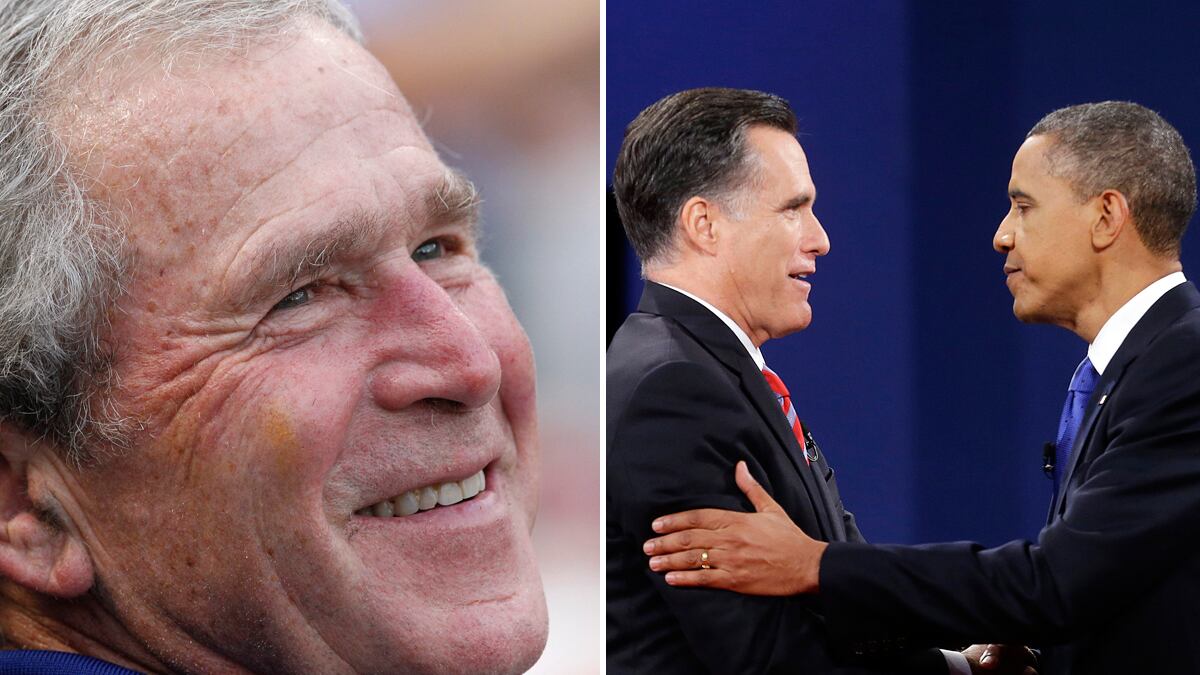

Barack Obama didn’t win tonight’s foreign-policy debate. Neither did Mitt Romney. George W. Bush did.

Bush won it because the framework for understanding the world that he put in place after Sept. 11 still holds, even though it wildly distorts the world that the next president will actually face.

The Bush administration essentially defined American foreign policy as American military policy. The Bushies dismissed the Clinton administration’s emphasis on international economics as what Charles Krauthammer dubbed a “holiday from history.” In the Clinton era, treasury secretaries had been powerful foreign-policy players. In the Bush administration, they became foreign-policy afterthoughts. And judging from tonight’s debate, international economics remains an afterthought.

Yes, there was some discussion of outsourcing and some bashing of China for not playing fair on trade. But there was virtually no discussion about the vast shifts in economic power that are remaking the globe. To listen to the candidates, you’d never know that the Chinese are now the largest source of aid and investment in much of the poor world. You’d never know that the European Union faces collapse. You’d never know that a couple of years ago the world financial system almost broke down, and could again.

Obama, Romney, and Bob Schieffer discussed foreign policy almost exclusively through the Bush prism. The focus was on countries where the United States is already at war, or soon could be.

To be sure, Obama and Romney don’t want to approach those countries in the same way that Bush did in his first term. We no longer have the money or will to launch ground wars. Today, the preferred options are military training and aid (Afghanistan, Syria), drone strikes (Pakistan, Yemen), and perhaps a full-fledged air war (Iran). But the “war on terror” still largely defined which countries received attention. And as a result, the candidates spent an inordinate amount of time talking about weak, dysfunctional countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Syria and barely any time talking about fast-growing, increasingly powerful ones like India, Turkey, and Brazil. The only country in sub-Saharan Africa to receive a mention was one of its weakest and most remote, Mali, because they have some al Qaeda there.

George W. Bush’s core mistake was his belief that because al Qaeda had bloodied us, it was the 21st-century version of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. It never was, because in the mid-20th century, what made Moscow and Berlin genuine competitors was their economic strength. The true successor to those once-fearsome powers is not the mud-hut totalitarianism of al Qaeda, but China, and perhaps India and Brazil, countries that are becoming economic models for billions in the poor world.

How the United States, its own might sapped by the financial crisis and wars of imperial overstretch, meets the challenge posed by countries that are converting their economic success into geopolitical power is the defining foreign-policy question of our time. Not only wasn’t that question answered tonight, it wasn’t even posed.