At precisely noon on Nov. 21, 1918, the whistle sounded. All across San Francisco, people pulled the masks from their faces and threw them into the streets, at last free. In the Bay Area, unlike in Los Angeles, officials had made the coverings mandatory for anyone in public.

The celebration was premature. While cases of flu had fallen, this turned out to be only a temporary ebb, and by January the infection rate had resurged. The virus continued to spread. In San Francisco, the daily cases reached 600 and kept climbing. Authorities reinstated the citywide ordinance and the masks returned. As supplies ran low, residents used chiffon and linen. The San Francisco Chronicle reported people covering their faces with “fearsome looking machines like extended muzzles.”

It wasn’t until February, after 3,000 people had died and the infection rate had fallen again, that the health department deemed it safe for the city’s residents to rid themselves of the hated masks once and for all. Finally, they could breathe freely.

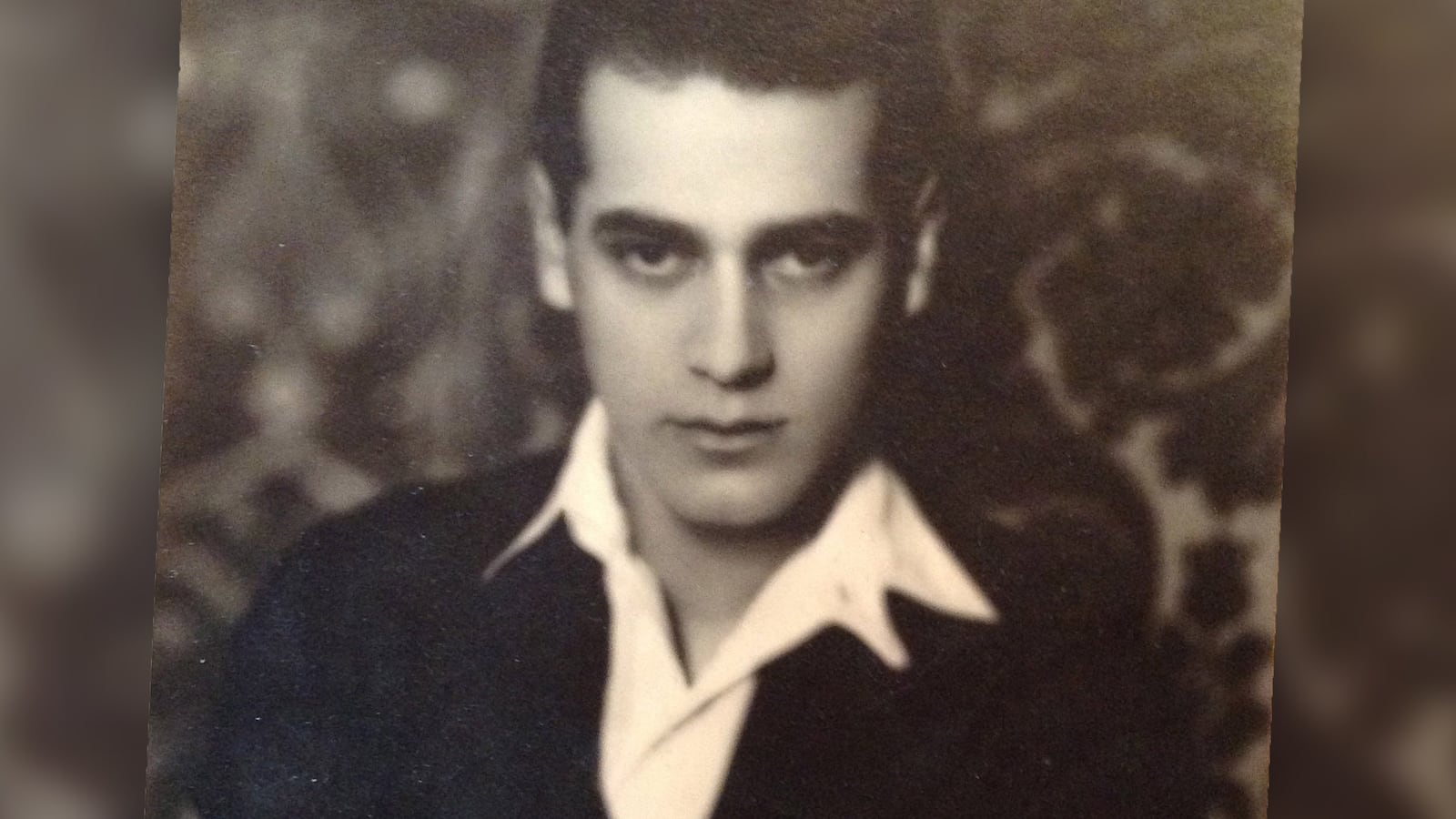

Except for the dark-haired shop clerk. The gauze was gone, but Albert Weis Harrison still wore a mask, the one that all temperamental men wore. They watched for one another on the streets, lingering at shop windows, glancing back once, and then again. But as the circuit of signals began, they couldn’t be certain they weren’t stepping into a trap with an undercover cop looking to make an arrest or 20-dollar shakedown. The shadow worlds, like hotel lobbies and the Sultan Turkish Baths—“devoted to the comforts of men”—were filled with double agents. It was safer to gather in someone’s home. At least it had seemed so until the police department’s so-called morals squad staked out the house of Hugh Allen, a music teacher who hosted parties in his studio on Baker Street.

San Francisco has always been a small town where degrees of separation can be minimal to nonexistent. Albert lived on Clay Street, a few blocks away from Hugh Allen, so he may very well have known the music teacher or any of the thirty-some men now on trial for violating Section 286 of the California Penal Code, or engaging in sodomy, a crime that carried a penalty of five years to life in prison. Even a misdemeanor charge of “conspiracy to commit acts tending to lower the morals of the community” could result in a prison sentence, not to mention public ruin.

Albert did, in fact, know the wealthy bon vivant Dick Hotaling, son of distiller A. P. Hotaling, whose whiskey warehouse was famously one of the only waterfront buildings to survive the 1906 earthquake and fire. Hotaling was called to testify, but he was never accused of any crimes. If Albert did know the accused men, he was lucky indeed. Hugh Allen had fled to Honduras. When police arrived at the house of an accountant who’d been named in the scandal, the man shot himself in the head.

Providence had a strange way with the young shop clerk, so slight and small at 22 that sometimes he still seemed a boy. On June 22, 1916, the San Francisco Chronicle had published a news story headlined:

TWO DRUGS USED BY YOUTH TRYING TO END HIS LIFE

The article went onto to report all that appeared to be known about Albert Weis Harrison at that time: that he’d taken a room at a hotel on Taylor Street, that his father had died earlier that year, and that he’d briefly attended military school in Marin County, where he was said to have been “temperamental, moody and morose.”

“Temperamental” was code, and its appearance in the news item about Albert’s suicide attempt was surely not a coincidence. A German immigrant caught in the Baker Street raid was perplexed when asked to explain its meaning:

“A: What I understand—I don’t know if it is. A person is temperamental if they enjoy or love beautiful things, art, music, or any of that kind.”

Another defendant, a soldier who was being held on Alcatraz while waiting court martial, lost his patience at the term’s deliberate obscurity:

“A: Well, to use that word—whatever it means—Why don’t you use the good old word ‘perverts’ and be done with it?”

Pervert wasn’t a word to be used in polite company. Temperamental was, although of course both the German immigrant’s and the soldier’s definitions could be true. A man could love art and music and he could have sex with other men, but, as Oscar Wilde had brutally learned, the court cared only about the latter.

There’s no way of knowing what brought Albert to his bleak decision in the hotel room, whether his circumstances were similar to the ones facing the men on trial or whether his actions stemmed from another kind of despair.

Albert’s childhood had been a precarious scramble. His mother was the daughter of Albert Weis, an immigrant from Strasbourg who’d parlayed a Galveston dry goods business into a thriving theatrical empire in the Gilded Age South. That was his namesake and yet Albert wasn’t born into wealth but into its memory—and into chaos. His father, Mark Harrison, was a charismatic, volatile clothing salesman, who carted the family up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Albert’s early years were a blur of new siblings and new towns until one day, when he was three, his mother was suddenly gone and he alone with his father and his sister Gladys in the fishing town of Gloucester. And then one day Gladys, too, was gone. “A brilliant man, but a drunkard,” he would later write about Mark. Of his mother, he noted simply, she “was very pretty as I remember her.”

He’d chosen none of it. Not his name, not his life, not his family, not his father’s death in Sacramento. He hadn’t chosen the boardinghouses as he hadn’t chosen the military school. However, in 1916 he chose to put an end to Albert Weis Harrison. And yet fate had other plans. In his determination to end his life, Albert took a second poison and inadvertently saved himself.

Fortune had found Albert at last. He escaped the Baker Street dragnet, avoided the war, and survived the influenza epidemic that had killed millions of young people. And now luck struck once more. The door of G.T. Marsh & Company swung open and in walked Albert’s newest customer, William Andrews Clark Jr.

It’s a bitter realization that in excavating queer lives we so often excavate the loathing for those lives. In combing through crime reports and editorials for traces of marginalized existences, we enter a world shot through with scorn and prurience. In trial transcripts, we don’t find people but “degenerates” and “perverts.” We know tragedy rather than joy. We know the date that Albert took two poisons to try to kill himself at the hotel on Taylor Street but not the date that Will stepped into the Orientalist boutique at the corner of Powell and Post.

It was sometime in 1919. Three years had passed since Albert’s suicide attempt. The despair had broken. Now he lived near the Presidio with an older woman named Mary Post. She was a kindly widow in her sixties with dark eyes and dark hair that she wore pulled back in a bun. Her children were grown and scattered, and Albert had become her foster son. She was, as he recalled later, “a charming old lady and a brilliant one.”

How Mary Post and Albert Harrison came together is one of the enduring mysteries of his story. By the time he took the job at “the Marsh,” as he called it, he was already living with her. Many would assume that his later name was a fiction, but “Harrison Post” was the truth of whom Albert had been and whom he became. He was still very much his father’s son. The mercantile world was his legacy, and his brief career as a salesman would set the course of the rest of his life.

In Sacramento, his father had dressed state lawmakers and businessmen. Now at the Marsh, Albert tended to another level of power. His customers were the kind of people who saw to it that the men in Sacramento did their bidding. In some cases, the clientele were the children of those elites, and though they may not have amassed the capital, they spent the dividends at places that catered to those who could afford to alight anywhere in the world, provided there were palace hotels, chauffeured cars, and a solicitous staff at their disposal. These were people whose homes were dictated by season, such as the widowed son of a copper baron, who spent spring in Los Angeles, summer in Montana, and winter in Europe.

Surely when Will entered the store, the young clerk already knew his customer’s background—knowledge of the rich and powerful was part of the job. Albert likely knew that Will’s wife Alice had died the year before and that the Clark family had recently suffered another tragedy. In early August, Will’s half-sister Andrée fell ill with meningitis. The 16-year-old died within a few days. The shocking loss crushed her parents and her little sister, Huguette, and the grief-stricken family had taken refuge at Will’s lodge on Salmon Lake.

Whether Albert immediately identified the well-dressed older man with chestnut hair, his new customer may have stood out in another way. That year, Will had broken his arm playing golf and been forced to wear a cast.

Often guarded and reticent, the senator’s son wasn’t considered an easy man to know. A photo taken by Edward Weston shows Will, thin-lipped, standing against a wall, holding a cigarette tightly, a recoil in his glance, waiting, it seems, for the viewer to look away. The Weston portrait Will preferred was of him seated, in profile, not looking at the camera but lost in the pages of a book.

There were many things that put Albert outside Will’s orbit—among them his merchant class and his Jewishness. His early years with a peripatetic salesman father bore little relation to Will’s opulent childhood. The legacy of wealth that did exist in the clerk’s family had closed ranks without him. Albert’s existence wasn’t secured by mineral assets and land holdings. His life was suspended by slender threads, the fairy-tale benevolence of Mary Post and his position at the Marsh.

Founded by George Turner Marsh, an immigrant from Australia, the “Japanese Art Repository,” as the store was often described, first opened in the Palace Hotel, the same hotel that had welcomed Oscar Wilde in 1882. After the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed the building and the original store, Marsh reopened at Post and Powell streets. Often considered one of the earliest purveyors of Asian art and furnishings in the United States, he was also one of the first retail merchants to bring his wares from behind the sales counter for display out in the open on long tables.

The Marsh was a store that invited its customers to linger and touch, to pick up the celadon-glazed charger plate from the Ming dynasty or the teacup of porcelain so thin it would’ve made Wilde swoon. Albert didn’t stand behind a counter but instead at Will’s side while the two ambled through the shop, discussing history and craftsmanship. Perhaps the conversation broke into other topics. For instance, that year the Metropolitan Opera was celebrating Enrico Caruso’s 25th year in opera. Albert loved the tenor’s voice.

It’s the salesclerk’s job to draw his customer out. He learns about the patron’s life—his travels, the books he reads, what he finds beautiful, what he wants in his home. If two men hold eye contact longer than usual, it’s not necessarily cause for suspicion—unlike, say, a second glance in a public washroom.

Although the younger man had been raised in rented rooms, he possessed a distinct worldliness. Will could recognize the clerk’s cosmopolitan air, even if it didn’t come from living in Paris among tutors and nannies.

Albert was accustomed to admirers—men and women. He enjoyed both, though he preferred men. Of course, like his introverted customer, he was well aware that male attention could come at a cost. They may have belonged to different classes, but they wore the same mask. When it came time to draw up the bill, if Will in fact bought anything that day, the two men were on opposite sides of the sale. Still, a transaction is a point of contact. Inside the Marsh they were safe. No stool pigeons, no shakedowns. At the intersection of wealth and commerce, shopping offered cover for two men to fall in love.

On Oct. 1, 1919, the shop clerk boarded a train bound for Los Angeles. He was joined by Will, a society friend, Will’s major domo, and a Boston terrier named Snooks. In the years to come, traveling with an entourage would be customary—not only so there was someone to manage luggage, bookings, and other matters, but also to obscure the nature of the relationship between the two men.

The small party arrived at the new Central Station on Fifth Street. The Arcade Station, which had trapped exhaust from the locomotives, had been torn down. When he alighted from their car, Albert wasn’t greeted by grime and soot but a soaring lobby and 14 one-ton chandeliers glimmering above.

The copper scion had been reckless after his first wife Mabel’s death, and now after Alice’s, it seemed, he was again. It was unquestionably rash to begin a romance with the 22-year-old shop clerk. But Will’s wildness—if that’s what this was—took a different form from that of his earlier libertine years. Rather than dissipation, Will had entered a phase of expansion.

On June 11, 1919, he had announced that he would spend $200,000 to launch a new orchestra in Los Angeles, followed by $150,000 for each of the subsequent five years to maintain it. This wasn’t the city’s first. The Los Angeles Symphony had been established several years before, and Will had been invited to join forces with the existing institution, but differences had arisen. Like his father, he preferred to forge on alone.

By 1919, Los Angeles had been through several boom and bust cycles. Land speculation crazes had fallen away before, but the latest growth spurt, fueled by a steady influx of immigrants from the heartland, showed no sign of abating.

It’s a familiar song, as old as Los Angeles—the lamentation about the dearth of culture, a purported wasteland compared to other cities. Writing for The Smart Set in 1913, Willard Huntington Wright bemoaned the refugees from the prairie not because they disrupted an established way of living, spoke in strange tongues, or kept unfamiliar customs, but for failure of imagination:

<p>These good folks brought with them a complete stock of rural beliefs, pieties, superstitions, and habits—the Middle West bed hours, the Middle West love of corned beef, the church bells, Munsey’s magazine, union suits and missionary societies. They brought also a complacent and intransigent aversion to late dinners, malt liquors, grand opera and hussies.</p>

If the newcomers filling up the bungalows lacked zest, those coming to make the “flickers” had plenty—perhaps too much. The nascent motion picture industry wasn’t populated by the folks but freaks. By journalist Carey McWilliams’ count, this included “dwarfs, pygmies, one-eyed sailors, showpeople, misfits, and 50,000 wonder-struck girls. The easy money of Hollywood drew pimps, gamblers, racketeers, and confidence men.” Between the provincial Middle Westerners and the outlandish movie colonists, Los Angeles was found wanting. Obviously the town knew entertainment—Sid Grauman had just built the Million Dollar Theatre on Broadway—but Will was determined that it should have culture too, or, to use a term his young lover liked, “tone.” They were separated by 20 years, but the two men possessed the same recoil when it came to vulgarians.

That summer Will moved fast. A month after his announcement, he hired Englishman Walter Henry Rothwell, a former apprentice of Gustav Mahler, to be the conductor. His first choice, Rachmaninoff, had declined.

Will’s secretary Buck Mangam would later contend that the creation of the Los Angeles Philharmonic was a bribe. To Mangam’s thinking, it was a preemptive measure on Will’s part, a bid to ingratiate himself with the city leaders and to deflect attention from his homosexual life. The secretary couldn’t countenance that Will might’ve been acting with the public good in mind, though it seems unlikely that Will would have funded as many free concerts as he did if he didn’t care about public good.

And yet Buck may not have been entirely wrong, that Will’s new romance was connected to his sudden cultural efflorescence. Even if Will wasn’t spurred by civic selflessness, he may have been acting out of an impulse that had nothing to do with fear and that in making one aspect of his life secret, he was compelled to expand into other realms.

A trained violinist, Will wasn’t a stranger to artistic expression, but he also didn’t identify himself as an artist. And while he may have wished to be a great conductor, he didn’t mistake himself for one, readily ceding decisions to Rothwell and the other conductors he hired. Still, Will Clark did produce the circumstances for artists to create, and he made their work available to the public. In this, his patronage was a creative act. But regardless, he didn’t have to be an artist to have a muse. Will was a man in love, emboldened to make grand gestures, like hiring a conductor and 90 musicians, leasing an entire building, and selling tickets to the whole town.

The rain started early on the morning of Oct. 24. It was still coming down that afternoon when two thousand people gathered outside the Trinity Auditorium on the corner of Grand Avenue and Ninth Street for the debut of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Albert was among those jostling umbrellas and overcoats, pressing their way into the beaux arts building, and yet he was separate.

Just a month ago he’d been attending to the wealthy, an attractive young man polishing their brilliant sphere. Now not only had he penetrated that world, but as the guest of the man who’d financed Los Angeles’s new orchestra, he belonged to an even more elite milieu. He floated past the masses, up to the auditorium’s luxury loges, taking his seat among the Dohenys, Flints, Barlows, Sartoris, and Clarks, the burgeoning aristocracy of bankers, oil barons, real estate tycoons, and society matrons.

It was a momentous undertaking on Will’s part—launching an orchestra, and in only four months. He’d been decisive but hasty, and there hung the unspoken but real possibility that this would be a scorching disaster, a rich man’s folly, and not just the usual stumble, like Will’s brother Charlie losing again at the races, but failure on a massive and public scale.

From the back of the stage, a gong rang out, shuddering through the floorboards, and the ninety musicians, all in white tie, marched out from the wings. Ten double basses. Violins, violas, cellos. Next, the horns. Then came Walter Henry Rothwell in black tails, spectacles glinting. The applause surged. At the podium, Rothwell bowed to the audience, pivoted back to the men now seated with their instruments, and raised his baton.

The strings started first, then came a flourish from a horn. The woodwinds answered, soft, tentative, almost a pause, before the return of the strings and the crash of the kettledrums. They’d begun with Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9.

For a moment, it seemed that the auditorium spun. Onstage, the bows danced and dipped. The music rose again—strings, horns, a ribbed sound, then the woodwinds, soft and gliding. It’s often referred to as the New World symphony, but Dvořák actually titled the work From the New World—a significant distinction. He’d composed it in 1893, one year after coming to America from Bohemia to direct the National Conservatory of Music in Manhattan. While he was inspired by Black spirituals and Native American melodies, Dvořák dismissed the popular belief that the symphony directly quoted those forms or that he was introducing Americans to their own legacy. He also drew deeply from Celtic and European traditions as well as the Slavic folk music of his native country. The symphony was not so much a celebration of America as it was the reverie of a traveler in a strange and vibrant land, longing for home, with lush and cyclic melodies that give way to an aching solo by an English horn.

A trombone caught the light, a flare flashed across the auditorium. Rothwell’s shoulders jerked and his arms spread wide, pulling sound through the air. Bohemia was gone now. Dvořák’s homeland, along with what had once been Moravia, was a new country called Czechoslovakia. The empires—Russian, Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman—had shattered into pieces.

The world had changed, and so had Albert. Just a month ago he’d been a salesclerk and now he was something else—anyone he wanted to be. He was 22, beautiful, beloved by a scion of Gilded Age wealth, alighting in Los Angeles on the cusp of Prohibition, the eve of the Jazz Age, as F. Scott Fitzgerald named it—or, in Carl Van Vechten’s words, “the splendid drunken Twenties.”

The war was over. People were alive. A new game was coming—a giddy, universal, adult hide-and-seek played with secret codes, speakeasies, fake bookshelves, whiskey in teacups, and flasks tucked into garters. The masks were gone—at least most were. It had been a cruel joke, a glitch in the universe, a young man sensitive to beauty, to finer things, and no means to possess them, as if born into exile. The air he’d breathed his whole life had been suffused with power and wealth, and yet both belonged to other times and other people—his mother’s past, his father’s customers, his own customers. But that was over. He was done with boardinghouses, done with the family who’d abandoned him, done with despair in a rented room. Now he had a new mask, one that fit him perfectly—wealth.

After the intermission, the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed Weber’s overture to Oberon, Liszt’s “Les préludes,” and Chabrier’s rhapsody “España.” When Walter Henry Rothwell concluded the program and turned to the more than two thousand people who’d gathered in the auditorium, he was met with unstinting applause and bravos.

Albert clapped, too, as the ushers streamed down the aisles bearing floral arrangements, including an enormous horseshoe of garlands—a collective tribute from the symphonies of Boston, Cincinnati, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and San Francisco. Los Angeles had arrived, and so had Harrison Post.

He slipped into his new self and into the new, loosening decade. He and Will may have been criminals, but soon enough everyone else would be too. Four days after the debut of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, on October 28, the Senate overrode Woodrow Wilson’s veto to pass the Volstead Act, enforcing the Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, and transportation of high-proof spirits. They were all in the shadows now.

It wasn’t a question anymore of ending himself but of becoming the man he was meant to be, and so he did. On December 6, 1919, a small item appeared in the Sausalito News under “Court Calendar”:

Application for Albert Harrison for change of name—Application is granted.

From TWILIGHT MAN by Liz Brown, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Liz Brown.