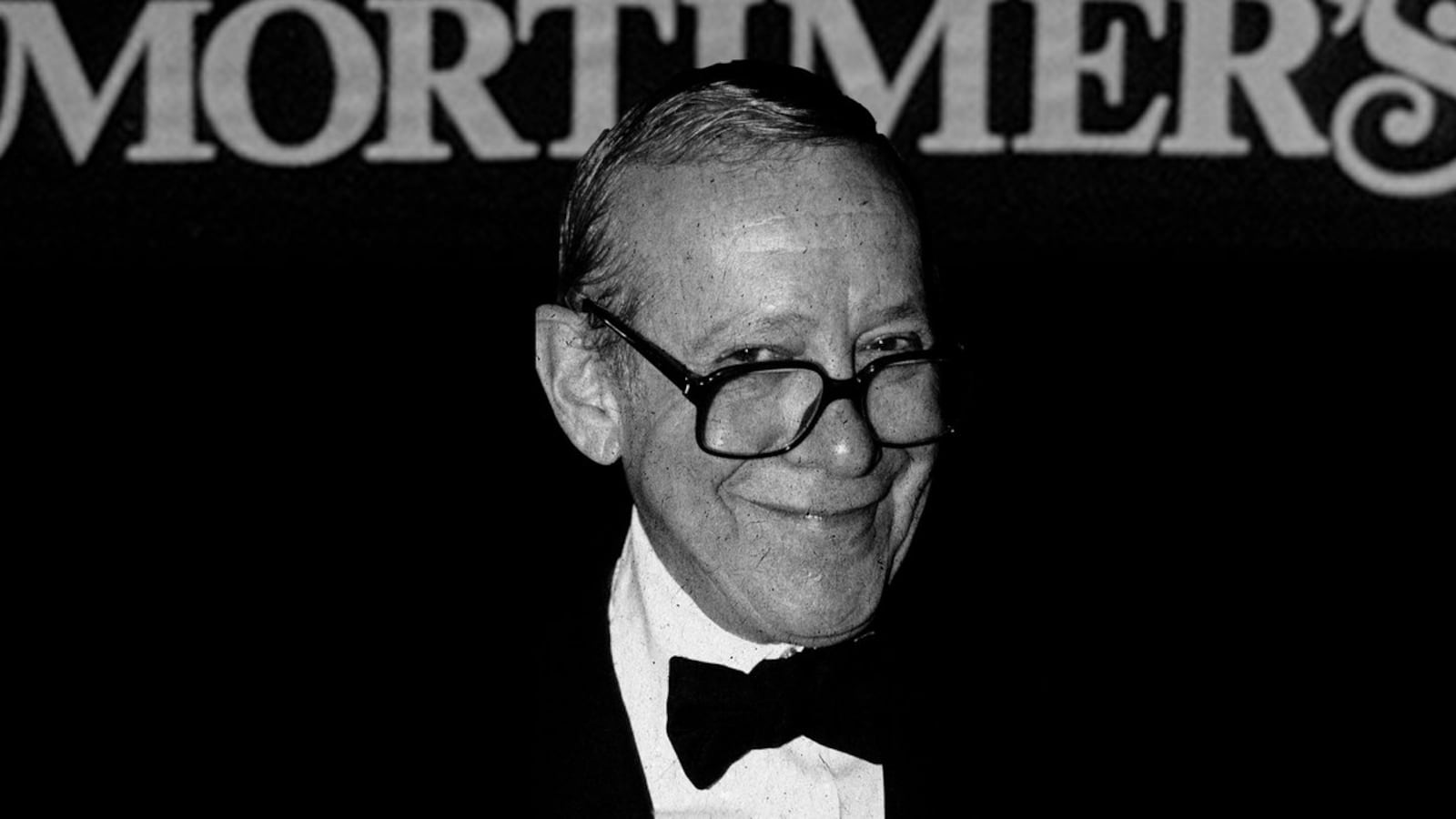

“I’ll never leave this place,” Glenn Bernbaum, owner of the exclusive New York City restaurant Mortimer’s, repeatedly told me as his friend and attorney.

In the small hours of Sept. 8, 1998, Glenn died with his boots on, peering into his murky bathroom mirror, suddenly stricken by liver failure. He keeled over backwards, smashing his head against the tiled wall. During all his shaves and showers, he never thought a bath mat would be his last stand, and Glenn did “not go gentle into that good night.”

He landed on his back in the tub—and in that instant Claus Von Bülow, Henry Kissinger, Dominick Dunne, Bill Blass, Kenny Lane, Nan Kempner, Elizabeth Taylor, Jackie O and glossy luminaries of all shapes and sizes were no longer going to toss their salads over Palm Beach gossip and Locust Valley plans at lunch.

For more than 20 years, Mortimer’s had been a magnet for everybody who was anybody. (A new book, Mortimer’s: A Moment in Time, by Robin Leacock, Robert Caravaggi and Mary Hilliard, has just been published, recalling the vertiginous heights of social climbing by the likes of Carolina and Reinaldo Herrera, C.Z. Guest, and Brooke Astor.)

Now Mortimer’s would be closed, shuttered forever.

My only specific instruction, as recited in Glenn’s last will and testament, which I painstakingly drafted, was: The minute I die, close Mortimer’s, padlock the front door.

Celebrities and socialites were regulars for dinner and parties at Mortimer’s. From left to right: Fashion editor Elizabeth Saltzman and actor William Baldwin, Iman, Calvin Klein and Nan Kempner, and Ivana and Donald Trump.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyAt 7 a.m. that day I was called by Mortimer’s charming, battle-scarred maitre’d, Robert C. informing me of Glenn’s death. Robert, not through eavesdropping, directly knew I had discussed the end many times with Glenn at Mortimer’s during our late afternoon meetings dating back to the ’80s.

Glenn would call after lunch: “Mr. Golub, if you have nothing better to do, come over and let’s talk about my estate, I need a new will.” (Later in life I learned that nearly everyone needs a new will because so many heirs prove to be undeserving.) Whatever I had on my plate that day was not going to be as much fun as talking to Glenn about his testament plus anything else under the sun including his favorite subject—his net worth.

There were more stories in his repertoire than socialites in his address book and many of their travails were part of our consultations. Needless to say, everybody who was anybody ate or wanted to eat at Mortimer’s. In one will that endured for 10 years—several others followed—he bequeathed all of his worldly possessions to the animals in the Bronx Zoo. I urged him to be specific but he refused to name any of them personally.

In a will supposedly drafted in the late ’70s by Roy Cohn, no longer Esquire at that point, Glenn named maître d’ Stefanos Zachariadis as his sole heir. However, after Stefanos was convicted of plotting to murder Glenn in order to expedite his inheritance, there was more than ample reason to draft a new document.

On the day of Glenn’s death, after I arrived at Mortimer’s to fulfill his instructions (stopping on the way at Lexington Hardware to purchase a large padlock and six feet of chain) I was escorted to his private rooms above the restaurant by the police. A burly 19th Precinct cop stood guard inside the apartment in front of the bathroom and presumptively briefed me. “There is no evidence of foul play.” The faux audition for Law and Order continued: “The body is behind that door, Mr. Bernbaum is dead.”

I would have to take his word for it. No civilian would be permitted to see the corpse although when it comes to drafting wills and the eventual follow up, I usually like to observe the cadaver or the mortua persona. Professional courtesy, no charge.

Bill Paley, Rosie Hall, Cindy Hall, Jerry Hall and Ahmet Ertegun at Mortimer’s back in the day.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyGlenn and I didn’t have much in common but we were good friends, probably because I grew up in a tenement right above my father’s grocery store. The food business is a tie that binds. Every time I passed Orsay in the past few years, known for its fine French cuisine, Frenchified bistro décor and for taking over Mortimer’s space, I sensed a nudge towards the front door. Think Pacino in Godfather III: “Just when I thought I was out they pull me back in.”

As time went by, the corner of Lexington and East 75th Street was getting more difficult to avoid. Early this April I relented and decided to have lunch at Orsay without a reservation.

Upon my arrival, Olivier, the gray-suited maître d’ unhesitatingly guided me to the left. It was the room where I always met with Glenn, and Olivier’s outstretched hand indicated the precise banquette and table. Naturally I sat there.

After the usual acclimation, I ordered the grilled Scottish salmon filet, a frisée salad, and a glass of iced tea. I’m on a strict diet but I oddly hesitated and considered the chicken hash or the famous Mortimer’s twin burgers, because I heard Glenn’s unmistakable gravelly voice confirming, “They are to this day the best things on the menu.” I whispered “Stop it Glenn, the kitchen is closed.”

The waitress, an attractive brunette named Devon in her twenties, brought me the iced tea. It was then I felt compelled to tell her who I was, along with an irrepressible need to talk about Mortimer’s and Glenn. I wasted no time informing her how he’d passed away and that I closed the place. I included the fact that Glenn died upstairs. Then unconsciously I muttered, “If these walls could talk…”

Devon didn’t hesitate.

“You mean the old man upstairs? I have seen him walking around with his cane, his hand is always trembling. I know he is the owner—I mean, was the owner a long time ago. I recognize him.”

I asked, “Did you know the upstairs, now the events room, was Glenn’s apartment?”

She simply said “Yes,” and walked away.

After that revelation, I idiotically looked around for the old man, telling myself to eat and leave while I nervously picked away at the salmon. My appetite was gone.

Minutes later, Devon returned accompanied by another waitress who couldn’t wait to tell me something. “I have seen the old man many times upstairs, it is scary to go up there because he is walking around, there is a lot of activity up there. Even the exterminator talks about seeing him, he’s here in the morning and you can come and speak to him.”

Workers at Orsay swear the upper floor is haunted by the Mortimer’s proprietor, who met his end there.

Aaron Richard GolubA few days later in furtherance of my research into the occult, I enjoyed another lunch at Orsay. This time I spoke to Claudio, the Wednesday maître d’ who in a businesslike fashion informed me, “I have seen the old man, he’s always wearing a dark suit, upstairs he’s walking around, I can hear him. His image appears on the restaurant’s security cameras. Even the exterminator (still nameless) has seen him early in the morning. He goes into the party room and disappears. The whiskey bottles, wine glasses on the bar late at night sometimes make noise, they touch each other, clinking. I don’t pay attention, because if I do, the rattling becomes more intense.”

If that didn’t top Tales from the Crypt, my waiter, Ryan, who looked like a part-time GQ model, added out of earshot of Claudio, “There was a Bengali busboy here who said during the early pandemic that he saw the old man and heard the serenading bar bottles and glasses. I’m planning to bring a Ouija board to work very soon and let’s see.”

Now I’m determined to find the old man in the suit. This isn’t my first rodeo. When it comes to eerie and weird, Psycho actor Tony Perkins was my brother-in-law. Norman Bates would insist that I go upstairs at Orsay and bring mother and Glenn their dinner.

Aaron Richard Golub is a prominent New York City trial lawyer who has worked on high-profile cases involving Tom Brady, Donald Trump, Martin Scorsese, Brooke Shields, and Gisele Bundchen. He has been featured on the cover of New York magazine and in GQ’s “12 Guys You Should Know.” He is the author of The Big Cut and recently finished a new book, Ruckus.