Is it “the world’s most dangerous book?” The BBC thinks it might be. Esquire has no doubt, declaring it “the most evil book in history.” The Independent wonders, coyly, if it’s “too dangerous for the general public”—a headline guaranteed to bring the general public running.

It’s a quote, it turns out, from a historian at the Bavarian State Library, explaining why timeworn copies of what The Independent calls the “toxic text” are “kept in a secure ‘poison cabinet,’ a literary danger zone in the dark recesses of the vast” library. The book is Mein Kampf, of course. Hitler’s megalomaniacal memoir-cum-genocidal manifesto is in the news again because, on the last day of 2015, it entered the public domain in Germany and, for that matter, the rest of continental Europe. (Contrary to urban legend, owning Hitler’s book was never illegal in Germany; copies could be found in libraries, antiquarian bookshops, and on the black market, in pirated editions produced by neo-Nazi publishers.)

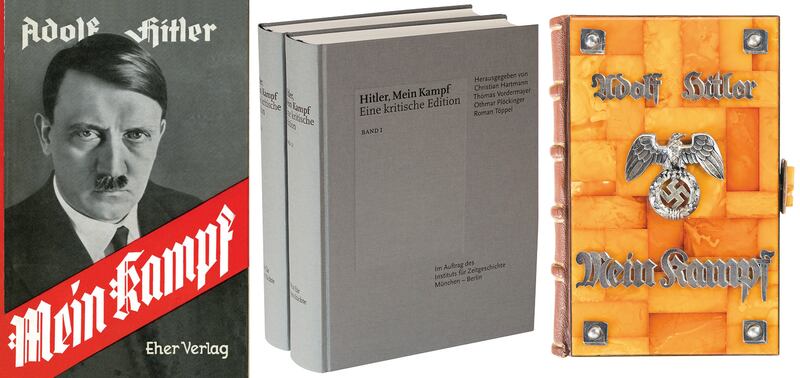

When the copyright lapsed, the Munich-based Institute for Contemporary History, a government-funded body that researches the Nazi era, was quick off the mark with its two-volume “critical edition” in German. And they do mean critical: Hitler, Mein Kampf—Eine Kritische Edition includes nearly 3,500 annotations, swelling Hitler’s already bloated tome from 800 to nearly 2,000 pages. If the constant drizzle of scholarly commentary doesn’t rain on the neo-Nazi parade, the sheer length of the thing—a literary death march, if ever there was one—is calculated to thin the ranks of Hitlerphiles through terminal boredom. (One former Nazi claimed, in all seriousness, that Mein Kampf began as a diversionary tactic, a way of tricking Hitler into giving his jaws—and his long-suffering comrades’ ears—a rest. According to the historian Ian Kershaw, a Party member doing time with Hitler in Landsberg prison for the failed 1923 putsch, had the “’Machiavellian idea’ of suggesting to Hitler that he write his ‘memoirs’ in order to relieve ... the other inmates of having to listen to endless monologues.”)

Hitler’s writing, like his table talk, is pure chloroform. “He can be Führer as much as he likes but he always repeats himself and bores his guests,” groused Joseph Goebbels’s wife, Magda, after one too many lunches listening to the Great Man gassing off. Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect, pegged him as “that classic German type known as the Besserwisser, the know-it-all. His mind was cluttered with minor information and misinformation about everything.”

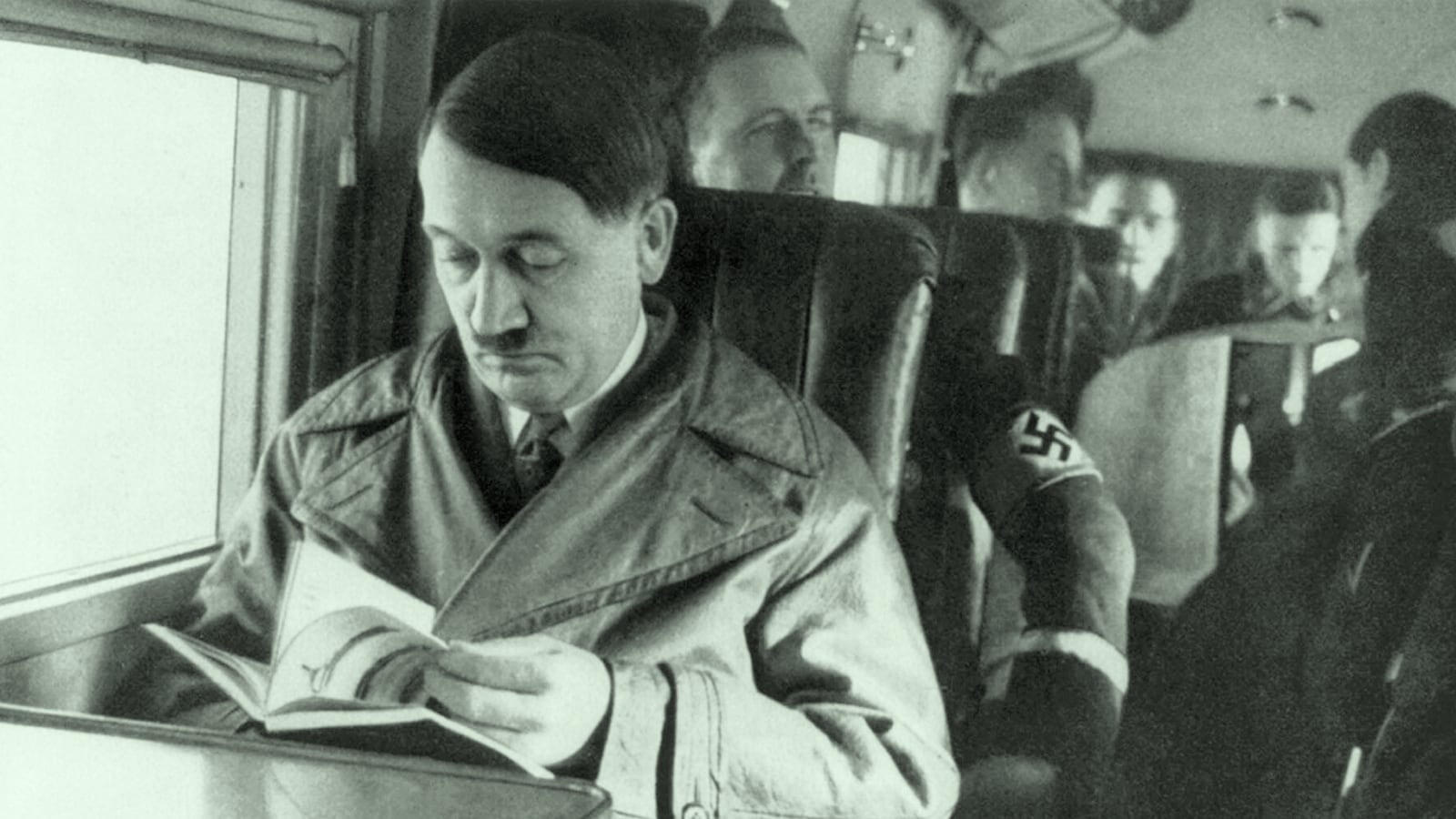

Behind the beer-hall polymath who bored for Deutschland lay a high-school dropout whose reading, in his Vienna flophouse years, consisted largely of gutter lit, apart from the odd bit of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer: “tracts on race theory, anti-Semitic pamphlets, treatises on the Teutons, on racial mysticism and eugenics, as well as popular treatments of Darwin and the philosophy of history,” as Joachim Fest put it in his definitive Hitler.

Written in an overwrought, pseudo-educated style, Mein Kampf screams intellectual insecurity from every page, its pretensions marred by tortured syntax, vulgarities, and mangled metaphors. Speaking of which, Hitler’s howler about the soul-crushing effects of poverty during his Vienna days is a perennial favorite with critics: “Whoever has not himself been on the tentacles of this throttling viper will never know its fangs.” Partei-poopers insist on pointing out that vipers don’t have tentacles and do not, in any event, throttle, and that anyone luckless enough to have the life squeezed out of him by a constrictor will never know its fangs because such snakes, unlike vipers, kill through asphyxiation, not envenomation.

Adolf besieged by grammar Nazis! It iss to laff, nein? But the laughter strangles when we read the chilling passages that prophesy the enslavement and slaughter of as many as 20 million human beings. As Kershaw notes, Hitler had been rousing the rabble for years with his ravings about the “racial tuberculosis” spread by that “causal agent, the Jew.” No one who read Mein Kampf with any care could have missed the marrow-freezing implications of statements like, “The nationalization of our masses will succeed only when, aside from all the positive struggle for the soul of our people, their internal poisoners are exterminated.” Mein Kampf may be the product of a world-class bore and semi-educated crank—the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper called it “a festering heap of refuse—old tins and dead vermin, ashes and eggshells and ordure—the intellectual detritus of centuries”—but its iron dream of a world purged of Jews and other “subhumans” came horrifyingly close to fulfillment, in the ovens and open-pit graves of the Holocaust.

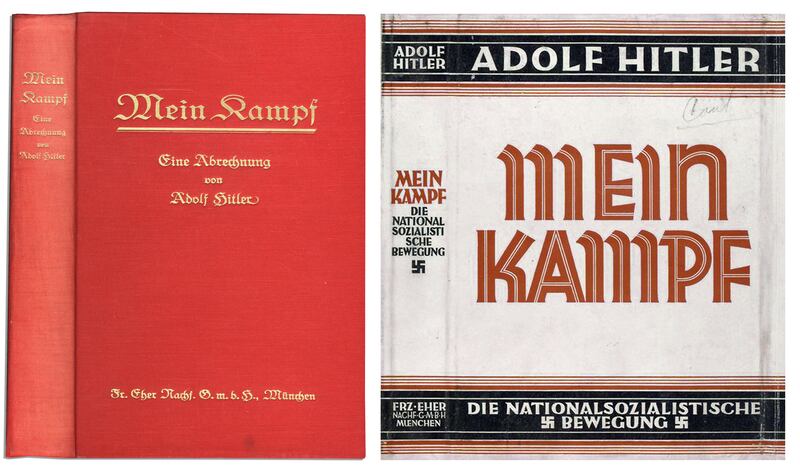

The idea behind Eine Kritische Edition, according to the Institute’s project leader, Christian Hartmann, was to “demythologize” the Satanic Bible of Nazism—to strip it of its mystique through historical scholarship. Even the Critical Edition’s austere packaging seems designed to demythologize: the slipcase is adorned with nothing but black-on-white type, marching around a gray rectangle; the two hardback volumes are bound in gray boards. The design recalls the poured-concrete Brutalism of Nazi architecture, the robot soldiers goose-stepping in formation, the grim functionalism of the concentration camps, the rigidity and repetition of Hitler’s thought.

If the editors and designer are hoping their visual rhetoric and scholarly commentary will serve as antidotes to the nastiest thing in the poison cabinet, they’re conducting a fascinating experiment. Can a critical perspective be woven into the warp and woof of a text? Can a book’s cover immunize us against its ideas, not matter how virulent? Eine Kritische Edition is selling briskly; the publisher has received orders for almost four times the initial print run of 4,000 copies. The Institute’s director, Andreas Wirsching, is confident the annotated edition “unmasks Hitler’s false allegations, his whitewashing, and outright lies.” But what if the reader is sympathetic to the book’s message? Won’t he dismiss the annotations whispering in his ear as the deceits of “international Jewry” or the nitpickings of the feckless professoriate, as Hitler would have?

The Third Reich is history’s best-branded atrocity exhibition, and Hitler—who gives over several pages in Mein Kampf to his role in designing the party’s notorious symbol—was its brand manager. Battle standards waving in torchlight, peaked caps and glistening jackboots, death’s-head insignias and zigzagging runes on black uniforms, and of course the supercharged logo of the Nazi terror, the swastika: these images still light up the switchboard of the mass unconscious. For those susceptible to the crude seductions of fascism, Mein Kampf borrows some of their dark glamour. It might be dull as one of those lunchtime monologues that bored Frau Goebbels cross-eyed, but such is the power of Nazi branding that Hitler’s book still casts a spell on a certain sort of reader.

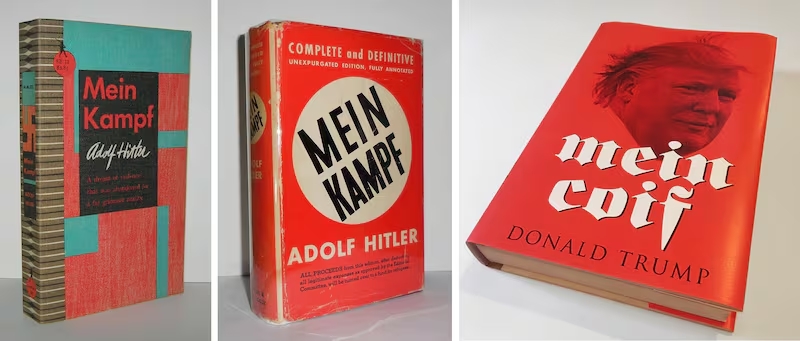

Immigrant-bashing xenophobia, racist nationalism, the mob mentality that doesn’t mind escorting protestors out of Trump rallies with a few cuffs and kicks, especially if they’re black: the fascist brand seems to be experiencing one of its periodic revivals, and little Hitlers in Europe and the U.S. are riding the wave of thuggish populism. (Did I mention that Greece’s neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party keeps its Athens bookstore well-stocked with copies of Mein Kampf? Or that it was the 11th best-selling book in India in 2015, its sales buoyed by the rising tide of Hindu nationalism whose pugnacious face is Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party? Modi’s India-for-Hindus-only demagoguery recalls Trump’s anti-Muslim blather. Speaking of whom, The People’s Choice—at least, among white working-class volk in search of a strongman and a scapegoat—reportedly keeps a copy of Hitler’s collected speeches, My New Order, by his bed.)

Maybe it’s time to fight branding with branding. I asked three acclaimed designers whether it might be possible to design a cover for Mein Kampf that strips it of its evil mystique, rebranding The World’s Most Dangerous Book as the biopsy of a diseased little mind.

Peter Mendelsund, the associate art director of Alfred A. Knopf, has relatives who survived the Holocaust, so there’s no chance in hell he’d design a cover for Hitler’s book (though he supports its publication on free-speech grounds). That said, if he were forced to—“gun to head,” he aptly puts it—he’d probably just use a photograph of some previous edition’s cover in order to create critical distance between us and the book; to force us to recall the role it played in historical events. “I’m suggesting that you treat the book as an artifact by photographing it,” he says. “It’s almost like looking at it under glass, in a museum vitrine. It historically contextualizes it.”

“The Nazis had a very effective approach to graphic design and propaganda,” notes Charles Brock, co-founder of the Bend, Oregon-based design firm Faceout Studio. “Picking up on that would be a good way to proceed. The [mere] sight of Hitler and a swastika make people uncomfortable, which would be a good thing when considering how to position this book ... My approach would be to push [the cover design] in a way that visually communicates the horrors of Hitler.”

Isaac Tobin, who is senior designer at the University of Chicago Press, agrees with Mendelsund that “the main challenge of designing Mein Kampf would be one of framing and contextualizing—making it clear that it is a repugnant piece of hate-speech that has value only as a record of the past, and not as the manifesto/rallying cry it was written as.”

Like Brock, he’s inclined to co-opt the visual language of the Third Reich, using its mesmeric power against it. “The Nazi party had such a strong visual language (one that is particularly appealing to graphic designers, with its white/black/red color scheme and strong geometric shapes) that it would be tempting to go in that direction,” he says.

Then again, “it would be all too easy to end up with a cover that acts like a continuation of the Nazi agenda, presenting Hitler’s text in a format he would recognize and approve of.” A better approach, he speculates, might be to embed the book in its historical context “in a very literal way—wrap the book with photos of the horrors perpetuated by Hitler.” He imagines using a “horrifying historic photo,” perhaps “a stack of corpses in a mass grave” or “records of Mengele’s experiments,” that “would make for an upsetting and disgusting cover that would match the true nature of the text within.”

Yet he worries that this design strategy, too, might backfire, “glamorizing and sensationalizing it in a different way different way: Mein Kampf as death metal album.”

In a sense, Mein Kampf’s cover is irrelevant. “The book is an advertisement for itself,” says Mendelsund. “The people that’ll be eager to buy it, whether as a historical document or to buy into its virulent anti-Semitism or horrific self-mythologizing, don’t need my help to understand what it is. No matter what I would do in terms of framing this thing visually, it will still be read and misread.”

Which brings us to a deeper, darker question: is it even possible, in these ideologically poisoned times, to change the mind of a true believer? Certainly, Hitler, a genius in the dark art of propaganda if nothing else, teaches us that minds can be changed. The bigotry, ignorance, and irrationality he unleashed were always there, to be sure, locked away in the mass unconscious, but Nazism let the German id off its chain. Hitler (and his sorcerer’s apprentice, the propaganda minister Josef Goebbels) turned one of the most literate, cultured countries in Europe into what the political scientist Daniel Goldhagen has called a nation of “willing executioners,” where ordinary citizens willingly, even gleefully joined in the fun of hunting down, torturing, and murdering Jews.

At a moment when the worst are full of passionate intensity and a Trump-ian contempt for “political correctness” is justification for the ugliest bigotry and the nastiest threats, the Enlightenment faith in the rational citizen, responsive to reason, looks a little naïve. An idea, as Morris Berman noted, is something you have; an ideology is something that has you.