“I’m reading Proust”: for months I’ve been saying this to myself in front of the mirror. When asked about what I’ve been up to in lockdown, I drop the phrase nonchalantly, as though A La Recherche du Temps Perdu were just any old 200-page potboiler and not the massive, life-altering undertaking it is. I’m playing it cool, but the reaction I’m hoping for is raised eyebrows followed by a notable improvement in my friends’ opinion of my intellectual prowess.

(“I’m re-reading Proust” would be even cooler—but despite a university degree that saw me happily hoovering up Dostoyevsky and George Eliot, I had always been scared off by this loftiest of literary summits. Until now.)

My Marcel mania was born in the first lockdown, that strange, sunlit time when it seemed desirable to be engaged in a Project. I’d already watched the whole of The Sopranos on HBO, knitted my own sourdough, and been impressed by a man on YouTube who’d made a kitchen workstation entirely out of pallets. I was about to order a boxful of contemporary novels on Amazon when my purchase was halted in mid-click. What about my commitment to recycling and reusing? Whither my rejection of nakedly consumerist habits like, well, ordering a load of new stuff on Amazon?

Instead I would choose, from my own library, a classic Big Novel I’d hitherto shirked. Which was it to be? Richardson’s Clarissa, the monumental and borderline-unreadable 18th-century epistolary novel? War and Peace? Too much of an easy read. Finnegans Wake? Too much like hard work. The tome in question would need the heft to see me through what might turn out to be months of confinement, the advantage being I’d need no other reading-matter for the duration. What better than Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, a pillar of Western culture which, like the Bible, only the truest believers can claim to have read in its entirety?

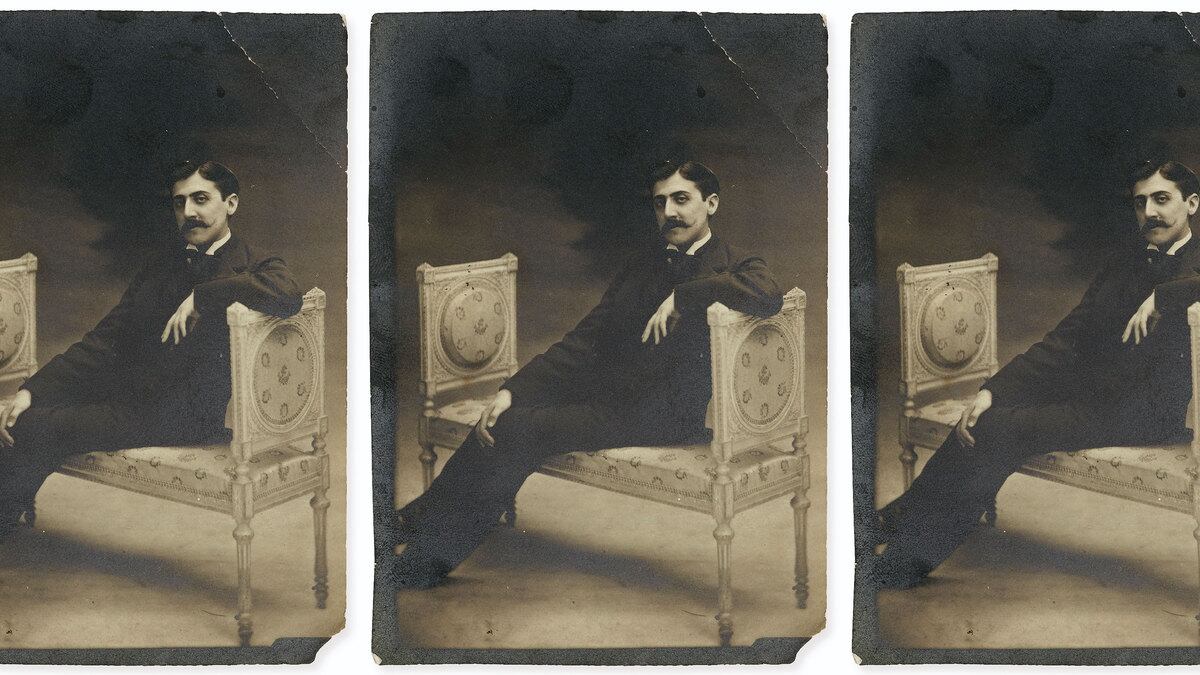

As it happens, Proust is currently having a bit of a moment. Not only does next year mark the centenary of the great man’s death, but just last week, with auspicious timing, French publisher Gallimard announced the rediscovery of an early work thought to be the germ of A La Recherche du Temps Perdu. The long-lost manuscript, known as The Seventy-Five Pages, is described excitedly as a “logbook of his creation” and an “essential piece of the puzzle” providing access to “the primitive Proustian crypt.”

I found a three-volume paperback edition of C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation, each of the volumes a doorstop of 1000+ pages, unloved and unread among the byways of my bookshelves. Inscribed on the title page was a message from my aunt Lesley on the occasion of my birthday in 1984. Volume One had barely-legible margin scribbles in my own handwriting, but they fizzled out after a hundred pages.

Under normal circumstances, most readings of A La Recherche do tend to fizzle out. But in the entirely abnormal situation in which we find ourselves, Proust just might be the perfect companion. For one thing, the novelist was the son of an epidemiologist. For another, he was a master of social distancing. Following the death of his mother in 1905, Proust spent six weeks in semi-isolation at neuropsychologist Paul Sollier’s clinic at Boulogne-sur-Seine. Four years later he ensconced himself in his rooms at 102 Boulevard Haussmann, whose cork-lined walls had the effect of insulating him, not just from the dust and noise that aggravated his respiratory condition, but from the outside world in general: a shielding avant la lettre.

If my reason for not reading Lost Time had always been a lack of time, that excuse was no longer valid. I noted the remark made by Proust’s younger brother Robert, also a medic, to the effect that you’d have to break a leg, or be in the grip of a long-drawn-out illness, to find time for Marcel’s novel. He might have added “in the throes of a global pandemic.” If I was ever going to tackle this craggy Everest of world literature, the moment was now.

Halfway through April, as the virus ravaged Europe, I settled into an armchair and spoke aloud the famous opening sentence (“For a long time I used to go to bed early.”) Nine months later, a few hundred pages still separate me from the final sentence of Time Regained (“…if strength were granted me for long enough to accomplish my work, I should not fail…”) but at least I can see, like Proust himself, that there’s light at the end of the tunnel.

I’ll admit the going was hard at first. Proust’s prolixity and preciousness were nearly unbearable, and I swam feebly among the swirling currents of his sentences—the longest of which is said to extend to over 1,000 words. My husband got used to my exasperated cries of “get on with it, man!” from the depths of the sofa. Few novels make such demands on the reader. Proust offers nothing like the easy satisfaction of finishing a chapter, and there are few resting-places on the way to the summit. At times I felt a wistfulness shading into panic: Would I ever emerge from this stifling bourgeois milieu, this boundless sea of logorrhea?

Then, sentence by sentence, page by page, I fell under the spell. I learned to relish the juicy bits, the flashes of wit and Dickensian comedy, which compensate for the occasional longueurs. Now I was firmly on track, I could forgive even Proust’s obsessive gnawing over the same eternal themes of jealousy, memory, and perception. The high-society party scenes of The Guermantes Way with their mind-numbing tittle-tattle over hundreds of pages, like Jane Austen on Valium, reminded me of the battle scenes in War and Peace or the relentless and harrowing femicides in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666: It was tempting to skip them, but they came to have a hypnotic power of their own.

During the first lockdown I carried the book with me everywhere, literally and metaphorically. The sheer weight of it caused a bothersome ache, an unusual kind of RSI, in the bones of my right hand. (If there were ever an argument for e-books this would be it—yet to read Proust on Kindle would mean losing the element of heroism involved in ploughing through 3,294 pages of actual print.) The ancient glue on the paperback spine soon came unstuck, breaking into chunks that were themselves the size of a standard 300-page novel.

The mesmeric rhythm of the writing wormed its way into my brain. On hot summer days I would take up the book after lunch, drift through a couple of pages and promptly sink into a long siesta. In my dreams I was hanging out with Albertine, Andrée, and the girls on the promenade at Balbec, or delivering stinging ripostes to the bitch-queen Baron de Charlus. Robert de Saint-Loup, surely one of the most lovable characters in all literature, became my fantasy best friend.

A La Recherche was unlike any reading experience I’d had before. It required, not only steely reserves of concentration and the mental agility to navigate the author’s endlessly spooling subordinate clauses, but also a particular attitude of mind, a willingness to give up the struggle and be swept away in the onrush of words.

“So what’s it all about, then? And what actually happens in the book?” You may well ask, but these are questions a Proust fan dreads having to answer. It reminds me of the old Monty Python sketch in which contestants on a cheesy TV game show are challenged to “summarize Proust’s masterwork once in a swimsuit, and once in evening dress”—the punchline, of course, being that they barely scratch the surface and the prize ends up going to “the girl with the biggest tits.”

Still, here goes: The story, told anonymously in the first person, is of a young man and his awkward progress toward emotional and creative maturity. The plot, such as it is, turns on a series of key locations: a country house in a Normandy village (scene of the famous lime-tea-and-madeleine episode that becomes the foundation stone for the novel’s vast edifice of memory), an apartment in an aristocratic quartier of Paris, and a grand hotel in a seaside town. Love in all its variegated forms and its complication by jealousy and mistrust, lies, and lust—here is the book’s great overarching theme, played out in the passions of Swann and Odette, of Charlus and Morel, and in the narrator’s tempestuous relationships with Gilberte and, later, with the traitor Albertine.

There is philosophy in there, comedy and poetry, scandals political and sexual, not to mention plenty of salacious gossip. The pleasures to be had are many and various. Myself, I love to stumble on one of Proust’s brilliant aperçus like a shiny pebble in the bed of a stream, or a luminously beautiful piece of description. Remembering one of his night-time walks with Gilberte, the narrator notes in passing: “Before descending into the mystery of a deep and flawless valley carpeted with moonlight, we stopped for a moment like two insects about to plunge into the blue calyx of a flower.”

Beneath the society chatter and the high-flown rhetoric lies a vein of deep emotion. The death of Albertine in The Fugitive brings on a flood of anguish that’s heartbreaking to read. As the story rolls round to a close and the characters die off one by one, the narrator’s hard-won acceptance of his destiny as a writer is profoundly affecting. Latterly there have been tears, as well as complaints, from the depths of my sofa.

To be sure, there are things about the novel to puzzle and/or repel. The snobbery and anti-Semitism that interleave the narrative are frankly horrifying. Proust’s flat-out refusal to address his own homosexuality, the narrator being portrayed instead as a red-blooded lover of women, I found depressing. The payoff lay in the poetic loveliness of Proust’s descriptions of the sea and the moods of nature, and also in his razor-sharp comic sense and rapier wit. Among other things A La Recherche is literature’s greatest paean to procrastination, a gigantic preamble to the moment in the final pages when (spoiler alert) the narrator finally picks up his pen to begin writing the book that you have just spent months of your life reading.

Like the best TV series, Proust draws you in slowly and keeps you there, yet however assiduously you binge-read, it seems you’ll never be short of new episodes, new seasons. In terms of sheer entertainment value for a modest outlay, Proust is priceless.

Would I do it again? If this goes on much longer, I might have to. Next time round I’ll know to linger on the seascapes of Balbec and the scent of white hawthorn on the paths around Combray. I’ll have a pencil in hand to note down the sparkling gems of Proustian wit. Then, when the centenary comes round next year I can smugly say I’ve already done my homework. Come to think of it, there’s a lockdown project that might just impress my friends even more than “I’m reading Proust”: “I’m reading Proust in French.”