“That shit is kinda crazy, cuz at school I always used to listen to Michael Jackson, Marvin Gaye, Al Green, whatever. Now I look at it like: he’s the biggest—he’s bigger than me—but ain’t nobody else bigger than me but Michael Jackson.”

There had never been a pop star like Snoop Doggy Dogg.

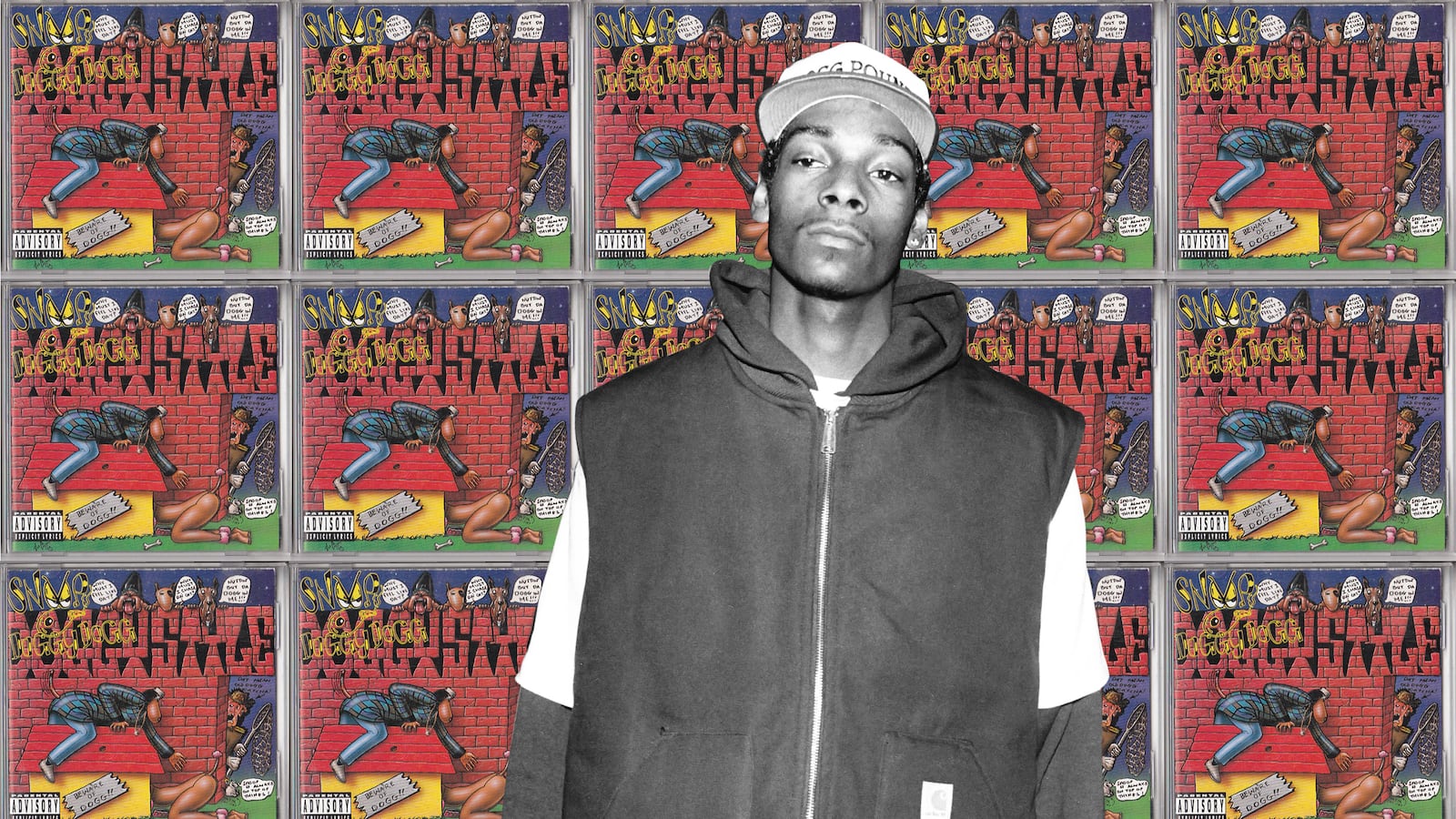

And make no mistake, in the fall of 1993, when he was just a laid-back 23-year-old with a distinctive drawl who had only been famous for less than two years, the man born Calvin Broadus was already exactly that—a pop star (albeit not of the Vanilla Ice or MC Hammer variety). Snoop dropped his debut album in late November of that year, which sold 806,858 copies in its first week—a record for an artist debut—and he’d become the most talked-about artist in hip-hop. He was as known to mallrats across Middle America as he was to hustlers on corners in the roughest hoods. And we’d never seen anything like it. Because this was some gangsta shit.

Snoop’s debut was already the most anticipated album of the year. Famously, he’d made his first appearance on Dr. Dre’s single “Deep Cover” in early 1992. That song was Dre’s first major moment after departing N.W.A. and Ruthless Records acrimoniously in 1991, ditching his former friend Eazy-E to launch Death Row Records with former bodyguard Suge Knight via a lucrative deal with Interscope Records’ Jimmy Iovine. Not only did “Deep Cover” announce the hit-making rapper/producer as a formidable solo artist, it made the lanky Long Beach kid with the funny name the most buzzed-about new voice in rap music. As much as 1991’s Main Source’s “Live At the BBQ” did to make teenage Nas the “chosen one” amongst East Coast hip-hop aficionados, “Deep Cover” and Dr. Dre’s opus The Chronic made Snoop the most exciting newcomer in the rap game’s mainstream. He’d been on the cover of Rolling Stone that September and was featured in Newsweek. People who wouldn’t know Nas’ name for another three years knew exactly who this Snoop Doggy Dogg was—and not everyone was a fan.

The popularity of The Chronic, as well as high-profile controversies surrounding West Coast rap stars like Ice-T and Tupac Shakur, meant that gangsta rap had become the scourge of 1993. In N.W.A., Dr. Dre had been there for the dawn of hip-hop-vs-the-cops but he’d also been one of the chief purveyors of gangsta-rap misogyny. N.W.A.’s Niggaz4Life wallowed in over-the-top murder and mayhem, and with song titles like “One Less Bitch” and the interlude “To Kill a Hooker,” women were the targets of the music’s most heinous moments. The popular video for “Nuthin’ But A G Thing,” Dr. Dre’s Snoop-spotlighting monster hit from late 1992, ended with Dre and his protégé spraying malt liquor over an unsociable woman, ostensibly as punishment for her rebuffing strange men’s advances at a house party. And The Chronic itself ends with the notorious “Bitches Ain’t Shit,” with Snoop providing the gleefully woman-bashing chorus.

Such subject matter would put Snoop square in the sights of feminists and moral watchdogs across America, the poster boy for the rising menace of gangsta rap. His notoriety would only increase after the tragedy of August 25, 1993, when Philip Woldemariam was shot by Snoop’s bodyguard, McKinley Lee. Snoop surrendered to police after appearing at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards in L.A. before posting the $1 million bail. Snoop was facing a murder charge—and he was the most famous rapper in music. Lee and Snoop pleaded self-defense, as the world sat waiting to see how it would all play out. It was bizarre and enthralling for a mainstream fanbase still new to rap music and with “gangsta” culture all the rage at the box office and on the charts. (Snoop was acquitted in 1996.)

Despite the misogyny and murder charge, Doggystyle is arguably a more fun record than The Chronic. It would be three more years before Snoop and 2Pac would croon “Ain’t nuthin’ but a gangsta party” on Pac’s hit “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” but that would aptly describe Snoop’s 1993 debut. The production is as moody and melodic as The Chronic had been before it, but there’s a strange zest for life sprinkled amidst songs like the apocalyptic “Murder Was the Case.” That dark deal-with-the-devil tale is actually more of an anomaly; the majority of Doggystyle is dedicated to blunts, boasting and raunchy hijinks. It’s a party.

“The Chronic is sonically incredible, but it’s hard to drive around singing songs about, ‘Eazy-E can eat a big fat dick,’” Chris Rock once wrote. “But I got a feeling I’ll be singing ‘Gin and Juice’ when I’m ninety.”

Snoop’s slickness was, in many ways, what made him scarier than an Ice-T, 2Pac or Ice Cube had been up to that point. With that melodious flow and penchant for singsongy hooks riding over infectious G-funk production, Snoop made music that could go places the shouted rage of “Cop Killer” or early ‘90s Ice Cube and “Holler If Ya Hear Me” 2Pac couldn’t. Rappers had been under fire for anti-cop lyrics throughout 1992, but somehow Dr. Dre’s “Deep Cover” missed all of the controversy. As Toure wrote in The New York Times back in 1993:

Both songs gained popularity in the summer of 1992, but “Deep Cover” did not provoke the controversy “Cop Killer” did because of Snoop’s subtlety: to understand “Deep Cover’s” refrain—“‘cuz it’s one eight seven on a undercover cop”—one has to know that in Los Angeles police terminology the number 1-8-7 means homicide.

“It’s the way you put it down,” Snoop explained back then. “I put it down with a twist. Everybody in the whole world knew ‘Cop Killer’ meant kill a cop. And every policeman knows the municipal code is 187, but everybody in the whole world didn’t know that.”

Snoop put it down in a way that got him played in R&B and pop circles. The assumption at the time was that Dr. Dre was the musical Svengali behind everything coming out of Death Row, but with Snoop’s debut, Dogg Pound rapper/producer Daz (the erstwhile “Dat Nigga”) handled the bulk of the production.

“[It] was was pretty much luck,” Suge Knight said in 2013 of the album’s sound. “Everybody thought [Dr. Dre] would be doing the records, but Daz pretty much did the whole album. And at the end of the day, once Daz finished it, everybody wanted Andre to get the credit. Next thing I know Daz is having a meeting with Andre and them and came back and said, ‘It’s okay, give me a few bucks and I’ll sign anything over that says produced by Andre instead of me.’”

In that aforementioned Guardian interview from 1994, Snoop doesn’t hesitate to mention himself alongside the biggest names in music history, from MJ to Elvis (“I deal with shit nobody else has done before. Not even Elvis.”) There was also an air of mystery around the rapper; a 1993 SPIN article cites his birth name as Cordazar Varnado, after his father, not the more well-known Calvin Broadus; there was uncertainty about his birth date and just how much time he’d done as a teen. He was called upon to answer for his lyrics, but not as a politicized firebrand a la Cube or Pac—he seemed to represent himself unpretentiously. His early interviews reveal how confident he was, but also there’s an “aw shucks” in his commentary (“There’s some good police, I can’t even lie”) alongside typical double standards regarding sex, respectability and power (“I dislike women who conduct themselves as bitches and hoes or groupies…”).

In the tradition of so much hip-hop, Snoop became a superstar without ever seeming like he cared to be one. And he recalibrated hip-hop’s mainstream. Since the late 1980s, rap’s biggest crossover stars had typically possessed a non-threatening universality: Kid ‘N Play’s likeable youthfulness, Heavy D’s overweight lover, Salt-N-Pepa’s round-the-way spunk—it was all easily marketable to R&B and pop audiences who didn’t want to hear four-letter words or gritty street tales. But Snoop wasn’t smiling, singing or safe—and after 1993, nobody else had to be.