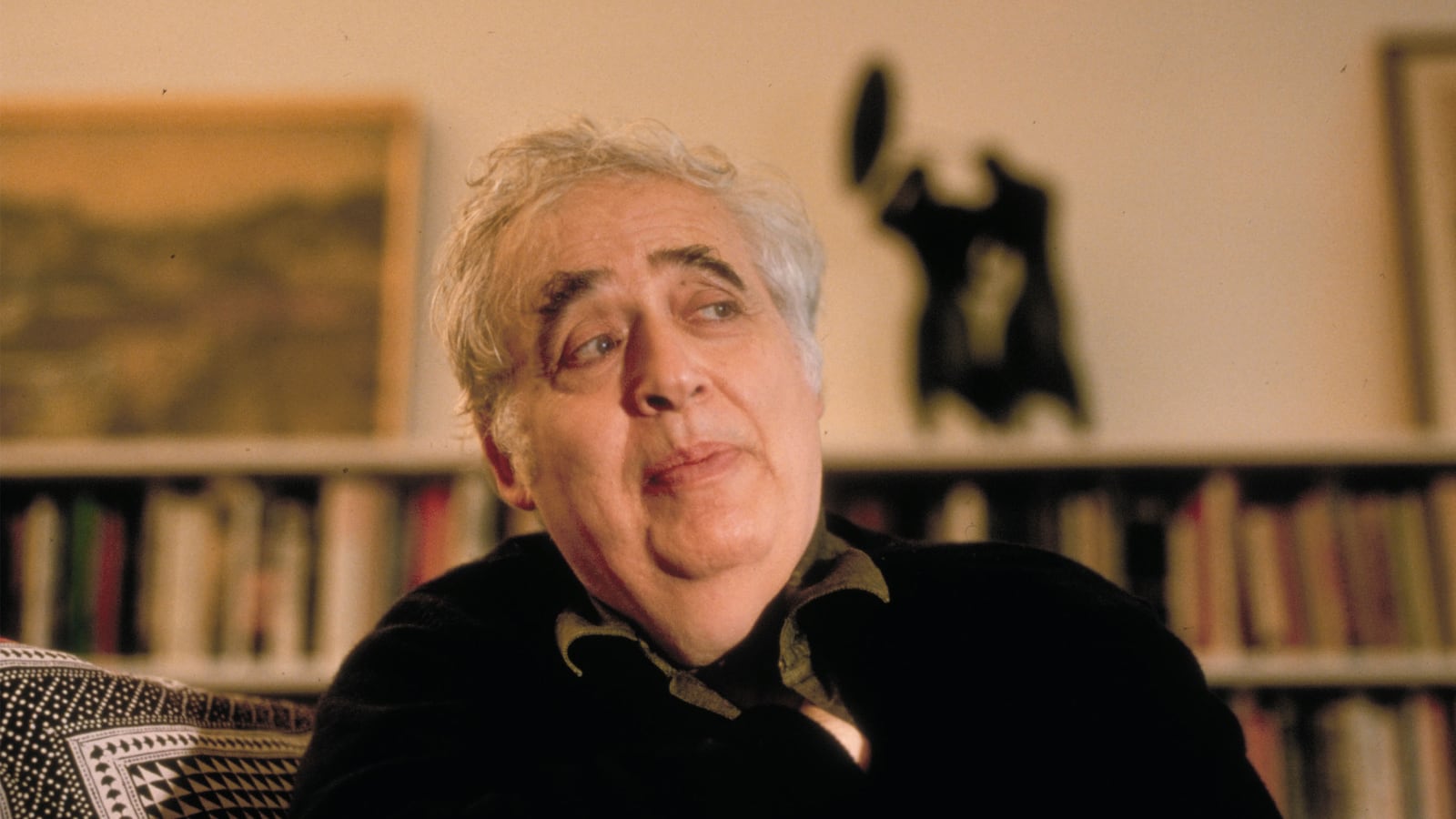

Harold Bloom has read more books than you, and has internalized them as well as anyone can. You may not agree with all of his views, but he would not want you to anyway. For Bloom, reading, like writing, is a solitary activity, though one never done in isolation from other writers.

He was born to a Yiddish-speaking family in The Bronx in 1930, and has been teaching at Yale since 1955, where, for decades, he has been the Sterling Professor in the Humanities. He is the author of more than 40 books and the editor of hundreds, on subjects ranging from The Anxiety of Influence (a phrase that is part of our lexicon) to The American Religion, from The Western Canon to Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. In his new book, The Daemon Knows: Literary Greatness and the American Sublime, he turns to 12 American writers for wisdom, in search of the national soul and the divinity at the core of the national self.

Bloom has reached out beyond the academy to solitary readers everywhere. In July, he will turn 85, and though he is becoming skeptical that these readers will continue to exist, he soldiers on anyway. He spoke to The Daily Beast from his home in New Haven, where our discussion of the American Sublime took us from Wallace Stevens to a memory of giving the great bebop pianist Bud Powell a collection of Hart Crane’s poetry.

You have an idiosyncratic way of defining the word “daemon.”

I do it very thoroughly in the book, following Eric Robertson Dodds, who I knew here at Yale and in England. The daemon is man’s potential divinity.

Are you using it in the sense that Socrates used it in Plato’s Symposium?

No. Of course we do think of the daemon of Socrates, but it’s much older than that. It has Orphic origins, it has shamanistic origins. You could trace it to the Roman word “genius,” I suppose. It’s the notion that there’s a god within us, and the god speaks. The daemon is the sublime inspiration.

And so you were inspired to write this book.

In particular, I thought of the dozen American writers I gathered together in this book. I worked very hard on the book for five years, punctuated by hospital stays and terrible falls. Now that it’s being published, I feel a little sad about it, because I’m losing an old friend, but also because I fear that it will not find very many readers. We are now so far gone in what used to be called our literary culture that the readers are just not there for it anymore. I hope I’m wrong.

You must find some hope in your undergraduates at Yale.

But you know I don’t write for my own students and I certainly don’t write for other academics. I write for solitary readers everywhere. I don’t know how many of them will realize that this book is what they need and want. I’m too realistic to hope for too much.

Well, you’ve read everything. That has to count for something.

Of course I’ve read everything, but that isn’t the strength of the book, I hope.

What do you see as the strength of the book?

For three years, I saw this book as a kind of personal bridge, leaping from Walt Whitman to Hart Crane and then back again, though I think all 12 figures in it are great writers, including the one I personally dislike, Mr. Thomas Stearns Eliot. Walt Whitman is probably the greatest American writer, and the American writers I love best are Walt Whitman and Hart Crane. I was surprised when I read the proofs and I thought the treatment of Moby-Dick was the best I had ever managed. The treatment of Hawthorne surprised me. I thought the Henry James was well done. I thought the Dickinson was astonishing because it shows her links to Shakespeare. And then I had a very strong feeling that Huckleberry Finn is well covered in the book, and that I had done justice to Robert Frost’s best poems. And I did better by three of Faulkner’s five great books.

And then the chapter that interested me most was the elaborate, subtle war staged by one of my favorite poets, Wallace Stevens, against Eliot. And yet at the same time, I tried to be fair and I granted certain things in Eliot, like the great sequence in “Little Gidding,” which really has astonishing power.

It’s clear that you, at least in your section on “Little Gidding,” are trying to make peace with T.S. Eliot.

Well, it’s a very dubious peace, a Virginian peace, you might say. The whole thing ends, of course, with my love letter to Hart Crane. The letter to Hart poured out of my heart. It’s his own pun. Since I was 10 years old, he really converted me to my lifelong obsession with poetry.

Hart Crane is not an obvious place to start, especially for a 10 year old.

I started with Yiddish poetry. I read Crane simultaneously with Shakespeare, with Shelley, with William Blake. There was something about Crane, from the beginning, that spoke to me in a special way.

And what was it about Crane when you were so young? You’re a New Yorker, so you knew the Brooklyn Bridge he was writing about.

Kenneth Burke and I used to clamber it together. Kenneth, wonderful old man, Kenneth took me on as my mentor after he reviewed The Anxiety of Influence and A Map of Misreading. We spent a lot of time together. And Kenneth had been very close to Hart Crane. He rented Crane the room in which he lived for years. He lent Crane money. He had a strong effect on my view of Crane. He said that he always felt that, for Crane, bridge was cognate for bride. And that’s the way I see it now. If I live to do it, I am trying to write a final book called One Song, One Bridge of Fire, which is taken from near the close of “Atlantis.” I think of it in terms of “A Bride of Fire.” That’s what Crane was seeking. He was finding his bridge, whom he otherwise couldn’t find, in the bridge itself.

You gave a copy of the Collected Poems of Hart Crane to Bud Powell.

Yes, not the copy that was the first book I ever owned, a gift from my sister for my 12th birthday, but the old black-and-gold Liveright edition. I gave it to him because I had been transfixed by his three versions of “Un Poco Loco,” with Max Roach, who eventually became a friend. They are on that great Blue Note recording The Amazing Bud Powell. Who was the bass player?

Curly Russell.

Yes, Curly Russell. I was so overcome by the final version of “Un Poco Loco” where everything seems to break loose at once, and Max is really going to town with the full ensemble of the percussion. So I was sitting having a drink with Bud, and I said, “You know, I can’t help but hear, in my own head of course, overtones of Hart Crane’s greatest poem, ‘The Broken Tower.’” Bud was a very strange guy to watch. He basically played with one hand. He played with the right hand and used the left hand only for doubling. I said to Bud, “This is anxiety of influence.”

You used that term then?He said nobody could match Art Tatum. And I said, “I think it’s your homage to Tatum that you don’t use the left hand, because Tatum’s left hand was extraordinary,” like the great Arthur Rubinstein himself. But I also said to him, that it was like that great moment in “The Broken Tower”: “The bells, I say, the bells break down their tower; / And swing I know not where.” So I gave him the book and he read it. He didn’t read every poem in it, but he read most of The Bridge, and he read “The Broken Tower” several times.

Maybe “Black Tambourine”?

Yeah, “Black Tambourine.” We talked about “Black Tambourine.” We talked about what I think of as the greatest single poem by Crane except for certain parts of The Bridge, that amazing poem, “Possessions,” which begins “Witness now this trust!”

I am reminded of something you wrote in the ’80s in an introduction to a collection of essays on Thomas Pynchon. You wrote of the American Sublime, and you included the authors in The Daemon Knows, but you also included Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, W.C. Fields’ “The Fatal Glass of Beer.”

I remember recalling Charlie Parker’s “Parker’s Mood”…

…and also his recording of “I’ll Remember You”…

Yes. Both incredible numbers.

Did you ever consider writing about Bud Powell or Charlie Parker?

No, I’m not a jazz critic. I appreciate jazz of a certain kind, that tradition that really emanates from an aspect of Louis Armstrong and then goes on to Roy Eldridge and is picked up by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Mingus, and Max and so on. It really culminates in early Coltrane, before he gets religion. I could do without A Love Supreme. Early Coltrane is a marvelous agon with Charlie Parker. I have read you on Hart Crane and jazz in your book Fascinating Rhythm. I wanted to discuss Crane in enormous detail and I couldn’t do it without rereading what you wrote about Crane’s jazz references in “The Marriage of Faustus and Helen.” I think the most important thing I do with Crane in the book is what I’ve been doing with my students. It’s to say, “Look, The Bridge becomes a completely different poem if you take it in the order in which the daemon composed it, so that it starts with ‘Atlantis’ and ends with ‘Southern Cross’ and ‘Virginia.’ And you just omit those poems written in late 1927,’ when he was an alcoholic in despair.’ Kill most of ‘Cape Cape Hatteras’ and that awful ‘Indiana.’” I tell them, “Look, throw that out and read the poem in exactly the order in which it was composed. It becomes a very different and even greater poem.”

You have this incredible description of going to Yale for the first time to see Wallace Stevens in 1949.

I was a Cornell undergraduate, and I’d heard that Wallace Stevens, whose poetry I worshipped, back to the days when I was 13 or 14 years old, was reading a poem that was then called “The Ordinary Evening in New Haven.” It was a shorter version of it. It was at something called the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. So I took the train up from New York City and crashed the occasion. I felt very out of place. And a future colleague, Norman Holmes Pearson, noticed me and pulled me to the poet, because nobody was talking to him. He dragged me over and introduced me. Stevens was very charming and very gentle, very friendly. Interestingly enough, we talked about Shelley. We talked about “The Witch of Atlas,” which is not exactly a poem most people read.

What else did you talk about?

Whitman, but he didn’t want to talk about Whitman. But he liked talking about Shelley. He was very guarded about Whitman.

Interesting.

Well, you can see why. Isn’t it strange? People always think of Stevens as a buttoned-down kind of fellow, the Hartford Major Life Insurance executive, a highly respectable fellow. And it isn’t Hart Crane, but Wallace Stevens, who suddenly bursts forth into the most ecstatic, loving and accurate lines about Walt Whitman ever written. Who would believe that this was Wallace Stevens?:

In the far South the sun of autumn is passingLike Walt Whitman walking along a ruddy shore.He is singing and chanting the things that are part of him,The worlds that were and will be, death and day.Nothing is final, he chants. No man shall see the end.His beard is of fire and his staff is a leaping flame.

Beautiful. This reminds me: Do you think that in “The Idea of Order at Key West,” when Stevens is quarreling with Ramon Fernandez, that he was really referring to the other RF—Robert Frost?

I met Robert Frost at the Breadloaf School, and I found him to be a very canny, very powerful, rather unpleasant person. That’s what Alfred Kazin said.

Great poet, but kind of a nasty man. Very bitter, very sour. Very, very clever. “Directive” is as good as any poem could be.

Were there certain writers that you were thinking of including that didn’t make the cut?

I wanted just 12. I have an alternative 12. I suppose a personal regret is Nathanael West. Miss Loneleyhearts is an astonishingly daemonic work.

What about Elizabeth Bishop?

I thought long and seriously about Elizabeth, but I didn’t want 13 but 12. I suppose as a Hebrew of the Hebrews, I always think in terms of 12 tribes.

What about Ralph Ellison?

Ralph was a good personal friend. He was on my alternative list. Invisible Man is a great book. Kenneth Burke taught me that it was a book of the eminence of The Magic Mountain. I think so, too. There were so many I had to leave out. I just wanted 12. As it is, the book is about 500 pages, so you have to consider what a publisher will tolerate and what an audience is willing to take on to itself. That is, I thought I was straining the limits that one can have these days.

What American novelists in our time do you think will survive?

I would not include Saul Bellow, who I didn’t like as a person or as a writer. It would be Philip Roth and Sabbath’s Theatre and American Pastoral, Don Delillo for Underworld, Cormac McCarthy for Blood Meridian, Tommy Pynchon for three books anyway, the early and magnificent The Crying of Lot 49, and then certain moments scattered through Gravity’s Rainbow, and then Mason & Dixon, which is quite a formidable book.

So you dislike all of Saul Bellow?

All. Aside from the fact that we didn’t get along, I don’t think he’s the writer they say he is. The best book, the only one I can reread, is Humboldt’s Gift, and that’s partly because I knew Delmore Schwartz pretty well. It’s Delmore’s book. He had a great gift for caricature.

What is the book’s largest accomplishment?

Ultimately, I think the greatest achievement of The Daemon Knows is the treatment of Walt Whitman, because it’s the only treatment of Whitman which really does deal with the six major poems. It really does show how magnificently they work. What did you like best in the book?

I loved your very personal ending with Crane. I found it so moving. I liked the way you talked about your initial discovery of his poems as a boy, and then how your reading of him developed over many decades.

Yes, I have changed almost completely. I hadn’t realized the extent to which, in the end, it isn’t Blake, it isn’t T.S. Eliot, it isn’t even Walt Whitman, it isn’t even Shakespeare or Marlowe, the deepest influence on Crane. It’s Shelley, founded upon “Adonais.”

And your first book was on Shelley.

Yeah, way back there. His song from “Prometheus Unbound” is a clear source for one of Crane’s “Voyages,” which gives a basic pattern for all of Crane’s poetry. Crane is, after Shelley himself, the most Shelleyan poet in the language. And like Shelley, he’s essentially Pindaric.

You end the book quoting Shelley on the sublime, “to persuade us to abandon easier for more difficult pleasures.”

I think that’s what Crane is doing. He’s a difficult poet, but he really teaches you to throw away cheap effects by bad poets or half-good poets and go into the powerful difficulties of his work, sources of enormous insight. Probably only Faulkner matches it in American literature. He has a real openness to the daemonic influx.