Forty years ago I was a new college graduate and teaching at a summer school where one of the novels on the syllabus assigned to me was by the Mississippi-born Nobel Laureate William Faulkner. I didn’t like it, not the first time anyway. So I reread it, hoping to find something I could tell my students, and then reread it again—and after that I seemed to fall down a great well. All I knew was that I had to have more Faulkner, and at once, had to read him all summer long, from the ghoulish “A Rose for Emily” to the Jazz Age despair of Sanctuary and on to the hall-of-mirrors called Absalom, Absalom!

I had been a high school wrestler and Faulkner’s sentences often left me feeling as wrung out as I had ever been on the mat. I liked the intellectual workout, the dense language, the experimentation with fictional form—and yet over the years I came back for other things too. For what he gave me above all was the sense of a past that, as he famously said, is never past.

Faulkner was a white man of the Jim Crow South, and his greatest novels are haunted by the legacy of slavery, by the strangling force of a history from which his world can never fully escape. The consciousness of race gnaws at the very soul of his people, and his work provides the richest account of our national reckoning that any white writer has yet produced.

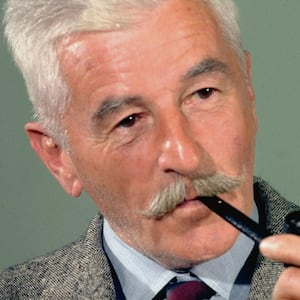

I have been reading and teaching Faulkner’s work ever since that summer, and more recently writing about it too. Last month I published a new book, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, a book that asks a few simple and complicated questions: What can the war tell us about him, and what can he tell us about the war? How can we use the central crisis in our national history and our greatest 20th century novelist to think about each other?

I won’t try to answer that here, but I do want to explore a question that readers often ask me. Some of Faulkner’s books offer the most disturbing of family tragedies. Others will make you laugh aloud, and his pages contain the richest and most varied gallery of characters in all of American literature. There is, however, one problem. He wrote 19 novels and over 1,000 pages of short stories, many of them drawing on the same characters and set in the same imaginary Mississippi county. So just which one should you start with?

Much of the Yoknapatawpha cycle seems to have lived in Faulkner’s head before he finished any part of it, but he didn’t write in sequence and liked to throw his readers into the middle of things. That’s famously true of The Sound and the Fury, which opens in 1928 before diving back to 1910 and even earlier, and yet it’s also true of his densely interwoven oeuvre as a whole. He will begin a plotline in one book and finish it in another, and sometimes a novel’s action seems predicated on that of a story he hadn’t yet written. It’s hard to know where to begin with Faulkner, and yet one thing is certain. You shouldn’t start with the first book he wrote about his imaginary county, the place he defined as his “own little postage stamp of native soil.”

He called that novel Flags in the Dust, and it offered a picture of a small Mississippi town named Jefferson at the moment when the soldiers and fliers of the Great War have begun to come home. Yet Jefferson is haunted by another war as well, and a statue of a Confederate soldier stands in front of its county courthouse. Flags in the Dust is about the Lost Generation and the Lost Cause too, and also about the relations between Black and white, town and country, in a world that is at once rapidly changing and static. Loose and baggy and brilliant, the book relied on a communal history that existed only in Faulkner’s own head. Not on the page, not yet; it was no wonder that the avant-garde editor Horace Liveright rejected it as “diffuse and non-integral.”

Eleven other publishers agreed with him before a firm called Cape and Smith took it on, though only if Faulkner could first slice it by 40,000 words. But he couldn’t—the cutting was simply too painful. A friend named Ben Wasson took the job on instead and told Faulkner what the problem was: “You had about six books in here.” In it he had invented the world he called Yoknapatawpha County and written down everything he’d imagined in a way that no reader could entirely follow. Wasson’s version was more coherent, and appeared early in 1929 under a new title, Sartoris, the family name of its main characters. The original text of Flags in the Dust saw print only in 1973, a decade after Faulkner’s death, and that’s the book one buys today. For the novel makes perfect sense now—provided you’ve read a lot of other Faulkner first.

So where should a reader begin with America’s greatest 20th century novelist? Here’s what I tell the people who ask me.

ONE: As I Lay Dying, first published 90 years ago this October. Not that it’s easy; no Faulkner is easy. He splits the book between 15 different first-person narrators, and some chapters dive deeply into their speaker’s fractured consciousness. Other narrators speak colloquially, though, as if telling a story to their neighbors, and the novel doesn’t depend in any significant way on the backstories provided by Faulkner’s other work. We follow the mule-drawn wagon of the Bundren family as they try, in the July heat, to move the corpse of the clan’s matriarch some 40 miles to its burial place, watching—and smelling--as they are delayed by a series of disasters. It stands as a modernist triumph, and anyone who finishes it will have a sense of achievement. Nevertheless it remains accessible, and often appears in high school classrooms. I don’t usually agree with curricular choices that schools make. No adolescent should have to read The Scarlet Letter, but in Faulkner’s case the syllabus is right.

TWO: Light in August (1932) is also self-contained and provides a total picture of Jefferson’s social and physical geography, with its boarding houses and decaying mansions, its jail and its courthouse square, its Black neighborhoods and white ones too. The novel’s three separate plots are as intricately dovetailed as anything in Dickens, but Faulkner fills it with a series of unVictorian skips in time, and we’re a hundred pages in before we realize who its main character will be. That’s the hard-faced bootlegger Joe Christmas, a man who may—or may not—have some Black ancestry. For this novel is also Faulkner’s first attempt at his greatest theme, the rigid uncertainties of the color line in the Jim Crow South.

THREE: The Sound and the Fury (1929). The book that made Faulkner’s reputation. He began it after getting his first rejection for Flags in the Dust, and believed it would remain unpublished. It doesn’t depend on the as-yet unwritten history of Faulkner’s apocryphal county, but its style makes extraordinary demands on its readers: a book about the operations of consciousness that requires the same level of attention as James Joyce’s Ulysses. It opens in 1928 in the mind of the 33-year old Benjy Compson, a mentally disabled man who cannot distinguish between past and present. That lets Faulkner play hopscotch with his readers, bouncing us in Benjy’s mind back to the turn of the century and then returning to the “present,” before dropping back again, and again, and forward once more. After that the book moves up to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and into the mind of Benjy’s suicidal brother Quentin on a June day in 1910. It’s exhilarating, but it is a book you need to train for, as though for a mountain hike. Anyone who’s read As I Lay Dying and Light in August should be ready.

FOUR: Absalom, Absalom! (1936) uses the Compson family to explore the burdens of Southern history. Quentin’s Harvard classmates all want him to “tell about the South," and the story with which he explains the region goes back a century, to the early days of the slave society in which his ancestors made their fortune. It is Faulkner’s greatest book and for me the most important novel any white American has written about our country’s racial history. It’s also about the very process of historical understanding, the way we grope toward a knowledge of a past in which “happen is never once” and nothing is ever really finished.

FIVE: The Unvanquished (1938). Writing Absalom, Absalom! proved such a strain that Faulkner sought relief in a series of half-comic stories about the Civil War. Nobody would claim that they are among Faulkner’s best work, but these seven tales provide an essential account of Yoknapatawpha’s early history. They are the backstory on which so much of Faulkner’s other work depends, and their narrator is the young Bayard Sartoris, who as an old man had stood at the center of Flags in the Dust.

After that the country lies open, and there are a dozen more books in the Yoknapatawpha cycle to choose from. You could now pick up Flags in the Dust, or maybe the grim noirish Sanctuary, which Faulkner’s publisher thought might land them both in jail for obscenity. I often return to Go Down, Moses, in which Faulkner follows the Black and white descendants of a single Mississippi planter over four generations. There are great short stories, like “A Rose for Emily,” an archetype of Southern Gothic, or “That Evening Sun,” in which Faulkner draws upon the blues, and then there’s the saga of the Snopes family, beginning with The Hamlet, poor whites who rise from sharecropping to social prominence.

Knowing where to begin with Faulkner may be difficult. Knowing where to stop is harder. Not that you have to, and I envy anyone who picks up these books for the first time.

Michael Gorra’s The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War will was published in August. He is the editor of the Norton Critical Editions of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury and author of Portrait of a Novel: Henry James and the Making of an American Masterpiece, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Biography. He teaches at Smith College.