Scan a menu in a craft cocktail bar and it’s a lead-pipe cinch you’ll find something on it made with rye—straight rye whiskey, that is, made right here in the United States. For drinkers under, say, 35, it’s even a given. But those of us older than that can recall the days when if you asked for a rye Manhattan they would give you something made with Canadian “rye,” which oddly enough can be made with no rye in it at all. Indeed, things got so bad that the whole category almost completely disappeared. The troubles really began at the turn of the century with World War I and Prohibition on the horizon and then they only got worse.

The story of Old Overholt, which I began in my last column, is really the story of the whole Mid-Atlantic rye whiskey industry, and of industrial America. The rise, the fall and the rebirth—it’s a history that to my knowledge has never been fully explored and needs to be for this style of whiskey to be more than a fad. Here is the full unabridged story of how rye whiskey, our first indigenous distilled spirit (it goes back to 1648) almost became a footnote in American history.

In 1910, when Overholt rye whiskey celebrated its 100th anniversary, things were going very well for the company. After beginning in a small log still-house in 1810, the Overholt whiskey enterprise had grown and grown until it was one of the largest and most respected whiskey-makers in the country.

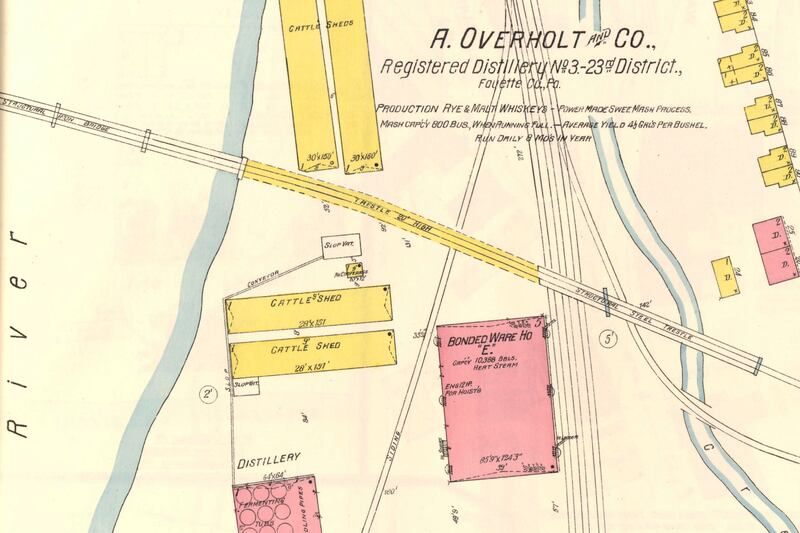

It was still owned, at least in part, by its founder’s grandson, Henry Clay Frick, one of the richest and smartest businessmen in the country. Its distillery at Broad Ford, Pennsylvania, 30 miles south of Pittsburgh, although not the largest or most modern in the industry, was still plenty large and modern, with a new bottling line and a new cooperage. (It was making its own barrels for the first time in years as a measure to improve quality.) Its stocks of aging whiskey were vast. Its reputation for quality was strong and long-established.

From its headquarters in Pittsburgh’s modern Frick building it administered a network of sales offices around the country. There were few distillers, if any, better equipped to survive the high winds and breaking waves of the 20th century, a century that, it turned out, didn’t like rye whiskey and it really didn’t like local traditions, local ownership or local markets.

As if to announce that animus, the new century inflicted a near-death experience on Old Overholt practically right out of the gate. On the afternoon of Nov. 19, 1905, a young bottling-line worker noticed flames coming out of an upper story of Warehouse D at the Broad Ford distillery. Within minutes, the whole warehouse, which held 16,000 barrels of rye, was on fire, sending whiskey-fueled flames shooting high into the sky. By dint of and heroic effort from the distillery workers and the local fire departments and quick thinking from the plant engineer, who knocked the valves off the heating pipes in the other warehouses to fill them with fire-suppressing steam, the fire was contained to that one warehouse and the 810,000 gallons of whiskey it contained—some three months worth of production.

But Overholt could always build more warehouses and make more whiskey. What it couldn’t do is make more voters.

As Prohibition crept over the land—by 1913, nine states were completely dry and another 31 were dry by local option—things began to get grim for the American alcohol industry and distillers in particular, with brewers and winemakers trying to throw them over the side in an effort to keep beer and wine legal. In some markets, Overholt’s advertisements switched from cornily-illustrated appeals to taste and tradition to assertions of the brand’s medicinal value. Some of these ads, showing a canny understanding of the prohibition movement, even appealed to women by positioning Overholt as a traditional item in the family’s medicine cabinet, there to be drawn on by the lady of the house as part of her role as the guarantor of the family’s health. “Grandmother knows well the value of a hot toddy for a cold—an unfailing remedy since her girlhood days,” says one, while another, under a picture of a stylishly-dressed young matron opening a medicine cabinet, proclaims Overholt “the premiere whiskey for medicinal use in the home.” Other ads claim it was just the thing for everything from “La Grippe” to “preventing serious developments,” whatever those might be, and one even goes so far as to depict a nurse handing a bottle of the whiskey to a bearded, bespectacled doctor, while noting that it was “the choice of a large majority of hospitals.” If you detect an odor of desperation here, you’re not wrong.

By 1907 Frick and his business partner and old friend Andrew W. Mellon, had applied to remove their names from A. Overholt & Co.’s distilling license, although their ownership of the company remained. It did not pay to be too closely associated with the “rum interest,” as the prohibitionists labeled their opponents. The window for making and selling fine whiskey was closing.

Then America entered the war raging in Europe. Suddenly, there was nationwide wartime Prohibition. You could still make whiskey, though, even if you couldn’t sell it—but grain prices were so high that it didn’t pay. The distillery suspended operations for the duration. In January 1919, however, two months after the guns fell silent, the 18th amendment was ratified. As if in sympathy with the old family business, Frick shuffled off this mortal coil a few months later, leaving his share of the company to Mellon, his executor. This ended the company’s family ownership.

The company did what it could. In 1918, it hired as many young women as it could find to run the bottling line, to flood the market with whiskey for those who were stocking up (they included Mellon; Christie’s auctioned off the last 50-odd cases of Old Overholt from his cellar last fall for as much as $18,000 a case). In 1920, distillery staff and federal gauging agents worked night and day to prepare 5,000 barrels of rye—two whole freight trains worth—for shipment to Philadelphia and from there to France, accompanied by the company’s director to make sure it sold. That doesn’t sound like all that much whiskey, but once reduced for bottling it makes almost 1.3 million fifths of rye. (What happened to those I have no idea, although there’s a good chance they were smuggled right back into the U.S.)

Fortunately, the Overholt company had managed to secure one of the small handful of permits the government issued for selling medicinal whiskey. The fact that Andrew Mellon was sworn in in 1921 as Warren G. Harding’s Secretary of the Treasury might have had something to do with that. The permit allowed them to bottle existing stocks of their whiskey and that from other distilleries (pint bottles only) and sell it to druggists, who would then dispense it to anyone with a prescription. There were numerous restrictions, but it kept the company alive. Meanwhile, its colleagues and competitors, Gibson, Guckenheimer, Hannisville, Mount Vernon and Tom Moore, all widely popular whiskies and benchmarks of quality, had to shut their doors. Only the nearby Large distillery secured a permit.

Not surprisingly, Prohibition’s proponents did not like the fact that the man in charge of the department tasked with enforcing it had an interest in a distillery and Mellon was forced to sell Overholt & Co. to the Union Trust Co. (of which he was a board member). In 1925, that company sold Overholt to New York’s Park & Tilford company, retail grocers (and, formerly, wine and spirit merchants) extraordinaire. That sale marked the end of Overholt’s local ownership. David Schulte, Park & Tilford’s president, promptly offered the U.S. Government all 1,800,000 gallons of the company’s stock at cost, to be bottled as medicinal whiskey. This wasn’t sheer altruism: The company hadn’t made any whiskey since 1916, and those barrels were getting older and woodier by the day. In any case, the offer was rejected.

In 1928 and again in 1931, permit holders were allowed to fire up their stills again. As Prohibition dragged on, the diseases that seemed to respond to pints of medicinal whiskey showed no signs of going away. Stocks needed replenishing. But here a fundamental shift occurred. In 1899, almost 375,000 gallons of whiskey were bottled in bond in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky; Pennsylvania rye made up nearly 38% of that, and rye in general just under half. During these distilling holidays, however, Overholt and Large, the two permitted Eastern rye distilleries, were only allowed a quarter of the total, while the rest went to Kentucky bourbon distilleries. This would prove a harbinger of things to come.

In 1932, with Repeal in the offing, Park & Tilford renovated and enlarged the Broad Ford distillery. Then, a few months later, it turned around and sold the brand, the distillery and all its whiskey to the industrialist Seton Porter, a canny Yale man who had family roots in the business. Porter saw Repeal coming before many of his contemporaries did and went around buying up closed distilleries and dead liquor brands while they were still cheap. When the great day finally came his National Distillers Products Co. owned more than 200 brands and fully half of the nation’s whiskey stocks. Only a few of those brands would be revived, however, and fewer still promoted. Old Overholt was one of them.

At first glance, things looked good for Abraham Overholt’s old enterprise. The distillery was running, his face was back on the label (which was virtually unchanged from the one before Prohibition) and sales were strong. Old Overholt was one of NDP’s big four flagship whiskey brands, along with a Maryland rye, Mount Vernon, and two bourbons, Old Taylor and Old Grand Dad. But now Overholt was a part of a portfolio, and its owners treated it accordingly. When stocks of four-year-old Overholt ran short, they filled some of the bottles with rye made at Large, one of six distilleries now operating in Pennsylvania and some with rye less than four years old. (Some said they even put Canadian rye in Overholt bottles.)

By 1938, such shenanigans had largely stopped. Broad Ford had pumped out the whiskey and socked it away, and now those barrels were four years old. Old Overholt went back to being a fully-bonded brand. But things weren’t quite right. One can tell by the neck bands on the bottles. Sure, Old Overholt’s main labels said “bonded,” and that was supposed to mean four years old. But as the 1930s edged into the 1940s, the bottles began bearing bands that touted the whiskey within as five or even six years old. Now, this sort of thing is very, very good for drinkers. It’s just not good for accountants, as it means that whiskey is sitting around unsold.

The old, thick-bodied, rich and spicy style of Eastern rye was falling out of popular favor. The drinkers who came of age during Prohibition were used to Canadian whisky and Scotch whisky and blended American whiskey. Straight bourbon still had a constituency (we’ll get into that), but the one for rye was shrinking with every passing year. The company may have tried to adapt its product to meet the trend: In 1941, a Consumer Union evaluator, tasting the current Overholt, thought it lacked the “characteristic brand flavor it one possessed” and found it “much lighter bodied.”

Even worse, now there was a war. The government immediately commandeered all the country’s distilleries to make industrial alcohol, essential for all sorts of useful, deadly things such as fueling torpedoes and making explosives. National Distillers parceled out their vast stocks according to the ration system, but even then it soon ran low. In 1942, Old Overholt launched a new, 86-proof version, for use in bars (the 100-proof was reserved for home sales). By 1944, American whiskey of any kind was practically as hard to find as Pappy Van Winkle is today. By then, victory was approaching and distillers were allowed to divert some of the torpedo juice to filling barrels, but that would take years to mature.

In the meanwhile, the public was given blended whiskey: a little of the aged stuff, cut with a lot of neutral sprits and water. This was meant to keep the whiskey drinkers sated until stocks of straight whiskey could rebound. However, funny thing, a surprisingly large part of that drinking public basically said, “You know, you can hold the whiskey part and just give us the neutral spirits and water.” Between 1949 and 1950 sales of vodka—i.e., neutral spirits and water—in the U.S. went up by 300 percent, and that kind of growth would continue through the decade. Meanwhile, the Overholt in the bottle got older and older—six years, seven years, eight years.

In 1951, NDP closed the stillhouse at Broad Ford, after just short of 100 years of operation, although it kept the warehouse and bottling lines open. (As far as can be determined, the whiskey that was going into those barrels and bottles then came from Large.) The company was losing interest in the whiskey business; indeed, it merged the next year with US Industrial Chemicals. In 1955, with Porter safely dead, they sold off Broad Ford and their last Maryland rye distillery, Baltimore Pure Rye, to the Schenley company to get capital for the chemical business. The next year, they sold the Large distillery to Westinghouse, who turned it into a nuclear research facility.

NDP kept the Overholt brand, though, and kept making the whiskey in Pennsylvania, although nobody is sure precisely where or how—whiskey distilleries were thin on the ground by then (the leading candidates are the Schenley distillery near Pittsburgh and the Bomberger one in Schaefferstown, some 200 miles to the east; it could have been made in both). Old Overholt still had its fans, though. One of them was Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who, according to a 1954 article, had an Old Overholt on the rocks every night before dinner, wherever he happened to be. To facilitate that, his plane was stocked with the whiskey, as were most U.S. Embassies. But Dulles was 66 years old in 1954; not a viable demographic on which to hang a brand.

There were at least some younger drinkers. Indeed, John F. Kennedy appears to have been one: When he was in Nashville in 1963, the owner of a local liquor emporium later recalled, he sent a man around asking specifically for a bottle of Overholt. If so, he was in a rare minority. By then, rye drinkers were getting truly scarce. NDP stopped advertising Overholt nationally around that time, sticking to the Pennsylvania market. In 1963, it adopted a still-lighter formula (“today’s Old Overholt is lighter, milder, smoother,” proclaimed the desperate ad that announced the change). The next year, it dropped the proof to 86. There has been no official bonded Old Overholt since. Some time around then, NDP began bottling the brand in Cincinnati, although the small quantities needed were still being made in Pennsylvania. At this point, it was the only nationally-distributed straight rye whiskey, such as it was.

Of the 1970s, there is nothing to say. Overholt struggled on. The Broad Ford distillery started to slide into ruin. Americans drank vodka, tequila and Bacardi Rum. In 1983, the old distillery burned, for the last time. In 1987, the National Distillers and Chemicals Corp., as it was now called, sold all of its spirits brands to a subsidiary of American Brands, the company that made Lucky Strikes. That subsidiary was the James B. Beam Distilling Co.

The first thing Overholt’s new owners did was consolidate its production, which is to say make it in Kentucky, according to Kentucky norms. Or maybe that was the second thing, after dropping the proof to 80, which happened by 1990. In any case, Overholt was no longer a Pennsylvania rye in anything but legend. Although it kept Abraham Overholt’s face on the label, there is no evidence whatsoever that Beam attempted to maintain any of his company’s particular distilling technologies, or even give Overholt its own mashbill. As far as anyone can determine (the company ain’t saying), Beam makes only one rye mashbill, and that’s the corn-rich one they have always used for their Jim Beam rye. (Eastern ryes traditionally eschewed the use of that grain.) Overholt was not a brand the company cared to emphasize.

There’s no reason they should have, not in 1987 or even in 1997. Beam is a Kentucky company, and it had enough trouble telling its own story and preserving its own Kentucky traditions. But if bourbon was struggling in the last decades of the 20th century, and it was, at least it stood for something. Its image was traditional, agrarian, ornery, and insurgent.

Rye—well, some time in the mid-1990s, I found myself watching a Fourth of July parade in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, in the northeast corner of the state. Among the marchers was a little clutch of high school boys and girls clad in the jaunty blue uniform of the Grand Army of the Republic, waving a flag, rapping on drums and blowing fifes. In the crowd stood many of their peers, including a surprising number sporting the Confederate Stars and Bars in one form or another. These were kids whose great-great-grandfathers and uncles had fought and, all too often, died at Shiloh and Antietam and Fredericksburg and Cold Harbor to defeat that very ensign. That was rye’s problem, right there.

Rye whiskey has a heartland of its own, a place it comes from and an ethos it stands for. If bourbon and Tennessee whiskey were (in the popular imagination, at least) made up on hills, on the banks of creeks and down in hollows, rye was always a proudly industrial spirit, something made in smoke-belching factories by the railroad tracks in coal towns and mill towns and river towns. Its Bardstowns and Lynchburgs (pop. 361) were cities the ornery likes of Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Baltimore (pop. millions). It’s not a whiskey for gentlemen of elegant leisure to sip on the verandah. Sharp and stimulating, it’s a fuel for work and talk and invention.

When American heavy industry began to falter; when the Rust Belt became the Rust Belt, nobody found that sexy. What people found sexy was the independent, agrarian life—not to live it, mind you, but to dress it and fantasize about it. When I was in high school on Long Island in the 1970s, the boys all wanted to look like Gregg Allman and the girls like Carly Simon. I went to my senior prom dressed (OK, ridiculously) as a riverboat gambler, long hair, black Stetson, string tie, silver cane and all. I drank Wild Turkey bourbon, Jack Daniel’s, and Southern Comfort.

But that’s all different now. That smoke-rolling, steel-belching industrial Mordor is so far into the past as to seem sexy in its own way, and the cities of the Rust Belt are in full-blown revival. Rye whiskey itself is also in full-blown revival, although that revival is still too young and too tentative to completely embrace the spirit’s past; to make a sweet-mash whiskey from local Pennsylvania or Maryland rye (no corn, please) distilled in three-chamber stills and aged in heated warehouses on the banks of the Monongahela or the Potomac. That will come, I have no doubt, whether it’s from one of the area’s pioneering craft distillers, such as Wigle, Dad’s Hat, or Catoctin Creek, as they grow to meet demand, or—who knows—maybe even from Overholt itself.

That’s not impossible: Fortune Brands, as American brands renamed itself, spun off its liquor division, Jim Beam, which was later acquired by Suntory. The Japanese whisky company has its own rich heritage and knows the value of tradition and especially the value of quality.

Were they to focus on Overholt; to refurbish it and, more importantly, to reconnect it to its roots and its traditions by bringing it back to Pennsylvania, they would essentially own the whole category of rye whiskey. Hey, it could happen. (And if they won’t do that, maybe they can sell it to someone who will.)