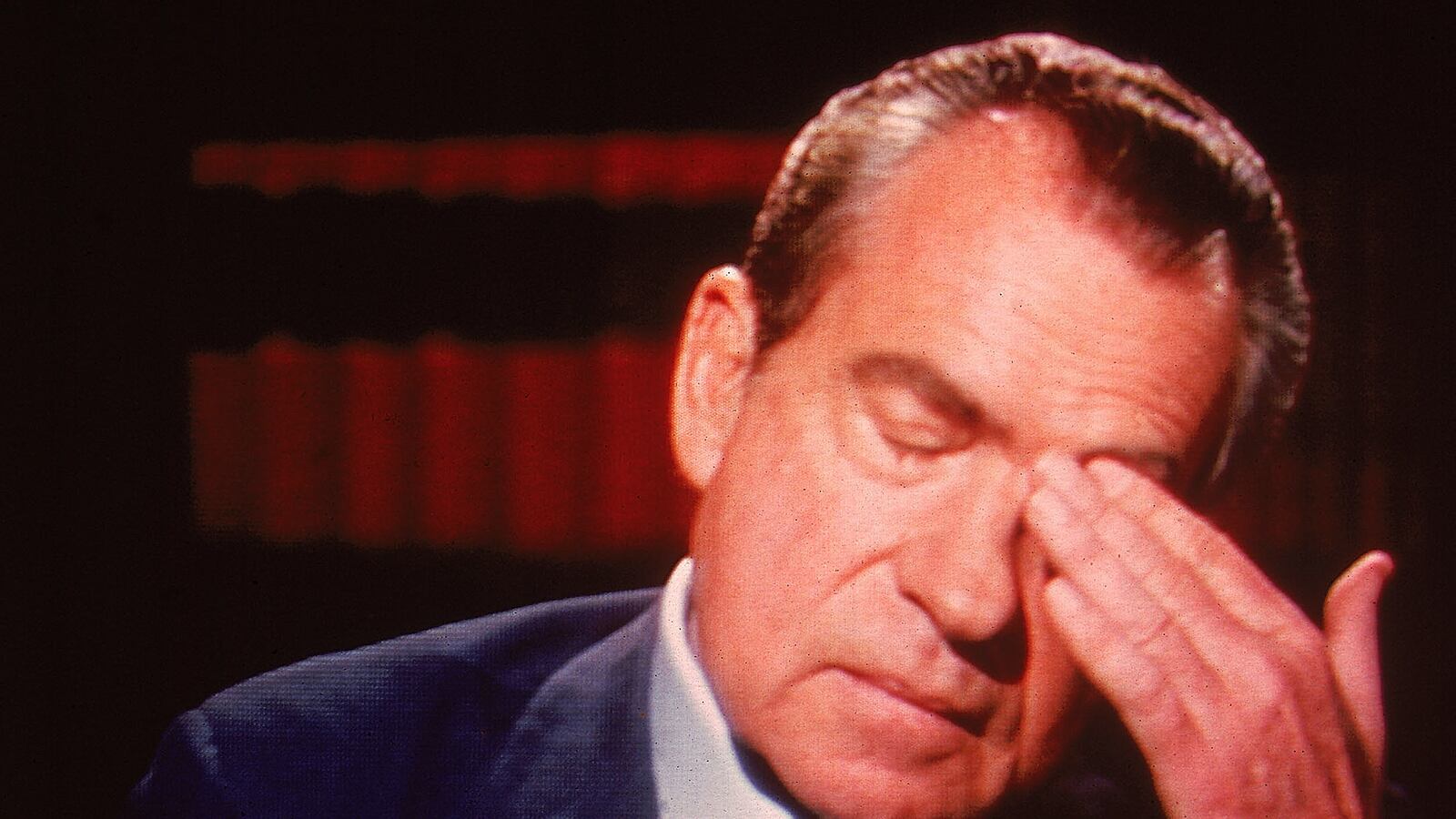

The shocking allegation is that a U.S. presidential candidate colluded with a foreign power in order to win the White House.

The parallel breathtaking allegation is that a U.S. president ordered the surveillance of a presidential candidate in order to prove he was in cahoots with a foreign power in order to win the White House.

The verdict of history looks to be guilty for all parties, including two presidents.

Importantly the year was not 2016, in the depths of the New Cold War with Russia, but rather it was 1968, in the depths of the Old Cold War with Russia.

I learn from new reporting by John Farrell, in his biography, Richard Nixon: The Life, that Richard Nixon guessed correctly from a telephone conference call with President Lyndon B. Johnson on Wednesday, Oct. 16, 1968, that Johnson was looking to announce a bombing halt in the Vietnam War in order to boost Democratic candidate Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s chances.

It was three weeks to the election. Nixon’s thin lead was fading. American Independent Party candidate George Wallace of Alabama was losing credibility with union Democrats in the Midwest, who were now rallying to the earnestly liberal Humphrey of Minnesota.

Nixon aide H.R. Haldeman’s notes from the day illustrate Nixon’s analysis: “RN thinks attempt by LBJ to get pause before election… danger is attempt to build up idea war is at an end.”

Nixon’s counter was to direct campaign manager John Mitchell to use a cut-out, Anna Chennault, to communicate to South Vietnam President Nguyen Van Thieu that he should not go along with Johnson’s gambit.

Chinese-born Anna Chennault, then 43, was the widow of World War II war hero General Claire Chennault of the Flying Tigers. She was also a Republican partisan known as the “Dragon Lady.” At Nixon’s direction, Chennault worked secretly with South Vietnam Ambassador to the U.S. Bui Diem to convince Thieu that he would get a better deal once Nixon was in the White House.

On Oct. 22, Haldeman’s notes of Nixon’s orders to Mitchell indicate the plan was in train: “Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN.”

Late at night, Nixon asked Haldeman about Johnson’s bombing halt plan, “Any other way to monkey wrench it?”

Johnson, a match of Nixon’s ruthless genius, heard talk of the conniving and ordered everyone wiretapped, from the untrusted ally Thieu in Saigon to the conspiring South Vietnam embassy in Washington to Anna Chennault’s home—and to vice presidential candidate Spiro Agnew’s campaign, perhaps even to Agnew himself.

Johnson read the wiretap reports: “Anna Chennault contacted Vietnam Ambassador Bui Diem.” Also, “She said the message was that, ‘Hold on. We are gonna win… Please tell your boss to hold on.’”

Over the next days, the NYT headlines recorded the Nixon vs. Johnson contest like an Allen Drury thriller.

On Nov. 1, we can read Johnson’s ploy to assist Humphrey to gain the peace vote: “Attacks on North Vietnam Halt Today: Johnson Says Wider Talks Begin Nov. 6.”

On Nov. 2, we can see Nixon’s ploy to wreck Humphrey’s late momentum: “Thieu Says Saigon Cannot Join Paris Peace Talks Under Present Plan; U.S. To Step Up Bombing In Laos.”

Johnson was volcanic and called Republican Minority Leader Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois on Nov. 2. “This is treason.”

Nixon learned immediately of the Johnson charge and told Congressional Republicans, through Haldeman, how to treat Johnson and the Democrats: “Kick them hard…”

Cooly, Nixon called Johnson on Sunday, Nov. 3—48 hours to the vote—and acted chagrined at the allegation. “My God, I would never do anything to encourage… Saigon to come to the table.”

Johnson suspected the worst and was urged to expose Nixon’s arguably Logan Act felonious game.

Johnson and Humphrey chose silence. Why? Perhaps, Farrell reasons, because they did not have direct proof of Nixon’s involvement—such as can be found in Haldeman’s notes.

Perhaps, too, exposing Nixon would mean revealing that Johnson had used the FBI to wiretap a presidential campaign.

Nixon also remained silent and worked to his death in 1993 to keep Haldeman’s notes out of the news. The U.S. government, which had taken possession of Nixon’s files in 1974, did not make the necessary documents available until 2007.

John Farrell reports in a footnote that he “found Haldeman’s notes on the Chennault affair while conducting research for this book.”

Even without those notes as proof, it has not escaped ironic observers the last 50 years that Nixon learned from the scrap with Johnson that there was a thrilling pay-off to fighting your opponents without limits of law or common sense.

Did the same kind of high-stakes intrigue show itself in the Watergate affair of 1972-74?

Farrell quotes from Johnson’s aide Walt Rostow’s 1973 memo about the Chennault affair, “They got away with it. As the same men faced the election of 1972 there was nothing in their previous experience with an operation of doubtful propriety (or, even legality) to warn them off…”

Thanks to Farrell’s delightful labor, what I have learned from the Chennault affair is that it can take decades to unpack the chicanery during presidential elections.

How I celebrate you who will read the facts of the allegations of collusion and surveillance of 2016 in the year 2066.