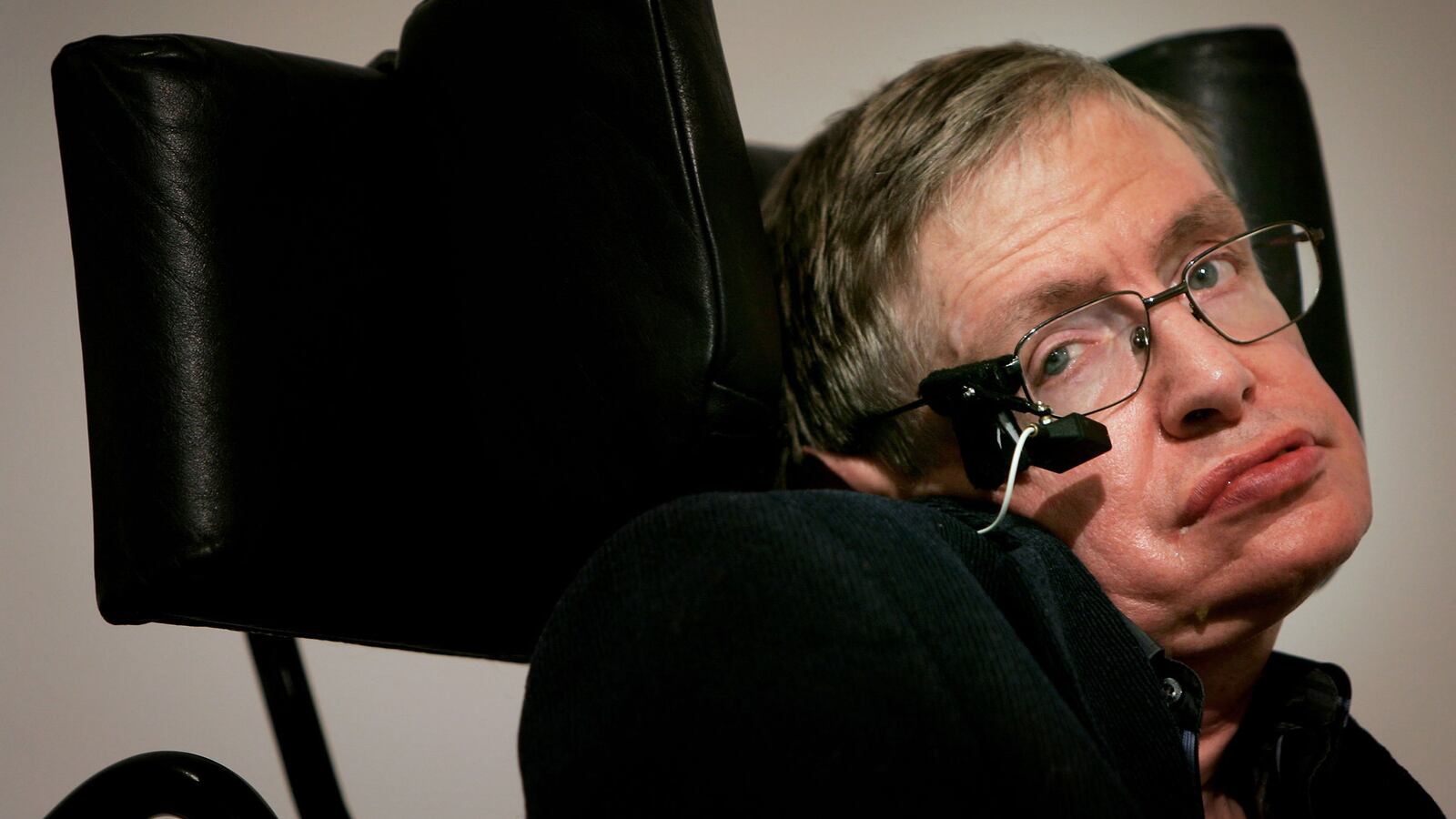

On Wednesday, British physicist Stephen Hawking died after a decades-long battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. He was 76—beating an initial diagnosis in 1963 at age 21 that suggested he’d be dead within a few years.

But oh, how he lived.

Hawking was arguably the most recognizable modern scientist, thanks to a perfect storm of pop culture resonance and scientific achievement. His whirling around his wheelchair was immortalized in such geek fandoms with appearances in The Simpsons and Star Trek. Then there was a little Hollywood flick starring Eddie Redmayne as Hawking, The Theory of Everything, that further cemented Hawking’s reputation into the public’s imagination as the epitome of physics and science.

But Hawking’s initial claim to fame was rooted in the very birth and death of our cosmos. Hawking’s thesis on black holes and the expansion of the universe made him think about how the universe developed in the first place, and how it would theoretically end. Hawking’s proposal of the universe starting with a Big Bang and ending in a Big Crunch, folding in his rumination that black holes emitted heat and radiation and pushing Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity forward with quantum mechanics, created waves within the otherwise sleepy physics community, questioning what we knew of our past and suggesting a future that no one had dared to think about.

The book that catapulted him to fame, A Brief History of Time, was one of the first to make the notoriously difficult subject of physics more accessible. With it, he raised the field of cosmology from niche subject to a subfield to be reckoned with. Hawking was a rule breaker, a creative thinker, and someone who had thought deeply of both his own mortality and that of the universe’s—and the world loved it. A Brief History of Time dominated the London Sunday Times bestseller list for five years, defying all expectations and marking Hawking as the preeminent scientific thinker of our time.

In more recent years, Hawking was outspoken about his thoughts on technology’s role in our lives. He incited controversy by calling for the academic boycott of Israel. He tackled wormholes and time travel, and warned humans of trusting artificial intelligence too freely, suggesting that we should remain independent and wary of creating increasingly effective computers.

Ultimately, Hawking’s biggest contribution to science was to make it less dull and foreign and to point to the fact that the cosmos held the secrets to who we were, who we are, and what we will become. That required not just publishing multiple books and delivering sold-out speeches but also making his biting, irrepressible presence known in pop culture moments.

And while Hawking became known for his wheelchair and touchscreen, which allowed him to communicate in the last decades of his life by moving a single muscle in his cheek, he never allowed ALS define him. His appearances, cartoon or otherwise, always ensured that he was in control of his narrative; while he couldn’t speak or move independently from ALS, he could make his presence known. Despite the fact that he could not live independently, his mental faculties were intact and better than most anyone else’s. And even though he could not physically speak or write, he could communicate eloquently.

In one of his first forays into pop culture, Hawking played poker on Star Trek with the physicists whose names will be uttered in the same breath as Hawking: Isaac Newton, the man who mythically figured out gravity when an apple toppled on his head, and Albert Einstein, whose theory of relativity established spacetime and accurately predicted the existence of gravitational waves. Lieutenant Commander Data leads the nerd sesh, but even among the spectacular guests present, Hawkings delivers a memorable one-liner directed at Newton’s braggadocio about “inventing physics”: “Not the apple story again,” Hawking sighs. Hawking ends up winning the game, making a sly statement about the fact that despite his disability, he can not only beat the greatest physicists of our time with a poker face, but grin spectacularly and triumph.

In his appearance on The Simpsons, Hawking transcended his illness in a world where he is able to produce a boxer’s glove to punch down his naysayers, and pop out helicopter blades to fly away and hover, physically and intellectually, over others.

Then there was his appearance on the sitcom The Big Bang Theory, where he puts the normally obnoxious nerd Sheldon in his place by pointing out a simple arithmetic error. Finding it, he wryly states, “was quite the boner.”

Hawking could have retired from the public eye after his devastating diagnosis, but that he integrated himself into pop culture to become the face of physics—science, really—is a noteworthy achievement. In this day and age of social media and instantaneous communication, Hawking was a reminder that technology could be harnessed to bring out the best of us, so long as we were aware of its limitations.

In a way, Hawking’s ability to break the barriers of his physical incapacity shows the indescribable power of the human spirit. Physics can explain how we move through our physical spaces, but sheer determination and genius can be more mysterious and astonishing than the physics of the Big Bang. For Hawking, perhaps the greatest physicist of our time, physics was something he redefined and conquered.