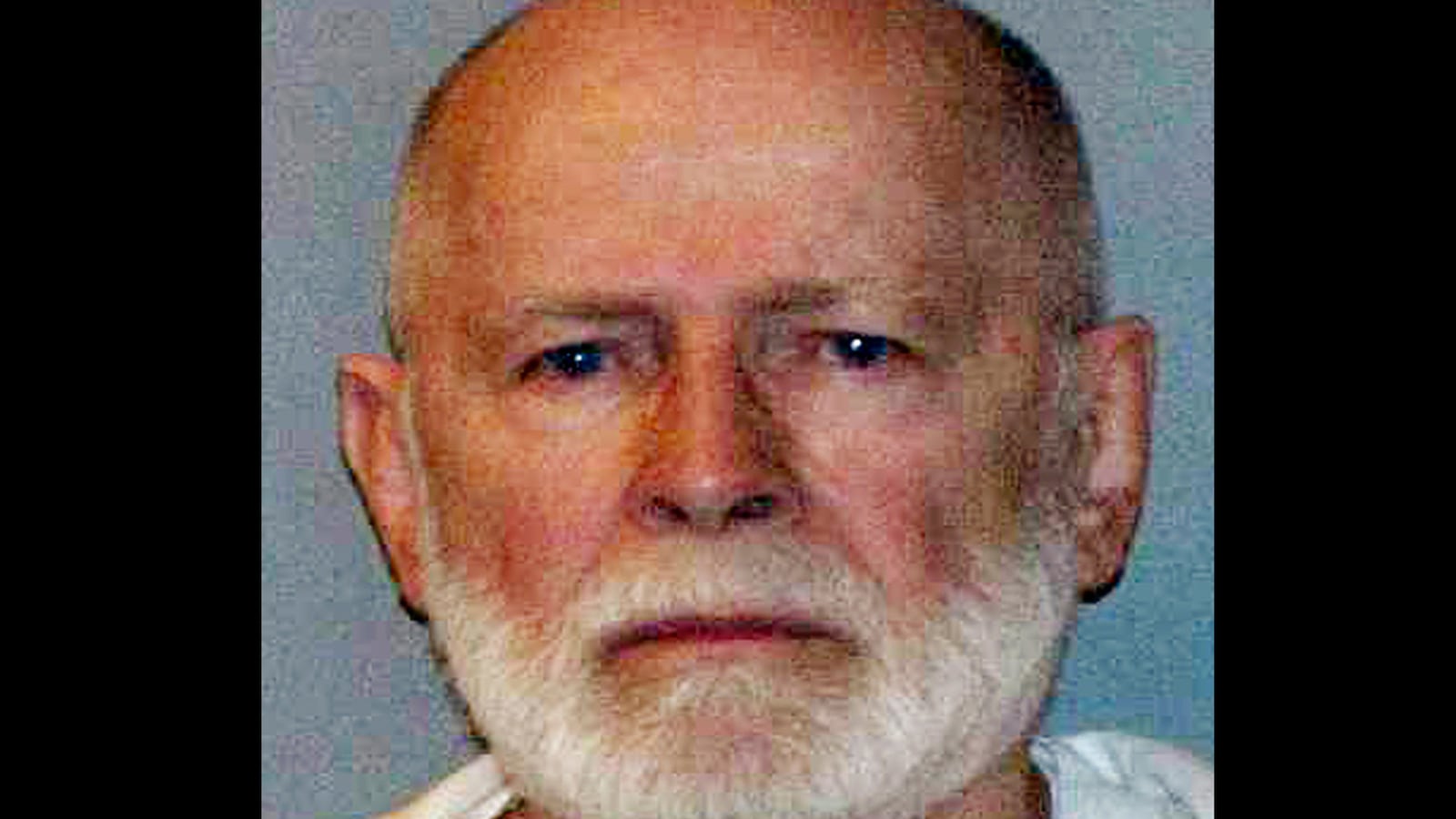

As the most infamous gangster in the history of Boston stood to address the court, you could have heard the sound of a faucet dripping in Mongolia. Other than a few choice expletives dropped here and there throughout the course of his long federal racketeering trial, mobster James “Whitey” Bulger had yet to be heard from. Now, with the defense about to rest its case and the jury out of the courtroom, Judge Denise Casper asked the defendant if his decision not to take the stand and testify in his defense was being made “voluntarily.”

“I make the choice involuntarily,” said Bulger. “Because I feel I’ve been choked off from having an opportunity to give an adequate defense and explain about my conversation and agreement with Jeremiah O’Sullivan. For my protection of his life, in return, he promised to give me immunity.”

At the sound of the word “immunity,” which had been all but banned from the proceedings, Judge Casper interrupted. “I have considered that legal argument and made a ruling. I understand, sir, if you disagree with it, okay?”

In a dark blue, long-sleeved t-shirt, looking pale and dispirited, Bulger said, “I know. But I do disagree, and that’s the way it is. As far as I’m concerned, I didn’t get a fair trial, and this is a sham. Do what youse want with me. That’s it. That’s my final word.”

From the spectator gallery, Patricia Donohue—the widow of a man Bulger is accused of having murdered—shouted out, “You’re a coward.”

The judge asked for order among the spectators.

The jury was brought back into the courtroom.

J.W. Carney, Bulger’s attorney, announced to the judge, “The defense calls no further witnesses, and we rest at this time.”

It was an anti-climactic interlude in a trial that has had many moments of drama. Before the trial began, Carney repeatedly promised that Bulger would take the stand. To the media and at pre-trial hearings, the lawyer oversold his client’s defense, making it sound as if Whitey were ready to “tell all” about his role as a Top Echelon informant for the FBI. Throughout the trial, Bulger had appeared feisty, exchanging heated words with one former associate and, during the testimony of a corrupt FBI supervisor, barking out, “you’re a fucking liar.”

But when it came time for Bulger to take the stand and speak for himself, like a fighter who was overwhelmed and out of tricks, he refused to come out of his corner and answer the bell.

There will be the inevitable taunts and innuendo that Bulger, by choosing to exercise his constitutional right not to testify, has displayed a lack of manliness. In truth, his claim that the trial has been a “sham” has elements of validity. Aside from the entertainment value his taking the stand might have provided to the media and spectators for whom Whitey Bulger has become the city of Boston’s Great White Whale, his testimony would have been an exercise in futility.

In a trial that has lasted 35 days and included testimony from 72 witnesses, the prosecution has overseen a cavalcade of evidence that has been nearly flawless from their point of view. Facilitated by Judge Casper, who has ruled in favor of the prosecution in various evidentiary motions nearly ninety percent of the time, the government has successfully contained the evidence to focus on a specific sequence of criminal acts perpetrated by Bulger. There has been little in the way of evidence about O’Sullivan, head of a federal Organized Crime Strike Force in the U.S. District of Massachusetts, who served as one of Whitey’s key protectors in the criminal justice system for years. Any time there is testimony that seems to hint at the historical framework of systemic corruption that enabled Bulger, the prosecution objects, and the judge sustains their objection.

There has never been much doubt that Bulger would be found guilty of many, if not all, of the criminal counts in the indictment. He was a psychotic mob boss who terrorized, extorted and killed people in the city’s criminal underworld for more than twenty years. But many who have been following the Bulger saga had hoped the trial would be a full and final accounting of the corrupt culture in law enforcement and politics that made Bulger possible. Initially, Whitey also seemed to want to use the trial as an opportunity to get the full story out on the table, putting many spectators, journalists and even family members of victims of his crimes in the unusual position of rooting for the defense to make its case.

The frustration expressed by Bulger is shared by many who had been hoping for more. Whitey has declared that he will not be a party to a “sham.” Some will declare him a coward, but, in fact, this trial was not conceived of or designed to facilitate Bulger coming forward to tell all that he knows. The trial has been designed to bury Bulger and all that he knows.

Closing arguments for both the prosecution and the defense are scheduled to take place on Monday.