What does God look like? To American Christians, he looks like a white man.

In a study released in PLoS One this week, a team of psychologists surveyed 511 Christians—330 men and 180 women, with an average age of 47, from across the United States.

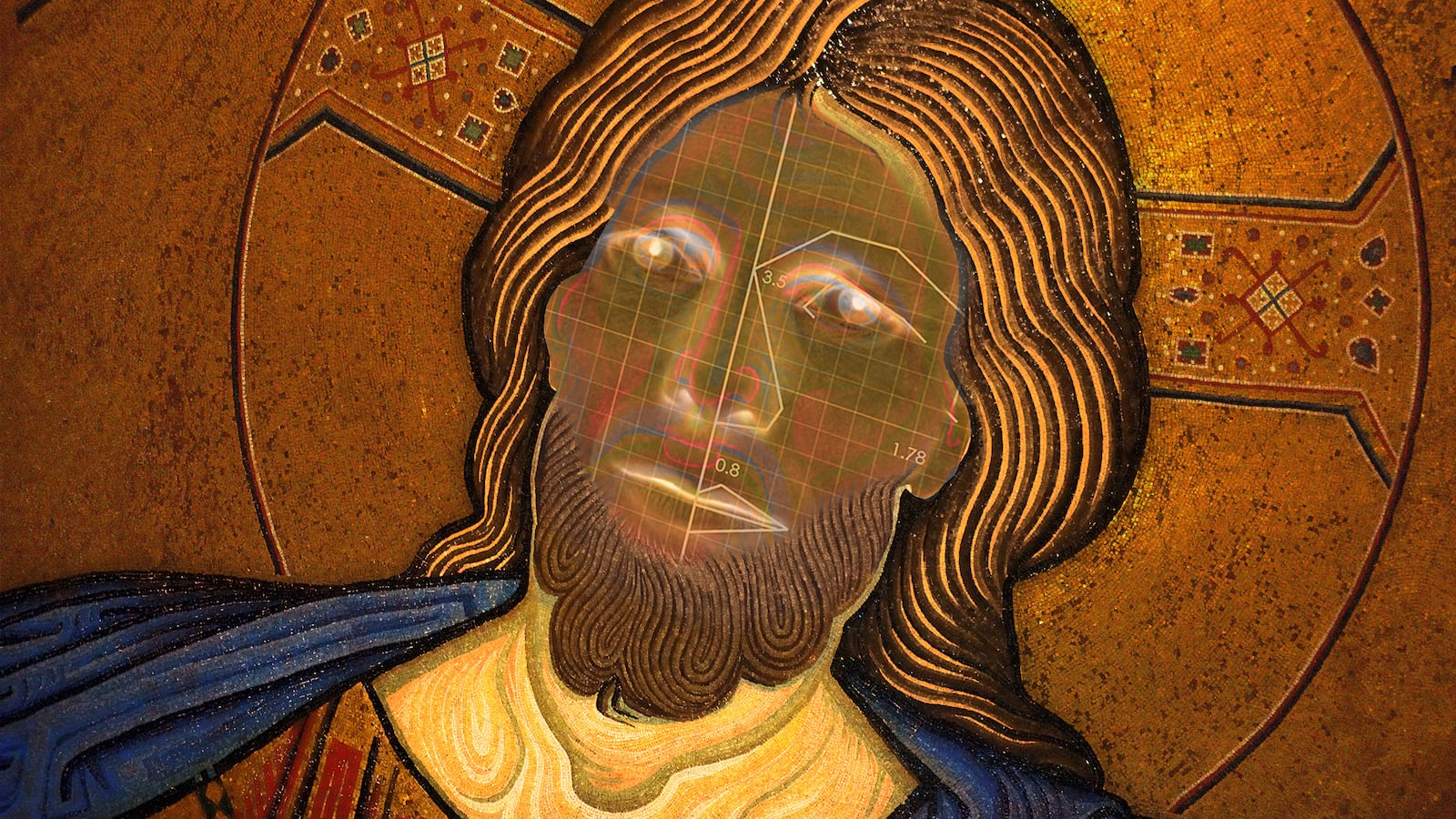

To figure out exactly how they thought God looked, the researchers ran a “reverse correlation.” The researchers began with 50 portraits of men and women that were specially selected because they represented the American demographic based on age, race, and gender. Each face was then adjusted so it varied in subtle ways—different eye color here, a change in smile there, a tad more hair perhaps, maybe a different nose. That group of adjusted faces was combined with the initial 50 portraits, then the second group was combined with each other. That combination of images was then shown to participants, who were then presented pairs of faces and asked which best represented how they imagined God.

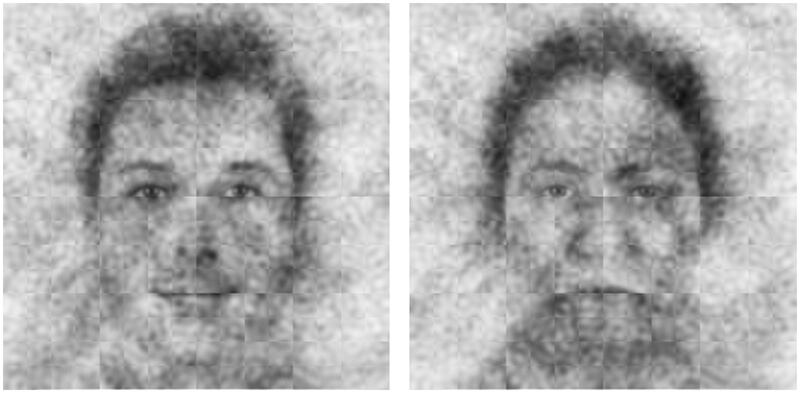

Turns out, God looked a lot like a nondescript white guy with a hint of a smirk.

That God was imagined to be a man is not necessarily surprising: For centuries, the Christian God has been referred to as He and Him, and the art world has long illustrated God as a masculine entity, most often an elderly, grandfatherly type with a beard and kind eyes.

But what is surprising is that the participants’ conception of God came down to who a person was. “It’s important to acknowledge that this bias [of a God who is masculine] wasn’t universal,” Joshua Conrad Jackson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told The Daily Beast via email. “There were political differences in how people envisioned God’s face and gender.” Indeed, when a liberal-leaning person thought about God, their God was more feminine, with softer features. Conservatives, however, saw a God with a harder jawline and a sterner visage, what was considered by researchers to be a more masculine face.

And it turns out, the God the participants imagined was heavily based on themselves.

“People appear to see God as looking like they do, at least based on age, level of attractiveness, and gender,” Jackson said. “This might be because when we think about entities we don’t fully understand, we use ourselves as a referent to fill in the gaps.”

From a psychological standpoint, it makes sense. The face of God is a mystery, and all the information Christianity presents about God as an entity is the pronoun He/Him. Because God is unfamiliar in this respect, our brains have a hard time conceptualizing a face.

That’s when insufficient “anchoring and adjusting” comes into play. That’s the psychological concept of using what we know to fill in the blanks, so to speak. God’s face might be an unknown, but what’s absolutely not is our own: the mug we’re stuck looking at in the mirror every day. Which means that reflection in the mirror gets transplanted in our heads with God, as we “anchor” our own beliefs and appearances with what we know (our face), and then “adjust” it away from that familiarity (OK, really, God couldn’t look exactly like that sinfully smug face in the mirror, so your brain adjusts it a little to make it just a tad more godly).

That the resulting God looked like a white man was also interesting given that the study was designed to have 25 percent African-American participation to test for racial bias. Black participants seemed to veer toward a whiter God, even though Jesus’ birth in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem would likely make him not white. It means the anchoring and adjusting process doesn’t quite work the same with black American Christians who envision God to be white. While Jackson couldn’t explain this phenomena beyond the fact that much of American art and culture has depicted Jesus to be white, therefore influencing non-white Christians to think of God as white, it presents an interesting question that Jackson hopes to understand in future studies: How does one anchor and adjust for an unknown entity without using yourself?

That said, despite the fact that black Americans in the study saw a whiter God, the study strongly shows that humans are narcissistic about how they view the world. Perceptions of God’s faces were in fact shaped indelibly by people’s own demographic standings: Black Americans saw a darker God, people considered more attractive similarly imagined a more attractive God, and younger people thought of God as just as young as themselves.

It’s nearly impossible to compare our conception of God to the historical one (“Our intuition is that people have viewed God as more loving and less authoritarian over the course of history,” Jackson said), but one thing that stands out universally is God’s hint of a smile, a sign of God’s reputation of being a loving, accepting being, signaled by fuller lips, bigger eyes, and the position of the eyebrows, Jackson said.

“We were surprised that people didn’t see God as more powerful or authoritarian, consistent with how God is portrayed in historic art,” Jackson added. “The average person perceives God as much more benevolent than we first expected.”

As for next steps, Jackson and his team hope to understand how culture plays a role, and whether those of different religions or those who self-identify as atheists imagine a godly being differently. Jackson also hopes to understand how political bias plays a subconscious role in shaping how we imagine entities and faces—something that’s already been done on the human level but hasn’t been studied in depth on a religious level.

“The conservatives’ God was perceived as more masculine, older, more powerful, and wealthier than the liberals’ God, reflecting conservatives’ motivation for a God who enforces order,” the study authors wrote. “Conversely, liberals’ God was more African-American (in appearance) and more loving than the conservatives’ God, reflecting their motivation for a God who encourages tolerance.”

At the end of the day, though, one thing stuck out in how this group viewed God. Overwhelmingly, men and women, white and black, young and old, saw God as a male entity. That’s probably cultural, and the authors note that as the tide shifts in being more open and flexible in describing and identifying with gender, so too might the way one thinks about God.