In March 2011, a massive earthquake struck the coast of Japan and triggered a tsunami that resulted in the Fukushima nuclear disaster. In April of that year, hundreds of tornadoes tore through the southern United States.

The signs were looking up for veteran Doomsday forecaster Harold Camping’s third end-of-days prediction. This time the Christian broadcaster had the May 21, 2011, date right, he proclaimed, and everyone should prepare for the arrival of Judgment Day.

While Camping’s predictions received some airtime and provided a brief respite from the natural disaster talk, not many rushed to get ready. His own employees were skeptical. A receptionist for his organization, Family Radio, told CNN that she thought around 80 percent of her colleagues didn’t believe the end was nigh.

Camping was part of a long tradition of apocalyptic preachers that began before there was even a Christ to return for the righteous. While Romulus may have believed in a 7th-century B.C. sign foretelling the end of the Roman civilization, the roots of U.S. belief in an imminent Judgment Day are a little more recent: they were firmly planted by one mid-19th century preacher.

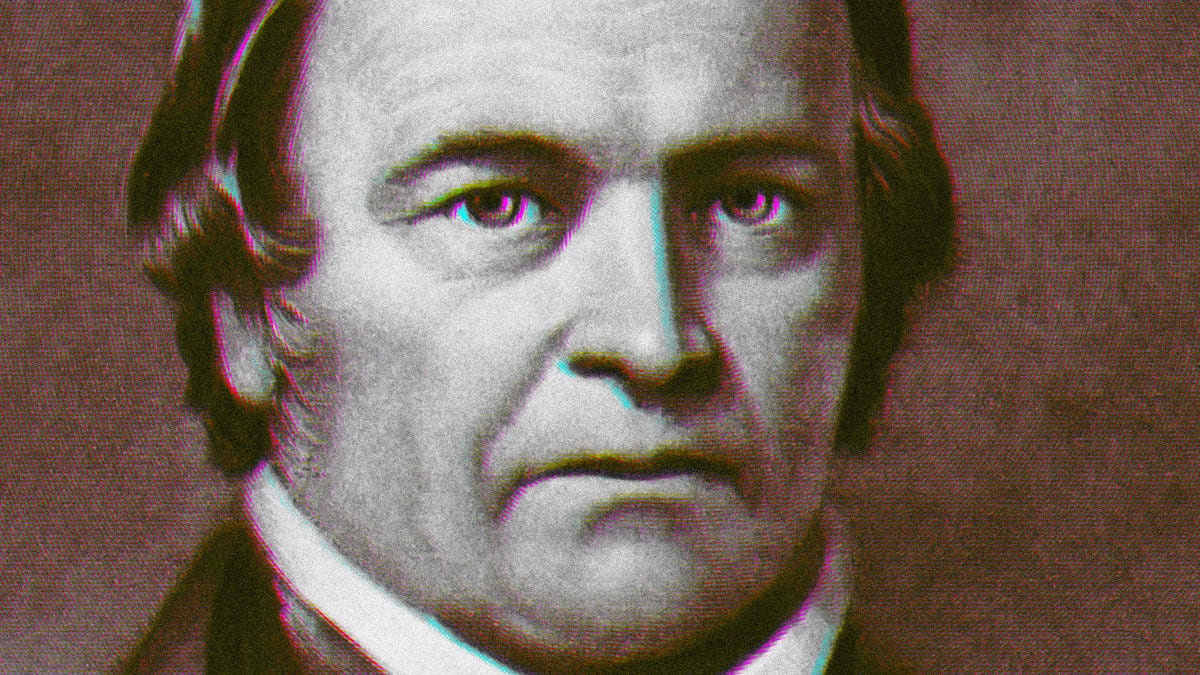

William Miller was a devout Christian and a devoted scholar of the Bible who announced in 1831 that he had decoded the date of the Second Coming. It would happen sometime within the year following March 12, 1843, he preached at every tent revival he could.

His reasoning was methodically produced, he gave plenty of advance warning, and he had an acolyte who was great at publicity. In short, Miller had everything he needed to accrue believers and headlines. While the press was skeptical of his claims and covered them as such, it is conservatively estimated that 50,000 people prepared to be spirited away, though those estimates reach as high as 100,000. They gave away businesses, settled their affairs, and some donned white robes. Needless to say, the episode touted to be the event of humanity’s lifetime turned out to be known as the Great Disappointment.

Americans may not have confronted the modern horrors of nuclear disaster in the first half of the 19th century, but things were tough enough. The War of 1812 had recently ended and westward expansion was in full swing. Life was uncertain and severe for many (though it should go without saying it was even worse for the Native Americans whose lands were being stolen and whose people were displaced and murdered). Because of this, it is no surprise that religion flourished in the historical period that would become known as the Second Great Awakening.

According to a PBS interview with Professor L. Michael White, the increasingly popular revivalist movement was centered in New York, which became known as the “burned over district,” and many of the new religious sects sprouting in this area had “apocalyptic overtones.”

Miller fit the profile. He hailed from the Empire State and was a largely self-taught man who took to farming and religion after serving in the War of 1812. He attended Baptist services, but also began an intense study of the Bible on his own.

It was during this time of reflection and deep reading, followed by frantic scribbling of numbers and calculations, that he came to a profound revelation: the Second Coming would occur in his lifetime.

In a 1996 article in Reviews of American History, Benjamin McArthur characterizes Miller as a “reluctant prophet.” He came up with his D-Day calculation in 1816, but he waited a full decade and a half before he began to share it with others. (Another way of looking at this is that he gave himself a 15-year head start on his righteous preparations.)

But by 1831, Miller was starting to make the tent revival rounds. By all accounts, he was the opposite of the fire-and-brimstone doomsday preachers of our modern imagination. Miller was a true believer, but he didn’t quite have the panache from the pulpit that makes for a truly effective prophet. According to White, his sermons were best characterized as “lectures.”

What perhaps saved his efforts to save humanity was meeting one Joshua V. Hines of Boston in 1839. Hines made up for the PR acumen that Miller lacked. Under his direction, pamphlets and posters were printed up and widely distributed. Miller also began to branch out from the rural revival scene to spread his message to the cities where, let’s be honest, citizens were probably in greater need of saving.

But with this growth also came a loss of control of the message, particularly as 1833 dawned. The only thing worse than waiting for a day that you’ve eagerly anticipated and that has long been promised as a reward for your angelic behavior is having been given no exact date. But waiting through uncertainty is what Miller’s vague prediction required of his followers.

Throughout the year, newspapers reported on the group that became known as the Millerites. This coverage ranged from downright nasty to gently dismissive. Some mocked believers who were spotted doing things like making home improvements or buying livestock. Others chastised the hubris of one religious sect believing they had a better interpretation of the Bible than the many other righteous faithful in the country.

While the press as a whole may not have bought into Miller’s claims, papers around the country were more than happy to use the doings of the believers as entertainment.

One Cleveland, Ohio tailor, “named Eal, an out and out Millerite, was recently missed for several days from his residence. On searching the neighborhood, he was found in a piece of woods adjoining the town, seated upon a log with a bible in his hand, patiently awaiting the coming of the Second Advent!” reported The Times-Picayune on April 25, 1843 in an article titled “A Mad Millerite.”

In early February of 1846, the Lincoln Journal noted that, “The women were pale and ghostly from watching and praying, and in fact, the whole population, or at least those who believed in the coming ascension, looked as if they were about half over an attack of the chills and fever.”

In May of 1846, one newspaper told the story of a man who attended a Millerite revival in Belchertown, Massachusetts, who was so overcome with talk of the imminent day of reckoning that he stuck his hand in the fire and subsequently died from his burn wounds.

The year came and went, but that did nothing to deter the Millerites from their beliefs. Some quick recalculations were done by Miller’s followers, and a new day was settled on: Oct. 22, 1844.

With the eyes of the entire group now on one specific day, preparations went into full swing. Newspapers reported on cobblers and farmers who sold their tools and businesses; on families who got rid of all their earthly possessions; on the crowds of men, women, and children who gathered at the Boston Tabernacle raising their voices in prayer as they awaited Christ’s return. “Some of their exhortations—though honest—partake a little of the ludicrous, and provoke a smile from ‘both saint and sinner,’” the Washington Telegraph reported.

There were also plenty of bystanders who gathered, ready to watch the true believers be spirited away or confronted with their false beliefs.

Oct. 22, 1844 came and went in the manner of any other ordinary day. “Although we gazed long and anxiously at the roof, we saw no indication of its rising and concluded that the country was perfectly safe for a little while longer,” one Boston reporter standing outside the Tabernacle wrote.

The day became known as the Great Disappointment, and it was the end of the Millerites for all intents and purposes. As thousands of Millerites were left to pick up the scattered pieces of their lives, the religious sect disbanded. Some joined even more extreme religious groups, others went on to found the Seventh Day Adventist Church. By the very next decade, the Millerites were nothing more than a historical note.

But it is a note that is still firmly planted in American memory. If history can tell us anything, it’s that the Great Disappointment did not stop the endless tide of apocalyptic prophecies.