Forever ago in the mid ’60s, a sylph of a girl named Edie Sedgwick captivated the world—or at least Andy Warhol, and through his Factory and his films and his photos, everything and everyone else that mattered. She was the American art world’s “It Girl,” the source material for numerous plays, books, and movies, even the alleged inspiration for Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Perhaps that’s part of what inspired the name of the eponymous heroine in Adele Griffin’s addictive new YA novel, The Unfinished Life of Addison Stone. In a phone interview, Griffin says the book is, in part, homage to Sedgwick, whom Griffin stumbled upon as a child when a library mis-shelved the biography Edie: American Girl in between the Nancy Drews and the Hardy Boys.

“It sounds like it could have been a kid’s book, right?” says the two-time National Book Award finalist with a sly laugh. “But … I knew it wasn’t.”

Sedgwick has haunted Griffin ever since. “There was no one in my neighborhood who lived this kind of fabulous, decadent life,” she recalls of her childhood, which she spent mostly on Army bases. “It set my mind on fire.”

That blaze of childhood adulation burst into full flame in the character of Addison Stone, a post-millennial Edie Sedgwick who is “more gorgeous, more reckless, more tragic, more talented” than the original. And this time, she’s also her own Warhol, making her own art, creating her own image. Or as Griffin puts it, Stone is “Edie as Banksy,” referring to the British graffiti and installation artist whose work routinely pushes the boundaries of what high art is and says.

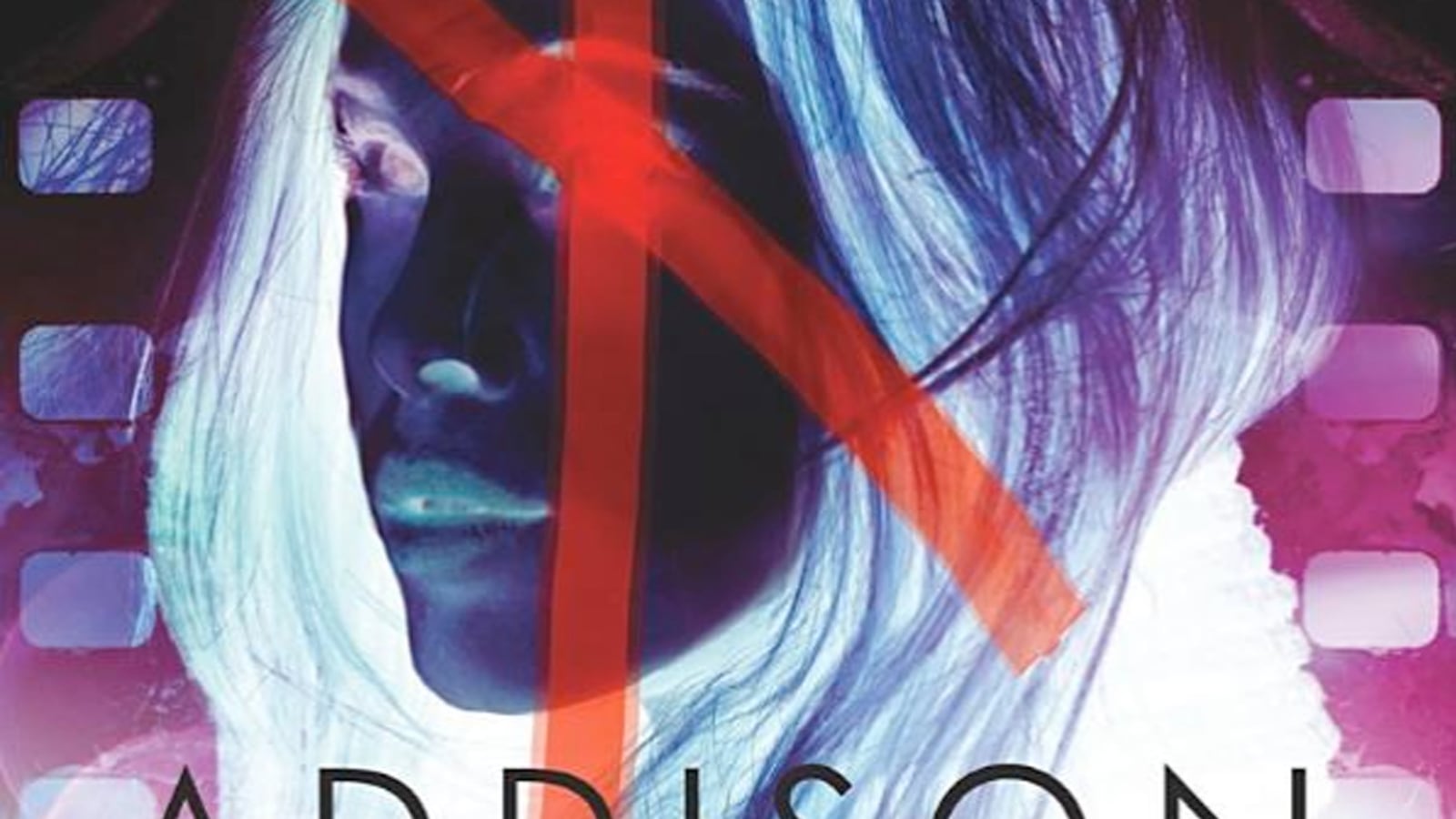

Griffin’s book pushes genre boundaries as well. Conceived of as a “docu-novel,” the story is told entirely in interview segments, as an attempt to reconstruct the meteoric rise and terrible fall (both literal and figurative) of Addison Stone. Griffin is herself a character in the novel, the invisible hand on the other end of the tape recorder in all the interviews. Stone is a precocious artist who goes from lower-middle-class suburbia, to the Whitney Biennial, to her own mysterious death in just a few short years. Along the way, she manages to pick up a Victorian ghost, a wealthy patron, a sleazy agent, two not-always-good-for-her boyfriends, and a cast of trust fund friends that one could easily imagine are the Rich Kids of Instagram.

The main challenge for Griffin was to imbue this art-world story with enough energy to work as young adult fiction, where everything is bigger, brighter, and more. “I needed less of my trip to Frieze with my husband,” Griffin jokes, and more of a young girl’s fantasy life. Luckily for Griffin, that life literally walked into her kitchen one day, when a friend brought over up-and-coming model Giza Lagarce.

“She was so stunning, and so … Edie,” Griffin recalls. “I thought, ‘More of that! More of that!’”

Lagarce became the embodiment of Stone, bringing with her not just her stunning looks, but her wealth of Facebook photos, which Griffin began to “write into” in order to breath the necessary life into the novel. She cites finding Lagarce as the “major rewrite” of the process, and the resulting meld of obviously real images with supposedly real interviews helps to further shatter the line between fake and fact in her story.

But Lagarce isn’t Addison Stone’s only real world analogue. Griffin mined the portfolios of four artists to create the vast collection of images that dot the book. The particulars of the plot, Griffin says, emerged from the interplay between the Sedgwick story she imagined, and the artworks that captivated her. Sophie, a minor character, was created specifically so that Stone could use a portrait by Michelle Rawlings of a young girl with a bloody nose—a portrait she now owns, along with a few of the other “Addison Stone” pieces from the book.

Yet despite all of the photos and paintings and interviews, Stone remains an enigma—this isn’t a mystery novel with a stunning twist at the end, which may disappoint some readers. The mystery here is Stone herself, not what happened to her. But what rises unexpectedly from reading the novel is a lesson that all teenagers would do well to learn: We are all of us mysteries. As characters debate the true nature of Addison Stone, they reveal just how little they know each other and themselves, and how much they project their own beliefs, fears, and hopes onto the world. Stone might shine a little brighter, take up a little more of the oxygen in the room, but she is no more mysterious than anyone else—there are just more people asking questions.