Long before COVID-19 and years before the Spanish flu, typhoid fever ravaged New York and other cities around the world in a series of epidemics in the early 1900s, teaching lessons still crucial in today’s pandemic.

Like, how stupid do people have to be to repudiate life-saving strategies?

Then, as now, many cases went unrecorded, coming to light only when a victim turned up dead, and then, as now, the foolhardy flouted wise safeguards.

Today they’re protesting stay-at-home orders, and at least 12 states have rushed to reopen for business. Back then, after the Health Department traced a 1913 typhoid outbreak in a section of Manhattan east of Third Avenue between 6th Street and 33rd Street to a single milk company, health inspectors offered residents the same vaccinations successfully administered to the Army, where the typhoid rate among soldiers dropped from 3.03 per thousand in 1909 to 0.3 in 1912, a 99 percent reduction.

But as The New York Times reported on Sept. 19, 1913, “The east siders, however, were not eager to take advantage of the proffered immunization, even when informed they were exposed to danger.”

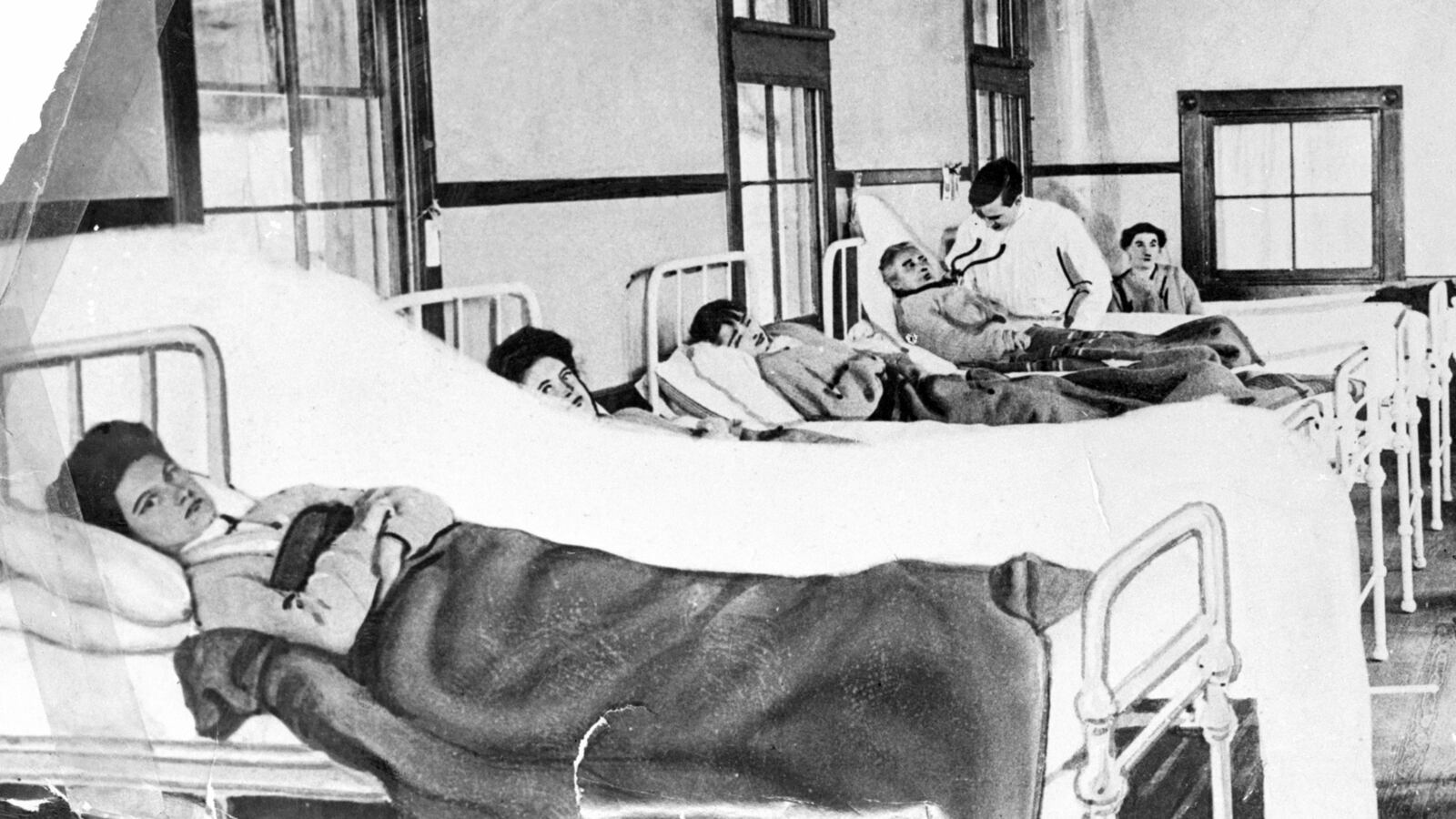

An often deadly infection of the intestines, typhoid fever is caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi in feces and urine that often contaminated milk and water supplies before the days of proper sanitation. Not to be confused with typhus, transmitted by a flea bite, typhoid attacked the blood and internal organs, causing diarrhea, high fever, fatigue and delirium, with victims often suffering a rosy body rash.

Sometimes, it was spread by healthy carriers like the cook Mary Mallon—better known today as Typhoid Mary—who infected dozens of New Yorkers (numbers vary), killing several. By World War I, typhoid was sickening some 300,000 Americans annually, killing 20,000 of them.

By comparison, so far, in less than three months, more than 1.15 million Americans have contracted COVID-19 with more than 66,000 deaths, including more than 13,000 in New York City. Worldwide, the toll stands at more than 3.4 million people sickened with almost 250,000 deaths.

Typhoid fever still afflicts 11 million to 21 million people annually around the world, killing up to 161,000, according to World Health Organization estimates.

The tale of typhoid’s havoc and government’s response in turn-of-the-century New York emerges in the files of the Bureau of Municipal Research, a relentless civic watchdog and investigator of government functioning, hired, and often imitated, by localities around the country.

Founded in 1906 by anti-Tammany reformers backed by wealthy philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller Jr., and E. H. Harriman, the bureau burst on the scene with an exposé of patronage abuses that claimed the scalp of Manhattan Borough President John F. Ahearn. By 1911 it established the first Training School for Public Service, which enrolled the future power broker Robert Moses and the later mastermind of public administration and New York’s first City Administrator, Luther Halsey Gulick III.

That same year, the bureau sought to investigate an alarming spike in typhoid cases that would sicken at least 1,133 New Yorkers from May through November, many, it would emerge, from a single unclean dairy on the west side.

Unlike COVID-19, the disease was no newcomer, with epidemics going back to the previous century. In 1897, British and German researchers had developed a vaccine that proved effective during the Boer War but gained only mixed acceptance, with nurses at the Mount Sinai Hospital and Nursing School refusing to voluntarily receive typhoid vaccinations, according to a May 27, 1913, Times article. They were ordered to comply.

As with COVID-19, whose spread has been linked to a single nursing home in Washington state, the Life Care Center in Kirkland outside Seattle, the 1911 outbreak in New York was preceded by a flurry of cases in the fruit-growing Washington city of Yakima, although, unlike with the coronavirus, there seemed to be no connection between the events. In Yakima, an investigating doctor, Leslie Lumsden, found “grossly unsanitary” conditions, including about a thousand filthy privies and cesspools, and inches of dead flies on a filter at a milk-bottling plant.

Meanwhile in New York, when the Bureau of Municipal Research requested Health Department records to study the city’s response to the 1911 typhoid outbreak, “it met with a flat refusal.” Bureau investigators won a State Supreme Court order to compel the information but the city appealed, overturning the judgment in the Appellate Division which ruled the bureau “shows no interest, legitimate or otherwise” in examining the records.

It was not until two years later, and a second outbreak in 1913 that sickened an additional 948 people, that the city’s Central Council of Public Health issued a report on the official response, finding little to quarrel with and seizing on tainted milk as the likely culprit.

“The Department of Health has used its present small force of typhoid investigators to good advantage,” the council found, while acknowledging that New York’s 1910 death rate from typhoid—11.6 per 100,000 population—was far higher than Hamburg’s (2.5), Berlin’s (3.6), London’s (4) or Paris’s (6.7). On the other hand, New York emerged better than Chicago (13.7), Philadelphia (17.4) or Washington D.C. (23.2). The chairman of the citizens professional advisory council was John Houston Finley who had just completed 10 years as president of the City College of New York and was later to become associate editor and then briefly editor in chief of The New York Times.

But the council’s report gave the Bureau of Municipal Research a new opening—to investigate the investigation, which it found sorely lacking.

“SAY TYPHOID CASES ARE MISMANAGED,” headlined The Times on Feb. 2, 1914, reporting on the bureau’s critical findings. Below that, sub-headlines that mirror those of today declared that “MANY WERE NOT REPORTED” and that “If 1911 Epidemic Had Been Properly Handled, It Would Not Have Recurred in 1913, Bureau Says.”

In a dense 71-page report, the bureau had faulted official reporting of cases as haphazard and scored the “inadequacy” of Health Department educational efforts and inoculations, which inspectors were supposed to offer all exposed people they encountered.

Had their investigators gained initial access to the requested records, the bureau wrote, their inquiry “would have prevented sickness and death in 1911, 1912 and 1913.”

Of the 948 typhoid cases reported in 1913, it said, over 200 were not investigated for six to 10 days, and 399 cases bore no record of when they were investigated at all. In 59 cases, the first indication of illness was when a victim turned up dead. Inspectors who had failed to report cases or fudged their hours on duty were not disciplined. Time sheets were fictive. The city undertook no efforts to enlist police officers or settlement workers to help report typhoid cases. And officials knew of a contaminated milk supply implicated in the 1911 outbreak for two weeks before acting to shut it down.

“The defective methods employed by the department in obtaining information as to cases of typhoid have been condemned so many times and by so many investigators that it might seem hardly worth while to comment on them in this report,” the bureau said.

“The lesson of 1911 was badly learned,” it said. In the face of the sudden recurrence in 1913, doctors and the public were misled by “garbled, misleading and often erroneous reports” and little effort was made to rally their cooperation.

The New York Tribune of July 17, 1911 said that health officials had attributed a sharp rise in typhoid cases to a long drought followed by heavy rains. The same day, inspectors traced 39 cases to bad milk from the Thorndale supplier between 26th and 110th Streets on the West Side. Later Health Commissioner Ernst J. Lederle denied any epidemic and absolved impure milk as the cause. “This of course was misinformation,” the bureau said.

Actually, it found, while bad milk was frequently to blame, the council erred by overlooking other contaminated foods and “excreta disposal.” It also placed undue emphasis on secondary sources of infection like nursemaids and cooks when their role was largely unsubstantiated, the bureau found.

In the end, John S. Billings, chief of the city’s Bureau of Infectious Diseases, meeting with investigators from the Bureau of Municipal Research on Jan. 28, 1914, agreed that except for some minor issues, the criticism was “just.” The city pledged to improve supervision of field work, check inspector reports and keep better track of milk purity including “use of telephones.”

It also issued guidelines that sound familiar today. “All persons nursing or handling the patient in any way should be careful to wash their hands very thoroughly with soap and water before leaving the sick-room. They should never, while in the sick-room, touch any article of food or put their hands to their mouths.”

By mid-1914, the city was recording record lows of typhoid among cities of over 500,000, with a 1913 rate, despite the outbreaks, of 7 per 100,000, better than many European capitals. The Times celebrated the progress on May 31, 1914: “LESS TYPHOID HERE THAN EVER BEFORE.”

But within four years, the euphoria gave way to a deadly new reality: influenza.

Ralph Blumenthal is a distinguished lecturer at Baruch College of the City University of New York, which houses the reports of the Bureau of Municipal Research as part of the Institute of Public Administration collection at the Newman Library. Sarah Rappo contributed research.