From George Orwell to Patricia Highsmith, 10 great books written by pseudonymous authors. Carmela Ciuraru, author of Nom de Plume: A Secret History of Pseudonyms, picks her favorites.

1. The Lifted Veil

by George Eliot

Although her name is typically associated with masterpieces such as Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss, in 1859 Eliot (born Marian Evans) published this odd novella. It appeared less than three months after the publication of her first novel, the commercially successful Adam Bede, but it contained elements of Gothic horror and embarrassed her publisher. This is the story of a man named Latimer, who possesses clairvoyant powers, has visions of his own death, and falls under the spell of his brother's manipulative fiancée. It is the only first-person narrative that Eliot ever wrote. When The Lifted Veil hasn't been dismissed by critics, it has been ignored. Yet Eliot herself understood that this was "a slight story of an outré kind," material that was more readily associated with Wilkie Collins or Edgar Allan Poe. Even so, despite its supernatural aspects, The Lifted Veil is at its core, like Eliot's other works, a moral and spiritual investigation. Although this novella is no masterpiece, its brief chronicle of one man's alienation and sorrow is gripping in its own way. For his part, George Henry Lewes—Eliot's soulmate and the man who inspired her to adopt her nom de plume—was an unabashed admirer of The Lifted Veil. "You must prepare for a surprise with the new story G. E. is writing," he wrote to her publisher. "It is totally unlike anything he has written yet ... this story is of an imaginative philosophical kind, quite new and piquant."

2. Hocus Bogus

by Romain Gary (writing as Émile Ajar)

Described by translator David Bellos, aptly, as "one of the most alarmingly effective mystifications in all literature," Hocus Bogus (originally published in French as Pseudo) is a fake memoir, but not in the James Frey sense. This literary hoax, which first appeared in 1976, purported to be an autobiographical novel in which the mentally ill protagonist, Paul Pawlovitch, admitted to being the bestselling author Émile Ajar. Although Ajar's identity had been a source of much speculation in France, he did not exist: This name was actually a mask of Romain Gary, who was the real author of Hocus Bogus. Born Roman Kacew in Lithuania, Gary was rich and famous but felt bored as himself. (He was also disgusted by what he viewed as the cronyism of the French literary establishment.) He adopted "Émile Ajar" instead, but once his alter ego, like him, became a prize-winning author, Gary panicked and realized that he needed someone to play the role in public. For this he recruited a distant relative—Paul Pawlovitch—who happily obliged, and both men outwitted the media and the public. Eventually, though, Gary felt cornered by his lies. As a means of satisfying people's curiosity, he produced Hocus Bogus. "I wrote my books in various hospitals on doctors' advice," he admitted (falsely). "They said it would be therapeutic." This book, which sold only modestly, destroyed Gary's relationship with Pawlovitch, who was furious that Gary had used his real name in this faux confession and had portrayed him as a lunatic. Gary, who had succeeded in throwing people off his scent with Hocus Bogus, fell into a major depression. In December 1980 he committed suicide in his Paris apartment. Yet Gary had secretly written another account of his Ajar pseudonym—the full truth this time—and wanted it released only posthumously. Called "The Life and Death of Émile Ajar," this fascinating piece is reprinted at the end of the English-translated edition of Hocus Bogus. "I've had a lot of fun," Gary signed off. "Good-bye, and thank you."

3. Why I Write

by George Orwell

Writing in the Daily Telegraph in 2009, Jeremy Paxman praised the man he considered one of the 20th century's best essayists. "If you want to learn how to write non-fiction, Orwell is your man," he wrote. "The impeccable style is one thing. But if I had to sum up what makes Orwell's essays so remarkable is that they always surprise you." Perhaps there is no finer starting point than Orwell’s 1946 essay “Why I Write” (published as a 119-page book by Penguin). Orwell, whose real name was Eric Blair, opens by admitting that since the age of 5 or 6, he wanted to become a writer, and that although he later attempted to abandon this idea, "I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books." Part memoir, part manifesto, “Why I Write” is an instructive critique of bad writing: "This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose," he writes, "and especially of any kind of political writing." He assails worn-out metaphors and pretentious language, urging writers to change bad habits and toss out "verbal refuse.” The essay includes four essential questions for "scrupulous" writers to ask in crafting each sentence: "What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?" And he cites four motives behind the writing impulse: sheer egoism, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, and political purpose. (These motives coexisted within the author himself, of course.) Orwell was at his best when expressing outrage, and in that regard, "Why I Write" offers no shortage of gems: "Political language," he writes, "is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind."

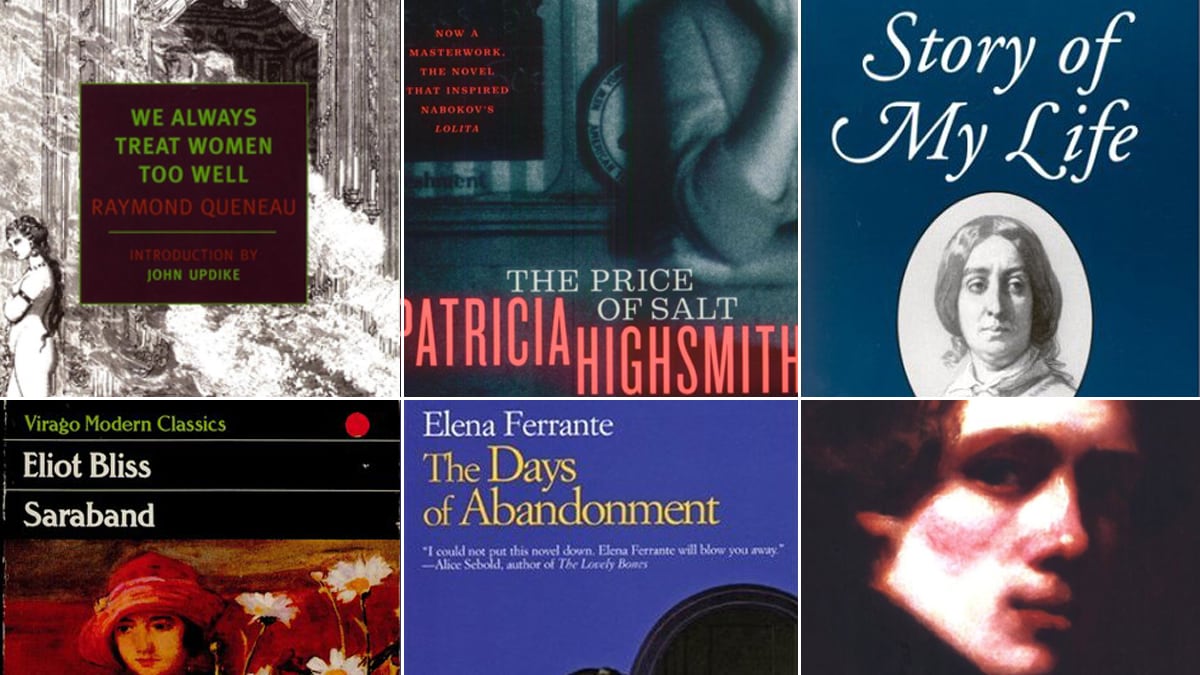

4. We Always Treat Women Too Well

by Raymond Queneau

When this slim novel was published in 1947 (On est toujours trop bon avec les femmes), its author was "Sally Mara," said to be a young Irish writer. But this was a work of pulp fiction by the modernist Raymond Queneau, who did not wish to harm his otherwise respectable reputation with what he regarded as a casual experiment. Until 1962 this book was omitted from the official edition of Queneau's works by his publisher, Gallimard, and it has been widely dismissed as "an unfortunate but forgivable interlude in a distinguished man's career." WATWTW, with its Joycean references (drawn heavily from Ulysses), must be read with a healthy appreciation for black humor. Otherwise, what to do with sentences such as "The dead doorman vomited his brains through an eighth orifice in his head, and fell flat on the floor"? Or the description of a character standing "with a heavy heart, a lumpy throat, an empty stomach, a dry mouth and a glassy eye"? Set in Dublin during the 1916 Easter rebellion, the story follows the blonde, lascivious Gertie Girdle. When rebels take over a local post office, she becomes a hostage and an unlikely heroine. (Her seduction skills can only be described as heroic.) Anyone with a penchant for the absurd will savor Queneau's farcical mingling of violence and sex. If, as critics have charged, this is a novel done in extremely poor taste, it is "a calculated act of literary sabotage," as one translator has noted, and "startling and ingenious." Above all, it is very funny.

5. Story of My Life

by George Sand

Although this iconoclast is recalled more for her cross-dressing, cigar-smoking ways than for her writings, in her lifetime George Sand was an influential and celebrated author—not just in her native France but throughout Europe. Her long list of admirers included Oscar Wilde, Henry James, Victor Hugo, and her close friend Gustave Flaubert. In the 19th century she was more famous than Charles Dickens. Charlotte Brontë, an admirer of Sand, described her work as "clever, wicked, sophisticated and immoral." And Dostoevsky once recalled that in the 1840s, "in our part of the world, [readers] knew that George Sand was one of the most brilliant, the most indomitable, and the most perfect champions ..." Born Aurore Dupin, Sand was incredibly prolific, publishing more than two dozen plays and nearly 60 novels, along with hundreds of essays and reviews and thousands of letters. Perhaps her most enduring work is Story of My Life (Histoire de ma vie), which is as much a chronicle of France as a history of her own remarkable life. One of the book’s most notable characteristics is Sand’s expression of her profound vulnerability—something hard to reconcile with her bold, rebellious public persona. "My melancholy thus came from sadness, and my sadness from suffering," she recalls of a difficult period in her 20s. "From there to disgust with life and desire for death was but a small step. My domestic existence was so gloomy, my body so overwrought by a continuous struggle against overwhelming pressure, my brain so tired from thoughts too precociously serious and by reading too absorbing for my age that I ended up with that grave moral disease—attraction to suicide."

6. The Days of Abandonment

by Elena Ferrante

The author is one of Italy's most acclaimed contemporary writers, yet no one seems to know who she is. Ferrante is said to have been born in Naples, but beyond that fact (if it is even true), she—or he—has remained private. The Days of Abandonment, her exquisite second novel, became a bestseller when it was published in Italy in 2002; it has since been translated into more than a dozen languages. Ferrante explores themes prevalent in her other books, including grief, desire, and guilt—all of which are treated with harrowing candor. If her material is remotely autobiographical, it might explain her use of a pseudonym. (Her debut novel was called L'amore molesto, or Nasty Love.) This story charts the descent of a middle-aged woman, Olga, following the abrupt departure of her husband, Mario: "One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me." She attempts to avoid a breakdown: "Don't give in, I said to myself, don't crash headlong." That Olga is the mother of Mario's two children seems to indicate that her wound will be made permanent: "How much of him would I be forced to love forever, without even realizing it, simply by virtue of the fact that I loved them?" she says. "What a complex foamy mixture a couple is. Even if the relationship shatters and ends, it continues to act in secret pathways, it doesn't die, it doesn't want to die." Beautifully translated into English by Ann Goldstein, The Days of Abandonment is a stunning, almost unbearable account of anguish, yet it offers redemption, too. Olga's recovery is hopeful without being sentimental: "Existence is this, I thought, a start of joy, a stab of pain, an intense pleasure, veins that pulse under the skin, there is no other truth to tell."

7. The Book of Disquiet

by Fernando Pessoa

It's one thing to adopt an alter ego or two, but the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa inhabited more than 70 different identities. He referred to them as "heteronyms" because he considered them separate from himself, claiming that he had no control over their literary production. "My imaginative world has always been the only true world for me," he once wrote. The ultimate self-deconstructionist, Pessoa, who died in 1935 at 47, claimed that he had not written The Book of Disquiet, but that an unassuming bookkeeper named Bernardo Soares (a "semi-heteronym") was the author, and had left him the manuscript. This book reads like a series of ontological and philosophical sketches, chronicling loneliness, yearning, and the meaning of selfhood. "From so much self-revising, I've destroyed myself," he writes. "From so much self-thinking, I'm now my thoughts and not I. I plumbed myself and dropped the plumb ..." It is a book of intimate confessions, yet its honesty seems universal rather than personal. "Everything that exists perhaps exists because something else exists," he writes. "Nothing is, everything coexists—perhaps that's how it really is."

8. Saraband

by Eliot Bliss

Published in 1931, when Bliss was just 28 years old, this coming-of-age novel chronicles the intellectual and emotional awakening of a shy, sensitive girl named Louise "Louie" Burnett, who spends her days in a dreamy world of her own. "Whenever she went out for a walk by herself," Bliss writes, "smelling the cold air all along the road, with the trees stark and white on either side, the exciting feeling took hold of her, the feeling that at any moment she was going to meet somebody or something." Like the dance referred to in the novel's title, the narrative is slow-moving but builds in its resonance and power as it moves along. The author's real name was Eileen Bliss, but she adopted the name Eliot from George Eliot and T. S. Eliot, both of whom she admired. Bliss worked in publishing, for Faber & Faber, counted among her friends Jean Rhys and Vita Sackville-West, and wrote only two novels (both neglected in her lifetime). She died in Hertfordshire, England, in 1990.

9. Party Going

by Henry Green

To call this a novel about nothing is almost an overstatement. Henry Green, the pseudonym of Henry Yorke, was fairly perverse in his insistence on disorienting readers and depriving them of relatable characters and tidy conclusions. (Nor was he interested in the notion of a linear narrative.) "Life," Green once said, "is one discrepancy after another." Party Going follows a group of spoiled, rich young people stranded one evening at a London railway station during a thick fog. (Green, who came from a wealthy family himself, despised social privilege.) Nothing much happens. His characters are given to banal musings and indecision. Desire is thwarted by inaction and overanalyzing: "[W]hile she had wondered so faintly she hardly knew she had it in her mind or, in other words, had hardly expressed to herself what she was thinking, he was much further from putting his feelings into words, as it was not until he felt sure of anything that he knew what he was thinking of." One of the pleasures of reading Green is his insistence on incomprehension, his dizzying sentences (with their strange syntax and oft-missing articles), and his peculiar brand of humor. Although Party Going is not "about" anything, it serves to reveal the banality of existence and the failures and mysteries of human interaction.

10. The Price of Salt

by Patricia Highsmith

A lesbian romance with a happy (or at least hopeful) ending was unheard of until The Price of Salt, a novel by Claire Morgan, appeared in 1952. The story of Therese, a clerk at a New York City department store, and Carol, the elegant, married woman whom she meets one day and falls in love with, was somewhat autobiographical. It was based on the author's own brief encounter with a beautiful blonde customer while working at a department store during the Christmas holidays. (In real life, however, no romance had occurred.) But "Claire Morgan" was actually the 31-year-old writer Patricia Highsmith, whose debut novel, Strangers on a Train, had been released two years earlier to great acclaim. The Price of Salt was nothing like the crime and suspense fiction that would make Highsmith so famous. Determined to avoid being labeled as a "lesbian" writer, she would not acknowledge her authorship until the 1990 U.K. edition of the novel appeared. The Price of Salt had been written in a fit of inspired passion. "It flowed from my pen as if from nowhere, beginning, middle and end," she recalled. "It took me about two hours, perhaps less."