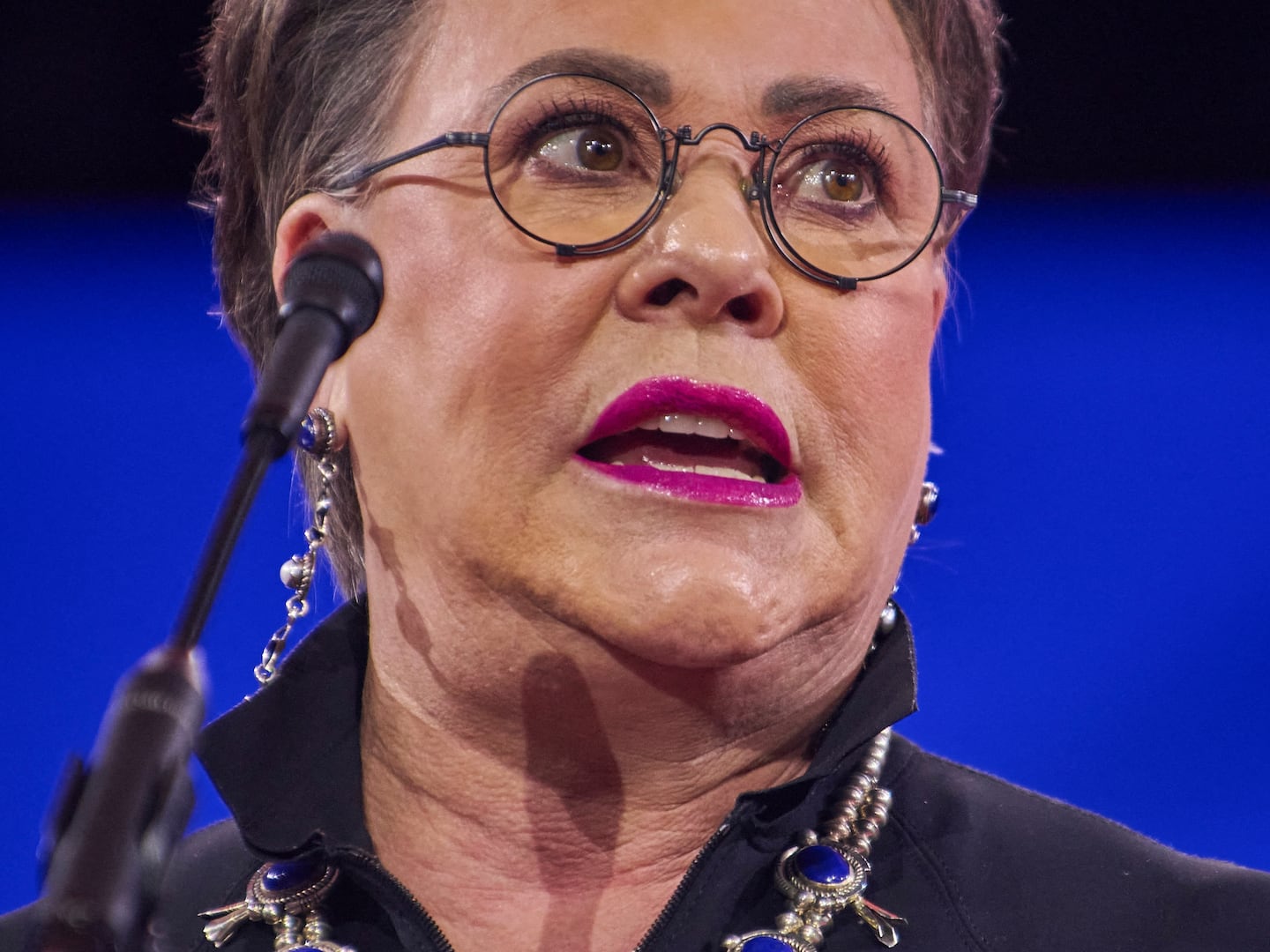

Journalist Maia Szalavitz has written about the intersection of drugs, policy, and the brain for more than two decades. In her latest book, Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, she chronicles her own experiences with these subjects, detailing how, at 23, she’d gone from having an Ivy League scholarship to shooting heroin and cocaine 40 times a day, getting busted for selling drugs, landing in jail, and finally in treatment.

But this book is more than an addiction memoir: it is also a guide to the neuroscience of addiction, and a primer for new thinking about how we view, prevent, and treat this growing problem.

What’s the main point you want to your book to make?

I want people to understand that addiction is a learning disorder. If you don’t learn that a drug helps you cope or make you feel good, you wouldn’t know what to crave. People fall in love with a substance or an activity, like gambling. Falling in love doesn’t harm your brain, but it does produce a unique type of learning that causes craving, alters choices and is really hard to forget.

It’s compulsive behavior that persists despite negative consequences. Once you realize that that’s the definition of addiction, you realize that what’s going on is a failure to respond to punishment. If punishment worked to stop addiction, addiction wouldn’t exist. People use despite their families getting mad at them, despite losing their jobs and being homeless. And yet we think the threat of jail is going to be different? Addiction persists despite negative consequences. That doesn’t mean that people don’t recover through coercive means, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best way to get there.

Addiction memoirs tend to follow common tropes: The writer got into trouble with a substance, couldn’t stop, experienced dreadful consequences, had an epiphany and is now better. Your book is very different.

My problem with addiction memoirs has always been that this is a deeply political problem and none of them have any political consciousness. They typically tell the story of sin and redemption, an individual story that can stand in for everyone else’s story. That’s just not true. I wanted to use my story to make a point about addiction that has gotten lost in this constant battle that we have: Is addiction a sinful choice or is it a chronic, progressive disease that must be treated with meetings and prayer? Both of those options have major flaws.

People who become addicted are wired differently, and it affects the manner in which they learn. We see people with addiction as valueless—literally, pieces of junk. But the interesting thing with different types of brain wiring is, they don’t bring only disadvantages. They can also bring advantages. Sometimes there are blessings hidden inside of curses. The compulsive drive that set me up for addiction probably also makes me a good journalist.

Having the ability to persist despite negative consequences is a plus in many ways. You could never parent or be in a relationship without that ability. Diaper-changing is not fun. There’s a lot of stuff in life where you just have to stick it out. When those same systems that give us motivation get misdirected toward a drug, that’s problematic. It doesn’t mean you’re broken, it just means you fell in love with the wrong thing.

I guess that’s where you break with the belief that addiction is a chronic, progressive brain disease.

Right. Many substances can harm your brain, but the point is, in terms of the changes we see in addictions, they’re much more like a form of learning than a progressive condition like Alzheimer’s. If addiction was genuinely a disease that got worse and worse, it should be harder to recover the older you get. But the data say differently: by their early thirties, half of people who have addiction, excepting tobacco, no longer meet diagnostic criteria. They learn to cut down on their own—and only 10 percent ever get treatment.

You are really careful about the language you use.

Language is power, and it’s important not to dehumanize people who have addiction. The term “addict” is stigmatizing and demonizing. The stereotype of the “addict” is also a stereotype we have for people of color. We have to move away from that language in order to move away from that racism.

Also, when we use the word “abuse,” it connotes really awful behavior, like domestic abuse, child abuse, sexual abuse. Nobody’s abusing a poor little drug. They might be misusing it, but they’re not abusing it.

And the very point of making something a crime is to stigmatize it. You want it to be stigmatized so people don’t do it. Yet you can’t say on one hand that you want to destigmatize addiction while you criminalize certain drugs. And the other thing that undermines the argument about addiction being a disease is that the only disease in America where 80 percent of the treatment is meeting, confession, and surrendering to a higher power.

Where do you stand on 12-step groups?

People find them useful and I’m not dissing them or saying that they should stop doing what works for them. My beef with the ideology is that it shouldn’t be part of treatment for which people are getting paid. Nobody should be paid for treatment that is basically indoctrination into a self-help group. There are two reasons why this is wrong. One of most important is: Why are we paying for what we can get for free? That’s not to say that a religious, spiritual, and moral framework isn’t often helpful to people with addiction. It is to say they shouldn’t be part of our medical system.

What helped you the most? I can’t really answer that because I don’t have an identical twin who did something else. Or at least several hundreds of them who also participated in a randomly controlled, double-blind trial. I did get some hope and social support through the 12 steps, and that’s critical. To recover, people need a sense of meaning and love and purpose. This is one of the reasons it’s so hard to put addiction into framework of disease. It’s also why it can seem like it’s a choice.

I went to a 28-day-place in Westchester after I got busted (for selling cocaine). If I were seeing myself as a patient today, I would have been on suboxone (an opioid replacement drug) and I don’t know if I would have stayed on it or not but I don’t think I’m any better or worse than anybody who stays on it. I was also living under the shadow and stress of the 15-to-life Rockefeller laws coming down on me. One day, I opened a CD and a packet of heroin fell out. Oddly the brand name was 7-to-Life, and I cried and just flushed it down the toilet. I had tons of cravings at first, but I could recall it in a good way and was able to let it go.

What hits me really hard is how incredibly lucky I was to be white, middle-class, and probably female. With my court case looming over me, I finally decided to get treatment. I went into treatment. I looked horribly scary and skinny. I weighed about 80 pounds and I had this horrible bleached blond hair. The judge I saw went easy on me and I’ll always be grateful, but she said the weirdest thing: “Let’s try to keep her out of jail. But she’s got to do something about that hair color.”

Even Donald Trump is calling for a change in the way we approach drug misuse. What’s your prescription?

We should decriminalize all drug possession, legalize marijuana, use the money we save to fund evidence-based treatment. We need to get rid of the cap on suboxone prescribers, (the law allows doctors to prescribe to only 100 patients) and use it as harm reduction as well as a path to recovery. We’d have fifty percent fewer deaths if we relied on medication-assisted therapy. People have to be alive to recover.