the stories in Dubliners in a dingy apartment in Trieste, Italy; Huston was an émigré to Joyce’s native Ireland, where, directing from a wheelchair, he shot some of the film’s exteriors. (The interiors were done in a warehouse in Valencia, Calif.) The circumstances under which the youthful Irish writer and the aging American filmmaker worked couldn’t have been more dissimilar. Their sensibilities, though, were simpatico. Joyce wrote with a feel for the cinematic, and Huston regarded his films of literary works—The Maltese Falcon, The Red Badge of Courage, Moby Dick, and Wise Blood—as companions to the original texts.

Joyce’s best biographer, Richard Ellman, called The Dead “a linchpin in Joyce’s work.” The author awarded his central character, Gabriel Conroy, several details from his own life: Conroy reviewed books for the pro-British Dublin Daily Express, taught in college, became Europeanized, and was mostly indifferent to the nationalist aims of the Irish. One important difference between the character and creator: On paper, Conroy returned to Ireland, a journey Joyce would never make, to give an after-dinner speech at a gathering to honor his two spinster aunts and their spinster niece, all music teachers—“The three graces of the Dublin musical world.”

The pages of The Dead are soaked in music, from reverential discussions of famous opera singers, long dead, to echoes of dimly remembered but still strongly felt folk songs. Joyce took his title from one of Thomas Moore’s Irish airs, and the song around which the story turns, “The Lass of Aughrim,” predates even Moore. D’Arcy, a tenor and friend to the family, sings the song as Conroy and his wife, Gretta (modeled on Joyce’s wife, Nora), leave the gathering on the night of Jan. 6, the Feast of the Epiphany—the last of the 12 days of Christmas. Hearing the song, Gretta withdraws into a reflective shell that baffles her husband.

Back in their hotel room, a curious Gabriel probes delicately to discover the cause of Gretta’s sorrow. He finds that the song was once sung to Gretta by a tubercular young boy who was in love with her in the wild country near Galway where she grew up. One night, in a cold rain, he came to Gretta’s window to serenade her with “The Lass of Aughrim,” caught pneumonia, and, a short time later, died.

Gabriel is stunned to find that Gretta has a past he knew nothing of. “I think he died for me,” she tells him.

A lesser writer would have given us a neat, gift-wrapped life lesson in which the boy’s death functions as an opportunity for Gabriel’s and Gretta’s personal growth. Joyce wants much more: a revelation. Gabriel has an epiphany of sorts—on the Feast of the Epiphany—but it is unsettling. He is jealous, though it’s not clear whether of his wife’s young, dead lover or the intensity of the boy’s devotion. In one of the story’s most oft-quoted sentences, the narrator tells us, “He had never felt like that himself towards any woman, but he knew that such a feeling must be love.”

For reasons he doesn’t understand, Gabriel fights back tears: “His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead… His own identity was fading out into a grey palpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling.” A few lines later, at the story’s close, “His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

Huston’s camera lingers over all Joyce’s major themes: the charm of Irish hospitality, the emotional power of old songs, the hold that the dead continue to have over the living. For Huston, the film was very much a family affair; his son, Tony, wrote the screenplay, which was nominated for an Academy Award, and his daughter, Anjelica, played Gretta. Like the characters in his movie, Huston was becoming a shade. Dying, he clung tenaciously to the task of completing a film whose defining moment is a character’s awareness of his own mortality.

From the Irish harp that plays over the opening credits to the heart-rending recitation of the song that brings Gretta to tears, sung by classic Irish tenor Frank Patterson, Huston shows what the medium can do to enhance the enjoyment of a great literary work.