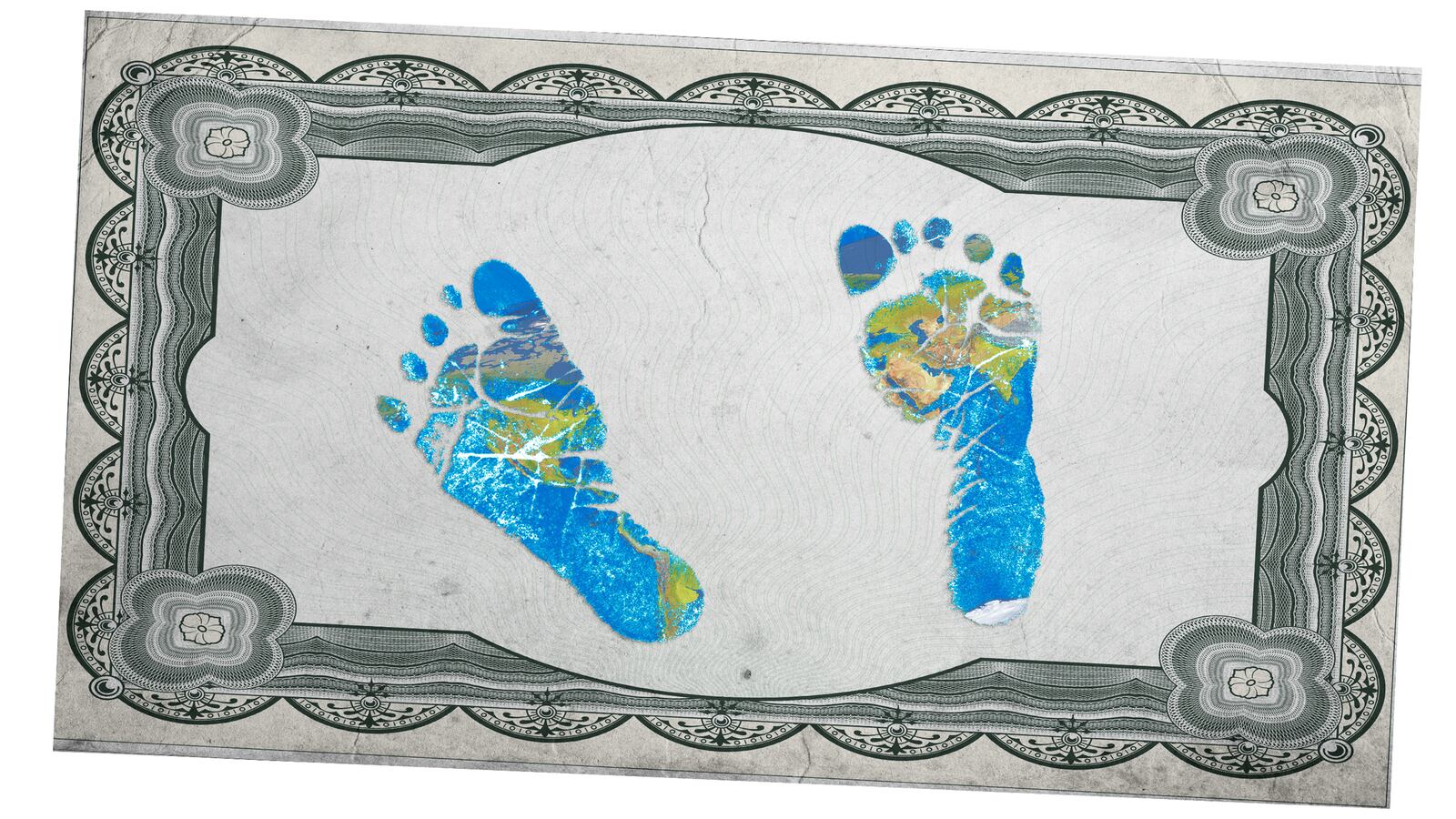

Dire climate reports are piling up, making one thing increasingly clear: We’re about to lose a lot to climate change. One million plant and animal species will be at risk of extinction. Rising sea levels will drown coastal cities. Even our beer won’t be safe. And some economists think humans will see a drop in fertility, too.

But a new study, published May 3 in the journal Environmental Research Letters, says that might not be true.

Instead, fertility—defined in an economic context as the number of children families choose to have—could actually increase near the equator, the researchers suggest.

And that’s not a good thing. Rising fertility rates will likely lower the educational investment that each child receives, the researchers add, further exacerbating the economic inequality that climate change will bring.

The multinational team of researchers developed a model that simulated the economies of two countries—Colombia and Switzerland—that spanned five 20-year generations of hypothetical parents. Those parents had to navigate what co-author Gregory Casey describes as the “quantity-quality trade-off”: the choice of having more kids, or investing more resources in the kids they already have.

“In any decision in life, we know that all people have finite time and finite money to spend on various things,” Casey, an assistant professor of economics at Williams College, told The Daily Beast. “Another thing we know for sure is that having children takes both time and money, and investing in a child’s well-being takes both time and money.

“So if all those things are true, it must be that we face some kind of trade-off between investing in the well-being of each child, versus having more children.”

Climate change, the researchers postulated, would impact nations heterogeneously by skewing the cost-benefit analysis of having an additional child. In countries close to the equator, like Colombia, researchers said, rising temperatures will make the nation too warm to sustain agricultural production at previous rates, causing the agricultural yield to drop.

That, in turn, will cause the demand for crops to rise, and lead to wage increases for agricultural workers. Because agricultural work doesn’t require much traditional education, the authors believe, families will use fewer resources educating their existing kids, and more resources having new ones.

The opposite will be true in more northern countries, the researchers suggest, where rising temperatures will bring nations closer to the ideal growing temperature for most crops. In countries with colder starting climates, supply will rise and agricultural wages will drop, which will incentivize parents to invest more to educate fewer children.

That theory was borne out in the model.

First, the researchers ran a simulation of Colombia’s economy under RCP 8.5—a drastic climate projection that suggests that global temperatures will rise 10 percent in Colombia by 2100—and found that Colombia’s child population will be 1.35 percent higher than the baseline simulation by the end of the century.

But when the researchers simulated Colombia’s economy at a higher latitude (the latitude of Switzerland), fertility dropped by 3 percent.

Next, the researchers tried running the model with Switzerland, a richer country, to see if a nation’s level of development impacted the results.

It didn’t. The team found that the development status of a country made “essentially no difference” in predicting fertility rate.

These findings are bad news for countries near the equator, because higher fertility and lower investment in each child’s education has been repeatedly linked to lower incomes for those children. (It’s also unfair: the northern countries that stand to benefit from this mechanism, Casey noted, are also the ones which are primarily responsible for putting too much carbon in the atmosphere in the first place.)

There is hope. When researchers ran the Colombia model with the much more conservative RCP 2.6, which assumes global collaboration to fight climate change and projects only a 3.3 percent temperature increase, the uptick in fertility wasn’t noticeable.

“In other words, strict mitigation policies can essentially eliminate the demographic consequences of climate change at low latitudes,” the authors write, “at least when restricting attention to the quantity-quality mechanism our model investigates.”

The authors emphasize that their study isn’t meant to be a definitive statement on the fertility rates of the future—and that health, trade, and migration data, which are not included in the model, would play a role in determining fertility, too.

“Of course, we know […] it’s very generalizing for childhood and adulthood. These are very limiting factors, and of course, in the real world, things are more complicated,” Soheil Shayegh, a co-author of the paper and a researcher at the European Institute on Economics and the Environment, told The Daily Beast.

Some researchers who aren’t affiliated with the study believe that the limitations are too significant to trust the paper’s conclusions—including David Lindstrom, a sociology professor at Brown University, who said he was “skeptical” of the results.

“While a decline in agricultural productivity due to climate change might drive up local food prices, it will also drive many small landholders off their farms due to the declining marginal productivity of their land, creating a surplus supply of rural workers,” Lindstrom told The Daily Beast via email. “It is cheaper for a farmer who stays on his land to hire a worker than to have more kids.”

“These types of models often have to treat countries as closed systems, but we know that national borders and economies are much more open […]” Lindstrom added. “In open systems it is much harder to anticipate how people will respond to climate change.”

Casey acknowledged that there’s “a lot” of limitations in the study—but he believes it still has value. “There seems to be this gap between what economists focus on for long-run outcomes and what’s happening in these climate change models,” he said. “So we think of ourselves as kind of a first step in trying to bridge this gap.”

Brian Thiede, a sociology professor at Penn State University who was also not affiliated with the study, echoed some of Lindstrom’s concerns—and added that only some women have access to the contraceptives that would allow them to truly make choices about their fertility.

But he nevertheless agreed with Casey and Shayegh’s belief that the study provides valuable insight into yet another way that climate change could impact our future.

“This paper draws much-needed attention to the potential links between climate change and human fertility,” Thiede told The Daily Beast via email. “This topic has been under-studied by demographers, but is important because the number of children born to a woman can affect households’ welfare and ability to adapt to future climate shocks.”