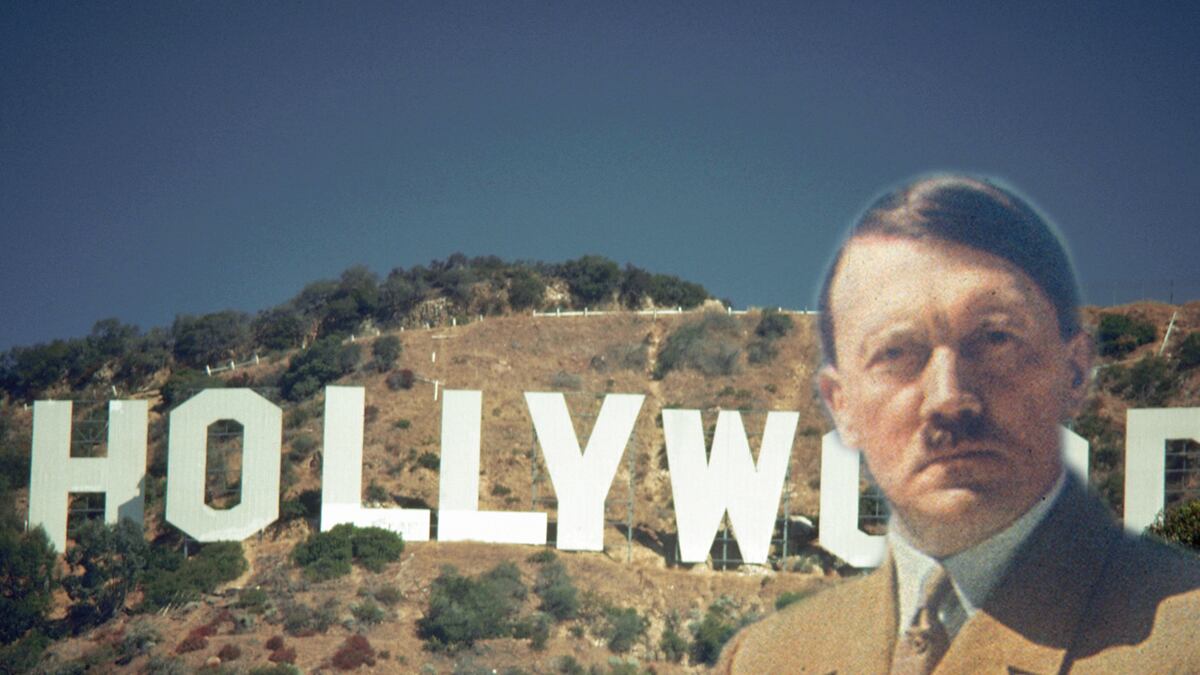

The cover story of The Hollywood Reporter’s August 9 issue examines excerpts from “The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact With Hitler” in which historian Ben Urward examines the relationship between Hollywood studios and films and the Nazi regime controlling Germany at the time. The book draws on newly discovered documents that reveal the measures studios took to make sure they wouldn’t be locked out of the very lucrative German movie-going market. Here, The Daily Beast examines some of the craziest revelations and explanations from the article.

1. It started with the cut of All’s Quiet on the Western Front

In 1930, Universal Studios released the movie based on the German book of the same name, All’s Quiet on the Western Front, about German soldiers during World War I. The film contained strong anti-war themes and was perceived by Nazi officials to have anti-Nazi messages. Master of propaganda Joseph Goebbels decried the film and he and a group let mice in the theaters and set off sink bombs to cause evacuations. As Germany was a large market for movies, Universal Pictures president Carl Laemmle agreed to make cuts to the film to be more palatable to German audiences (the film was restored to the original version by The Library of Congress and can be seen as an extra on DVDs). German officials found out the uncut version was still playing in El Salvador and Spain in 1932, causing Universal to pull the uncut movie from those countries and apologize for the oversight. Other studios soon followed making concessions in regards to films to the German government and beginning in 1933, Hitler’s representatives.

2. Studios worked together to shut down a movie about the treatment of Jews in Germany

In 1933, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (who would go on to pen Citizen Kane) started work on a script for a movie called The Mad Dog of Europe about the deplorable treatment of Jews in Germany, in partner with a friend Sam Jaffe. The picture was to be produced independently and thus wasn’t under the constraints of major studios or their agreements with the German government. Incensed, German officials went to the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, which regulated sex and violence in movies and threatened to ban all American made movies in Germany if Mad Dog were made. The movie outline was modified to feature a fictious country and tone down some of the propaganda elements, but it was turned down by agents saying no studio would take it for fear of upsetting film interests in Germany. Jaffe sold the rights to agent Al Rosen, but after being unable to find funding, the movie died without being made.

By 1936 Nazi censors were rejecting so many films left and right that only the largest studios bothered to have a continued presence in Germany, GMG, Paramount and 20th Century Fox.

“Over the next few years, the studios actively cultivated personal contacts with prominent Nazis. In 1937, Paramount chose a new manager for its German branch: Paul Thiefes, a member of the Nazi Party. The head of MGM in Germany, Frits Strengholt, divorced his Jewish wife at the request of the Propaganda Ministry. She ended up in a concentration camp.”

3. Eventually anti-Nazi films were made, but only after it became profitable

In 1937, while plans for The Road Back, the sequel to Alls’ Quiet on the Western Front, were being made, Georg Gyssling, Hitler’s personal consul in Los Angeles, sent letters to 60 people involved in the film's production warning them their participation in the film would lead to any film they would work on in the future being banned in Germany. Universal rushed to edit the film, making so many cuts that by the end the plot was nonsensical and still displeased Nazis, resulting in a ban on Universal films. By the time the third film in the trilogy, Three Comrades was being filmed, MGM had to screen the film to Gyssling first and then answer to a list of changes and requirements given to them by him.

As the war continued the studios found that their concessions to Germany was costing them viewers in England and France. They decided to switch their focus to the more lucrative markets, began making anti-Nazi pictures and were expelled from German-occupied territory in 1940.