On Jan. 18, a small army of Georgia state troopers entered Atlanta’s Weelaunee forest, long guns drawn, to end a months-long occupation by a group of “forest defenders”—and to clear the way for the urban warfare training camp known as “Cop City.” Within minutes, an indigenous protester was dead, felled by a police bullet. Law enforcement sources claim the officer acted in self-defense, but witnesses say the deceased was unarmed.

It’s too soon to know what exactly went down, but however the facts shake out, Manuel Esteban Paez Terán joins a growing list of left-wing dissidents killed by police at (or near) protest events in recent years. And government intervention has only grown more deadly: the events of Jan. 18 marked the fourth such fatality nationally in the last three years.

Each death is different, but all share common threads. All of the protesters shot dead by law enforcement in the years since 2020 had been known, in their lifetimes, as outspoken critics of police violence.

Signs show the image of Manuel Teran, who was killed during a police raid inside Weelaunee People’s Park.

Cheney Orr/REUTERS/Cheney Orr/ReutersThere was Sean Monterrosa, 22, who was on his knees with his hands up when he was shot through the windshield of an unmarked Vallejo (CA) Police pickup truck in June 2020. Less than an hour before his death, he had been circulating a petition demanding justice for George Floyd.

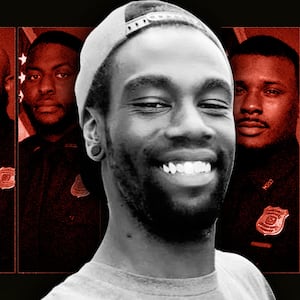

Michael Reinoehl, 48, and Winston “Boogie” Smith, Jr., 32, died in very different circumstances. Both were wanted men, loosely associated with “Antifa” and Black Lives Matter, respectively. They were effectively hunted, then gunned down by U.S. Marshals as part of their “task force” work in Minnesota and Washington state between late 2020 and early 2021.

Now yet another life has been lost, at the age of 26, to another militarized police force—a “multi-jurisdictional law enforcement task force charged with maintaining peace and security,” in the words of DeKalb County’s chief executive officer—amid circumstances that remain shrouded in mystery.

No body cams were turned on at the time. And Georgia’s Bureau of Investigation has reportedly rejected calls for an independent inquiry into the officer-involved shooting. Friends and family of the deceased feel it is they who are under investigation, as police munitions continue to fill the forests, the streets, and the squares of Atlanta with the smell of capsicum and the fog of war.

Anti-fascist activist Michael Reinoehl, who was shot dead by police in Washington State on Sept. 3, 2020. Above, Reinoehl protests against police violence and racial inequality, in Portland, Oregon, on July 18, 2020.

Mathieu Lewis-Rolland via ReutersThe right has less to fear from police violence than the left

One peer-reviewed study, “Policing Counter-Protest,” compared police responses to 64 protest events, left and right, between 2017 and 2018.

In Georgia and other southern states, the study’s author found police more likely to detain “those condemning Confederate statues than those protecting them,” and to arrest “anti-fascists than neo-Nazis.” But those regional trends mirrored national ones, too: The study found that “police disproportionately repress left-wing activists,” detaining more than 10 times as many left-wingers as right-wingers in a given year.

According to a much larger data set collected by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, while less than 6 percent of protests in 2020 saw the use of violence by antiracist demonstrators, at least 54 percent of police responses involved the use of force. Local, state, and federal agents were found to have used force three times more often on their left flank than on their right. Even in that subset of protests where no violence or vandalism was observed, leftist activists were three and a half times likelier to experience the use of force than their counterparts on the right.

Nowhere were the disparities starker than those protests involving large numbers of non-white participants—with the data showing police intervention occurred in nearly 10 percent of the more than 10,330 Black Lives Matter protests recorded in the second half of 2020, compared to just 4 percent of the estimated 2,350 “Patriot” protests over the same time period.

When right-wing, predominantly white Patriots have aimed their guns (or hired guns) at government officials, they have almost invariably been taken into custody—alive, and more or less unscathed. By contrast, the forest defenders in Atlanta have been left with the unmistakable sense that, in their own words, “the loss of our lives remains meaningless to the police.”

Their fellow activists say the death of Terán could mean one of two things: On the one hand, it could precipitate the beginning of the end of police militarization in Georgia’s “city in the forest.” On the other, it could mean that the training phase is now over—that a new era of urban warfare has, in fact, already commenced.

Why, then, do left-wing protesters keep getting killed by US police?

In any police-civilian encounter, in any moment of civil conflict, there is a clear logic of escalation that can lead from “less-lethal” to more lethal outcomes. There is almost always an alternative logic—that of strategic de-escalation—but as in other times and places since 2020, this has been the road decisively not taken in the Weelaunee forest.

The first step down this path of escalation: a chain of command which operates as if local and federal law enforcement is (or should be) at war with enemies of the state, real or imagined.

Agency leadership at the Atlanta Police Department (APD), the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and the Georgia Attorney General’s Office have repeatedly referred to the activists occupying the forest as “domestic terrorists” and/or “violent extremists.”

The APD’s second-in-command, Carven Tyus, explained the political considerations behind the “domestic terrorism” charges in a closed-door meeting with Atlanta’s Community Stakeholder Advisory Committee in 2022:

“It’s domestic terrorism because they all are terrorizing your neighborhood over there… They do not have a vested interest in this property… Why is an individual from Los Angeles, California concerned about a training facility being built in the state of Georgia? That is why we consider that domestic terrorism…”

“Can we prove they did it?” Tyus continued. “No. Do we know they did it? Yes.”

That seems to have been enough for the Georgia Bureau Investigation, according to the charging documents for alleged “domestic terrorists” this December. The documents show suspects are charged with “participating in actions as part of Defend the Atlanta Forest (DTAF), a group classified by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security as Domestic Violent Extremists.” Defendants “affirmed their cooperation with [DTAF],” in one case, by “being located on the property while wearing camouflage clothing,” and in another, by “occupying a tree house on the site, refusing to leave, and posting videos and calls for actions on social media sites.”

On Jan. 3, shortly after the first raft of terrorism charges was brought against forest defenders, Gov. Brian Kemp tweeted that “they will not be the last we will take down,” and that “the only response we will give is swift and exact justice,” before warning, ominously, “We will not hesitate, we will not rest, we will not waver in ending their activities.”

Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp speaks at a campaign event in Kennesaw, Georgia, U.S., Nov. 7, 2022.

Dustin Chambers/ReutersLess than three days after the killing of Terán, Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum joined the chorus calling for more terrorism charges and counterterrorism operations against protesters, while making the case for a whole new theory of broken windows: “It doesn’t take a rocket scientist or an attorney to tell you that breaking windows… that’s not protesting. That’s terrorism.”

Counterterrorism missions imply a militarized approach to public safety. They also call for a steady supply of military-grade weaponry.

From “non-lethal firing devices” to rocket-powered grenade launchers, high-powered rifles to Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles, the weapons of war continue to find their way into the arsenals of police departments like Atlanta’s (and state patrols like Georgia’s) by way of the 1033 program and related federal initiatives. Whatever police departments are unable to acquire through the government’s largesse, they are increasingly able to procure for themselves on the commercial market.

Rigorous social science research, using the 1033 program since 2014 as a proxy for militarization, has revealed that the more militarized the department, the higher the number of suspects killed by police in a given quarter.

Researchers also found that military materiel lends itself to quasi-military tactics and a paramilitary mindset, where suspects “become enemies that must be violently defeated and communities become foreign territories to occupy and subdue.”

The path to escalation has been paved, too, by a series of federal court rulings giving the police qualified immunity: a level of protection akin to a license to kill, whereby an officer involved in the death of a civilian is shielded from liability as long as they believed they were acting lawfully.

A protester is detained during demonstrations related to the death of Manuel Teran, who was killed during a police raid inside Weelaunee People’s Park in Atlanta, Georgia on Jan. 21, 2023.

Cheney Orr/ReutersBy contrast, civilians seeking a civil judgment face a seemingly insurmountable burden of proof. A wide-ranging analysis of appellate records from 2005 to 2020 showed the courts ruled in favor of the police, and against civilian plaintiffs, 57 percent of the time, and that they were 3.5 times more likely to accept a petition from a police officer than they were from a civilian.

Escalating battles for Cop City have been blamed on “outside agitators”—a familiar trope in the state of Georgia, historically used to refer to Black, Jewish, and other organizers who traveled to the south to fight for civil rights. Yet it would appear to be a group of inside agitators—drawn from the ranks of the Republican right and more liberal members of the donor class alike—who have been behind the political demand for a heavy hand against DTAF.

The media’s unethical double standards

The Atlanta Police Foundation (APF)—a public-private partnership aimed at lending “strategic support” to the APD—has been a leading backer of “the blue” in their battle against “the green” for the future of the Weelaunee forest. Flush with corporate donations from the likes of big banks like Wells Fargo, energy firms like Georgia Power, and retailers aligned with the Christian Right (such as Chik-fil-A and Home Depot), the APF has engaged in furious lobbying, political pressure tactics, and a public relations campaign by way of the city’s leading daily, all on behalf of Cop City.

Despite obvious conflicts of interest, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution has taken to parroting right-wing talking points in its protest coverage, claiming to have unearthed “a seemingly well-coordinated but nebulous group that includes police abolitionists, environmental extremists, and anarchists… responsible for a growing list of aggressive, sometimes violent actions.”

A who’s who of right-wing “news” outlets have since joined the AJC on the warpath.

Some of the headlines: “How Stop Cop City Movement Led to Violent Night in Downtown” (Fox 5 Atlanta). “This Isn’t Protest. This Is Terrorism: Five Antifa Extremists… Pulled Down from their Treehouses” (The Blaze). “Spoiled Children of Privilege Trying to Burn Atlanta Down” (Andy Ngo). “Kids... Are Turning into Violent Antifa Monsters” (Tucker Carlson).

What we are seeing, in the wake of the latest police killing, is not only the de-platforming of left-wing protesters, but also the re-platforming of far-right provocateurs, with their tales of paid protesters and crisis actors, of shadowy conspiracies and domestic terror plots.

The public is correct to be concerned with growing violence in our streets. But those seeking to cast blame on antiracist, antifascist, and environmentalist activists are barking up the wrong tree.

This media environment has undoubtedly contributed to an atmosphere of cruelty and permissiveness. But more and more, it is police violence against protesters that is deemed permissible, with calls growing in some quarters for an even heavier hand. Meanwhile, the casualties keep coming, with no letup in sight: dozens more dissidents have been injured by baton blows, tasers, tear gas, pepper pellets, rubber bullets, and other pain compliance methods since 2022. Just last week, another protester was hit by a police car in the streets of Atlanta.

For many “forest defenders,” the risk of death now comes with the territory—but so, too, does the prospect of new life, springing from the forest floor among the ruins of their months-long occupation.

Manuel Terán seemed to understand this at a visceral level: “Am I scared of the state?” they could be heard wondering aloud shortly before their passing. “Pretty silly not to be. I’m a brown person. I might be killed by the police… But you can’t let the fear stop you from doing things: from living, from existing, from resisting.”