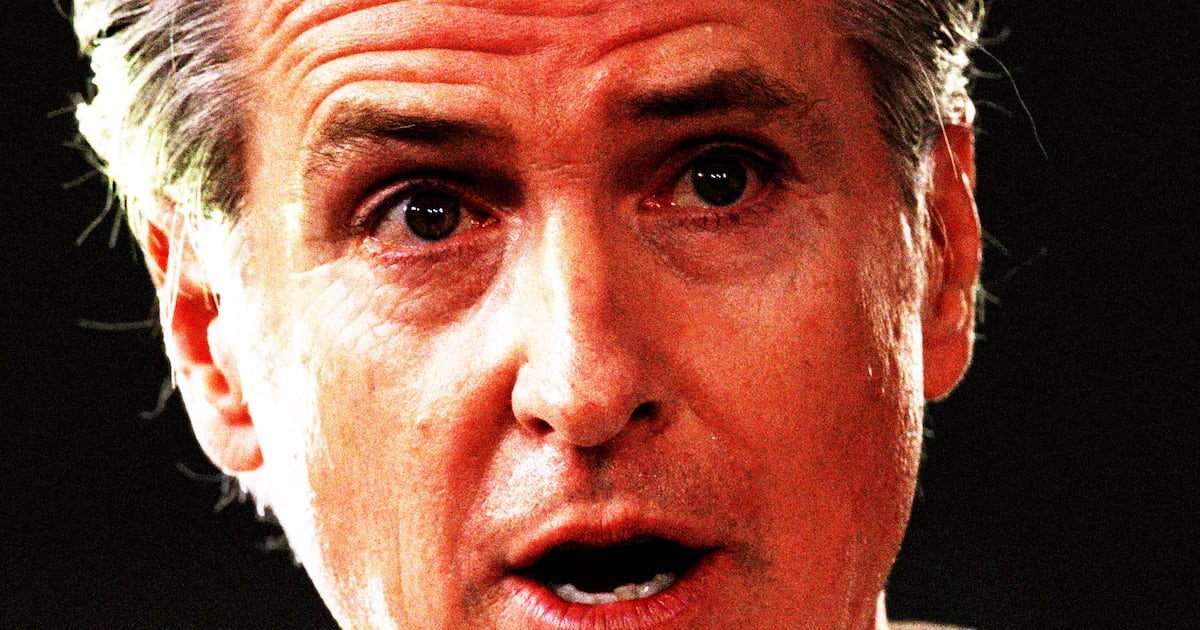

If media reports are true, Barack Obama will soon nominate Chuck Hagel to be secretary of defense. If so, it may prove the most consequential foreign-policy appointment of his presidency. Because the struggle over Hagel is a struggle over whether Obama can change the terms of foreign-policy debate.

Understanding what that means requires understanding the state of foreign-policy discourse in the two parties today. First, the GOP. Had a Martian descended to earth in January 2003, spent a few days listening to Washington Republicans talk foreign policy, and then returned in January 2013, she would likely conclude that the Iraq War had been a fabulous success. She would conclude that because, as far as I can tell, not a single Republican-aligned Beltway foreign-policy politician or pundit enjoys less prominence than he did a decade ago because he supported the Iraq War, and not a single one enjoys more prominence because he opposed it. From Bill Kristol to Charles Krauthammer to John McCain to John Bolton to Dan Senor, the same people who dominated Republican foreign-policy discourse a decade ago still dominate it today, and they espouse exactly the same view of the world. As for those conservatives who opposed Iraq—people at places like the Cato Institute and The National Interest who believe that there are clear limits to American military power—our Fox News–watching, Wall Street Journal–reading Martian would have been largely unaware of their existence in 2003 and would remain largely unaware today. Our Martian friend might know somewhat more about Ron Paul than she would have a decade ago. But that familiarity would consist largely of the knowledge that respectable Republicans consider Paul a nut.

As intellectual history, this is astonishing. When Democrats took America into Vietnam, protesters rioted in the streets at the party’s 1968 convention. Academics like McGeorge Bundy and Walt Rostow became such pariahs after serving in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations that they could not return to their old universities. Prominent pro-war columnists like Joseph Alsop became laughingstocks. Former Vietnam hawks like Zbigniew Brzezinski had to intellectually reinvent themselves to secure government jobs when the Democrats returned to power under Jimmy Carter. The Iraq-era GOP, by contrast, has constructed an intellectual cocoon so hermetically sealed that it has remained uncontaminated by the greatest foreign-policy disaster of the past 30 years. That’s partly the result of the “surge,” which allowed the Republican foreign-policy establishment to claim, in my view incorrectly, some measure of vindication. It’s partly because Iraq required no draft, and thus ordinary Americans never mobilized as dramatically to oppose it, which allowed foreign-policy elites to remain more insulated from shifts in the public mood. It’s partly because the institutions where conservative foreign-policy types work—places like The Weekly Standard, Fox News, and the American Enterprise Institute—have no natural mechanism for reconsidering their view of the world. When Vietnam went south, the intellectual climate at Harvard (where Bundy served as a dean) and The New York Times (which had initially backed the war) changed because Harvard and The New York Times had missions that transcended any particular perspective on American foreign policy. By contrast, hawkish nationalism is so intrinsic to the identity of places like Fox, the Standard, and AEI that abandoning it would threaten their reason for existence.

The final reason for the resiliency of this Republican foreign-policy cocoon is the American media, especially the television media, which take an entirely à la carte view of foreign-policy debates. Rarely is anything a commentator or legislator said yesterday about war with Iraq or Afghanistan deemed relevant to his or her credibility today on the subject of war with Iran. On cable, you shake an Etch a Sketch every time you go on air. Thus, the same Republican commentators and politicians who pushed a hawkish line on Iraq moved seamlessly to pushing a hawkish line on Afghanistan, and once that too became a lost cause, to pushing a hawkish line on Iran and everything else.

That hawkish line consists of hostility to any diplomatic solution to the Iranian nuclear standoff that involves meaningful American compromise and cautious optimism about the impact of an American military strike. More generally, it means supporting as large a defense budget as possible, irrespective of its impact on America’s fiscal health. This is the perspective that Republican foreign-policy pundits call “mainstream” and from which they say Hagel diverges. And they are right. Taking a hawkish line on Iran and military spending is as mainstream in today’s GOP as was taking a hawkish line on Iraq and Afghanistan between 2001 and 2003, because Republican Washington has created an ecosystem in which the wisdom of that prior hawkishness is irrelevant to contemporary debates.

What makes Hagel so important, and so threatening to the Republican foreign-policy elite, is that he is one of the few prominent Republican-aligned politicians and commentators (George Will and Francis Fukuyama are others, but such voices are rare) who was intellectually changed by Iraq. And Hagel was changed, in large measure, because he bore within him intellectual (and physical) scar tissue from Vietnam. As my former colleague John Judis captured brilliantly in a 2007 New Republic profile, the Iraq War sparked something visceral in Hagel, as the former Vietnam rifleman realized that, once again, detached and self-interested elites were sending working-class kids like himself to die in a war they couldn’t honestly defend. It is certainly true that some politicians who served in Vietnam—for instance, John McCain—did not react to Iraq that way. But it is also true that the fact that so few American politicians and pundits lived the kind of wartime hell Hagel endured made it easier for them to pass through the Iraq years unscathed. It’s no coincidence that the other senator most deeply enraged by Iraq was ex-Marine James Webb, another former hawkish Republican who saw the war through his own personal Vietnam prism.

At the heart of the opposition to Hagel is the fear that he will do what Republicans have thus far largely prevented: bring America’s experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan into the Iran debate. Much of the Republican and establishment Jewish criticism of Hagel centers on his comments about the “Jewish lobby.” Some critics genuinely consider those comments offensive (though I don’t). But ultimately, Hagel’s “Jewish lobby” remarks are a sideshow. Were he as hawkish on Iran as McCain is, Republican senators, conservative journalists, and American Jewish officials would almost certainly have overlooked them, as they largely overlooked (or outright defended) the more problematic recent comments about Jewish media ownership by Rupert Murdoch. The bald truth is that for many conservatives today, the key test of how someone feels about Jews is whether they support Israel’s security needs, as conservatives define them. Had Hagel passed that test, conservative Republicans and Jewish “leaders” would be as bothered by his use of the term “Jewish lobby” in 2005 as they were when Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations executive vice chairman Malcolm Hoenlein used the phrase last month. Which is to say, not at all.

My point is not that because the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have proved disastrous, war with Iran would too. Every war is different, and I wrote a whole book about how difficult it is to predict, on the basis of one conflict, how the next will turn out. But a Hagel nomination will ensure that when Obama officials discuss a third Middle Eastern war, the ghosts of Iraq and Afghanistan sit at the table. And while that won’t make American military action impossible, it will raise the bar.

What the Republican foreign-policy establishment fears is that with Hagel as secretary of defense, it will be impossible for Obama to minimize the dangers of war with Iran, as George W. Bush minimized the dangers of war with Iraq. Hagel would be to the Obama administration what Dwight Eisenhower was in the 1950s, what Colin Powell was in the 1990s, and what, to some degree, ex-Mossad head Meir Dagan was in the Netanyahu government, the military man who bluntly reminds his colleagues that war, once unleashed, cannot be easily controlled. “Once you start” a war with Iran, Hagel told the Atlantic Council in 2010, “you’d better be prepared to find 100,000 troops, because it may take that.” You can’t say “it’ll be a limited warfare. I don’t think any nation can ever go into it that way.” For Hagel’s ex-friends in the Republican foreign-policy class, such a statement is kryptonite, because they know that given the American public’s weariness of war, a president who outlined the risks that way would have trouble gaining popular support. It’s also likely that Hagel’s position would be reinforced by the leaders of the uniformed military, some of whom have already expressed skepticism about bombing Iran.

More generally, Hagel’s Republican critics realize that Iraq has changed his view of American power. To call Hagel an isolationist is silly. Unlike Pat Buchanan or Ron Paul, he is enthusiastic about international institutions and foreign aid. But Iraq and Afghanistan have convinced Hagel that boosting American military spending, and extending America’s global military footprint, can weaken national security if they drive America deeper into debt. Like his hero, Eisenhower, who slashed defense spending because, according to his Treasury secretary, he “feared deficits almost more than he feared the communists,” Hagel believes the defense budget must “be pared down,” because he refuses to divorce the conversation about military spending from the conversation about fiscal solvency. Unlike the Republican foreign-policy elite who for eight years cheered as the Bush administration charged its expansive “war on terror” to the nation’s credit card, Hagel does not view substantial cuts to the Bush-era defense budget as a retreat from American global power. To the contrary, he views them as essential to restoring the economic strength that must undergird that power. In that way as well, Hagel’s insistence on learning the lessons of the past 10 years would threaten the historical amnesia that governs Republican foreign policy.

But that’s only half the story. Understanding why Hagel’s nomination could change the terms of foreign-policy debate also requires understanding the state of foreign-policy discourse in the Democratic Party. If the defining characteristic of Republican foreign-policy discourse in Washington today is amnesia, the defining Democratic characteristic is timidity. And Hagel would challenge that as well.

In the Democratic Party today, ascending to a top foreign-policy job is like ascending to a federal judgeship: the less you say that anyone could possibly disagree with, the better your chances. Partly, this is a residue of the hoary, and still extant, Democratic fear of being deemed insufficiently tough by the Republican right. During the Bush years, I attended some brainstorming sessions convened by Democratic-leaning think thanks and foundations aimed at rethinking party foreign policy, and what struck me was the degree to which Fox News had gotten inside people’s heads. It was virtually impossible to have a blue-sky conversation about, for instance, how seriously people took the threat from Al Qaeda terror, or whether they believed it possible to deter a nuclear Iran, without the conversation getting sidetracked by a discussion of whether even entertaining such questions was politically viable.

In recent years, as the GOP’s post-Vietnam foreign-policy advantage has disappeared, Democratic fears of right-wing attack have eased somewhat. But the habits of caution, and the bias against provocative and independent thought, remains. Consider the fate of Kenneth Pollack and Michael O’Hanlon, two Brookings Institution scholars once considered top contenders for senior foreign-policy jobs in a Democratic administration. Instead, both men have remained at Brookings while their contemporaries cycle in and out of government. The reason? Pollack and O’Hanlon vocally supported invading Iraq, the former in a readable and influential book and the latter in a blunt interview with Bill O’Reilly on Fox. That might make sense had the people who beat Pollack and O’Hanlon out for top jobs been vocal Iraq War opponents. But for the most part, Pollack and O’Hanlon were bested not by people who clearly opposed invading Iraq but by people who took no clear public position one way or another. That’s true of U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice, who conducted four interviews with National Public Radio in the six months leading up to the war in which she made many sage comments but never revealed whether she supported the invasion. And it’s true of Hagel’s competitor for secretary of defense, Michèle Flournoy, a smart, well-qualified, decent woman who on March 4, 2003—15 days before the war began—conducted an online chat about Iraq with The Washington Post. I defy anyone to read it and determine whether she supported the war.

When Obama won the presidency, some hoped that his example might alter this culture of caution. Obama had defeated Hillary Clinton, after all, in part because he made the risky decision to publicly oppose the Iraq War at a time when most other Democratic politicians were either supporting it or keeping their heads down. Early in the presidential campaign, Obama had also made unusually candid statements about Israel, noting that discussions of Israeli policy were “much more open ... in Israel than they are sometimes here in the United States” and that “there is a strain within the pro-Israel community that says unless you adopt an unwavering pro-Likud approach to Israel that you’re anti-Israel.”

But ironically, the dynamic proved almost exactly the opposite. Precisely because Obama, from the very beginning, was considered vaguely edgy on foreign policy, he surrounded himself with advisers who gave him political cover. Thus, during the 2008 general election campaign, Obama made Dennis Ross, the Democratic Mideast hand most trusted by the “pro-Israel” right, his main spokesman on the issue rather than Daniel Kurtzer, who had endorsed Obama earlier but whose frank opposition to settlement growth as ambassador to Israel had made him less trusted in Jewish establishment circles. Or consider the Obama campaign’s treatment of former Clinton-administration national-security staffer Rob Malley. After leaving office, Malley had co-written a controversial essay arguing that Yasser Arafat was not solely to blame for the failure of the 2000 Camp David peace talks and met (as a private citizen) with representatives of Hamas. In response, an Obama campaign aide privately pledged that Malley would not receive an administration job, and the campaign distributed an article by my old TNR boss Marty Peretz that praised Obama while calling Malley “a rabid hater of Israel.” Malley discovered what the campaign had done when the mass email containing Peretz’s article arrived in his inbox.

This pattern of surrounding himself with advisers more cautious than himself continued once Obama took office. He made Hillary Clinton—the woman whose foreign-policy views he had derided as cautious and conventional during the campaign—his secretary of state. As national-security advisor he chose James Jones, a man who had twice been offered the job of deputy secretary of state in the Bush administration. At the Pentagon he kept on the Bush administration’s Robert Gates. A month into Obama’s presidency, when Director of National Intelligence Dennis Blair selected Chas Freeman to head the National Intelligence Council, Freeman quickly came under attack, largely for a series of comments about Israeli policy that, while harshly critical, would not have been out of place in Haaretz. After two weeks without any show of support from the White House, Freeman withdrew his nomination.

Partly as a result of these personnel decisions, Obama’s foreign policy—while often operationally skillful—has left unchallenged many of the assumptions made “mainstream” by George W. Bush. Obama has never questioned Bush’s insistence that Iran cannot be deterred, even though deterrence was crucial to America’s strategy against China and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. He has abandoned his promise to close Guantánamo Bay. And during the debate over the Afghan surge, when Obama grew skeptical of David Petraeus’s push for 40,000 new troops, his top cabinet secretaries constrained rather than encouraged his heretical thoughts. In his book Obama’s Wars, Bob Woodward reports that Hillary Clinton, along with Robert Gates, played a key role in “diminishing the president’s running room. She had reduced his cover for any decision with significantly fewer troops.”

All of which makes the Hagel pick so important. Unlike John Kerry, whose political caution has smoothed the way for a virtually uncontested secretary-of-state nomination, Hagel says in public what others only say in private. In his 2005 book, The Much Too Promised Land, former Clinton administration Middle East hand Aaron Miller notes that “of all my conversations [about the Israel debate in Congress], the one with Hagel stands apart for its honesty and clarity.” That’s because when Hagel told Miller that “the Jewish lobby intimidates a lot of people up here,” he was saying the same thing that people who work in Congress and the executive branch say all the time. As Thomas Friedman has noted, “I am certain that the vast majority of U.S. senators and policy makers quietly believe exactly what Hagel believes on Israel.” But the operative word is quietly. I’ve also heard many government officials, some of them Jewish, say things similar to what Hagel is now being flayed for having told Miller. The difference is that those other officials first confirmed that they were speaking off the record. One even lowered his voice and closed the door.

Hagel’s uncommon honesty isn’t restricted to Israel. Among the statements that critics now decry is Hagel’s 2007 declaration that “People say we’re not fighting for oil [in Iraq]. Of course we are.” In The Weekly Standard, Bill Kristol calls Hagel’s statement “vulgar and disgusting.” What Kristol doesn’t note is that the same article that quotes Hagel also quotes noted radical Alan Greenspan saying virtually the same thing. The difference: Greenspan said it in his memoir, published once he was safely retired from government service.

As John Judis notes, Hagel was considered a plausible Republican presidential candidate in 2008 until his blunt criticism of the Bush administration’s Iraq policies ended his career in the GOP. He is, therefore, one of the very few public figures in recent memory—Joe Lieberman, whose blunt support for the Bush administration’s Iraq policies ended his career in the Democratic Party, is another—to have forfeited a national role in his political party because of his policy views. In the process, Hagel has incurred the wrath of the same hawkish “pro-Israel” forces whose influence he was rash enough to acknowledge. He has done, in short, exactly what people who aspire to jobs like secretary of defense in Democratic administrations learn not to do. If Barack Obama nominates him anyway, it will be the greatest blow in years to the culture of timidity that dominates the Democratic foreign-policy class. As one former Obama administration official puts it, “Before, when 25-year-olds came to me for career advice, I would tell them, ‘You should be very circumspect, very cautious.’ After Hagel, I would say it’s OK to have strong, even divisive opinions.”

Barack Obama has been commander in chief for nearly four years, but in important ways, the Obama era in American foreign policy has not yet begun. It will begin when Democrats express their foreign-policy views as fearlessly as do their Republican counterparts and when those Republican counterparts can no longer impose their historical amnesia about the catastrophes of the last 10 years on public debate. It will begin when the American right can no longer marginalize public officials with whom it disagrees about Iran by hurling charges of anti-Semitism with a promiscuity that would make Al Sharpton blush. It will begin when Obama surrounds himself with advisers more interested in shifting the foreign-policy “mainstream” than parroting it. It will begin when Obama declares independence from the Bush-era assumptions that have so far constrained his foreign policy. And with luck, we will one day look back upon Chuck Hagel’s nomination as the day it did.