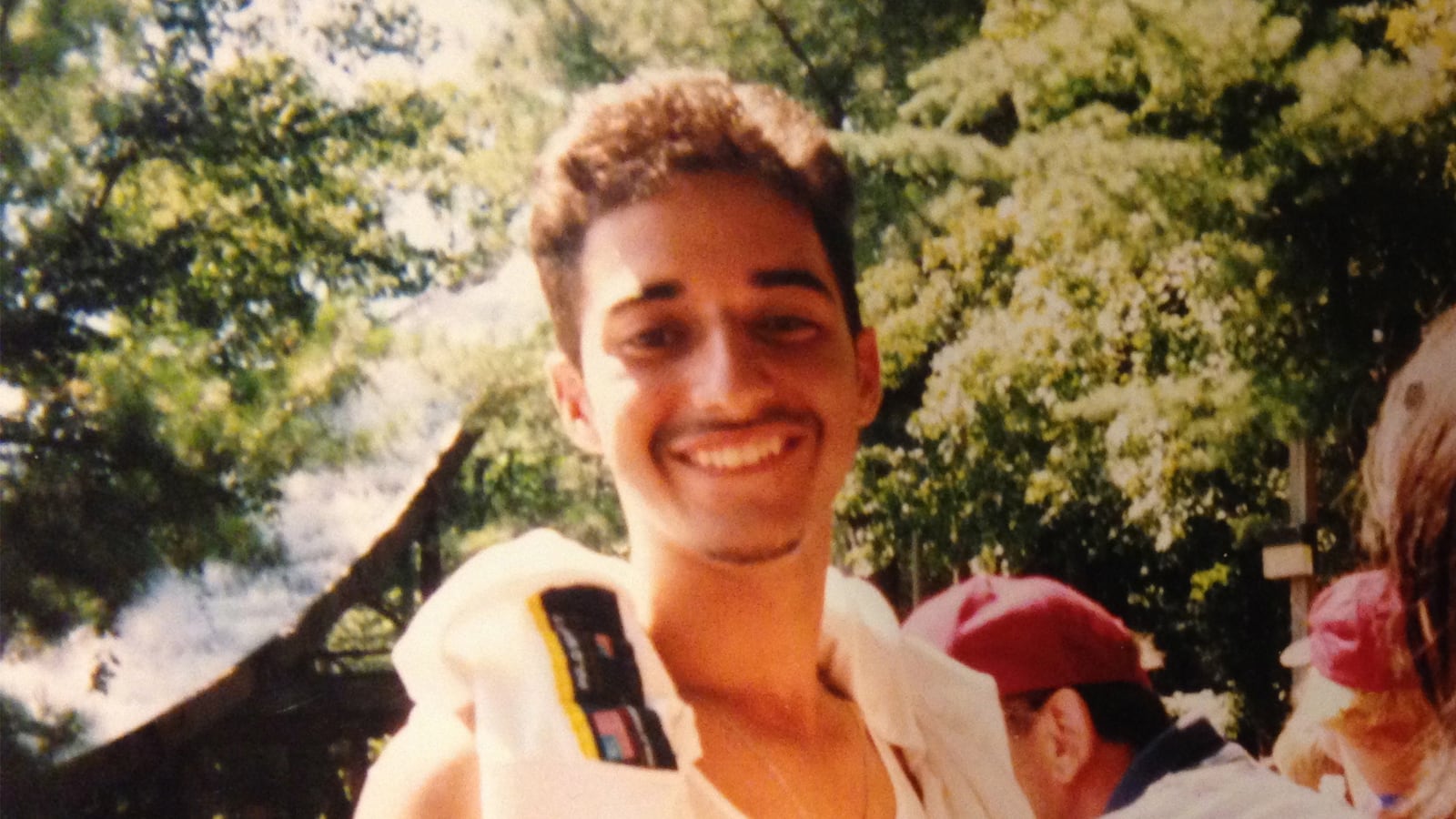

If you’re one of the five million people who downloaded Serial and have been obsessing over who killed Hae Min Lee over 15 years ago on January 13, 1999, you couldn’t have realistically expected an answer in the final episode. In the end, the show went all in, adding new information that only increased our doubts and, frankly, corroborated whatever you thought before the episode regarding Adnan’s guilt or innocence. Sarah Koenig embraced the ambiguity of Hae’s murder and Adnan’s trial. Yet admirably, she didn’t completely surrender to ambivalence.

For those of you haven’t listened yet to the series or the final episode, I don’t think it even warrants a spoiler alert to say that we still don’t know if Adnan or Jay or someone else killed Hae. If anything, the blurred lines only grew fuzzier. The alternative explanations for red flags in Adnan’s and Jay’s accounts only multiplied. Koenig and her producers dove into the Nisha Call and concluded a butt dial situation was certainly possible; that was another piece that could possibly help Adnan. But, it turned out the Best Buy where Adnan allegedly called Jay to pick him up after Hae’s murder probably did have payphones in the opening vestibule, which affirms some of Jay’s testimony.

We also heard (I use that term loosely) from a few new characters, one who could fall into quasi-support for Jay and one who could fall into quasi-support for Adnan. Koenig says Don, Hae’s boyfriend at the time of the murder, agreed to speak to her recently, though not to be recorded. The most interesting things he told Koenig was how much the prosecution ripped him for not speaking ill of Adnan on the stand. He said in both trials, prosecutor Kevin Urick “literally yelled” at him for not making Adnan sound more creepy. It’s pretty standard for a lawyer to want one of their witnesses to make the person he’s trying to convict look horrible, but Don’s unwillingness to do so and the prosecution’s treatment of him post-court testimony only increases our trust in Adnan.

Then, there’s Josh, a guy who worked with Jay at a porn video store. He recalled for Koenig how scared Jay was the night he was picked up by cops—though not of the police, but of Adnan. Jay apparently never told Josh Adnan’s name and was “afraid, almost in tears” with fear because the killer threatened him. Josh does say that the killer is a Middle Eastern ex-boyfriend, so it does match up to Adnan (He is from Parkistan, not the Middle East, but we can tell what he's getting at). This insight into Jay’s perspective certainly lends credence to Jay’s version of events and suggests Adnan is the killer.

However, Josh’s new information also raises questions that don’t necessarily support Jay or Adnan. Josh says Jay called him to come be with him at the video store the night the police arrived because Josh was under the impression Jay called the cops himself. He said Jay was anxious and wondering why it was taking so long for the police to arrive. If Jay had called the cops, why would he be so nervous? If he did call the cops, was it a way to confess his guilt for being an accessory to Hae’s murder or to build his credibility with police when they found out he was involved? Or, was it a way to start the wheels in motion for pinning Hae’s murder on Adnan.

Josh also corroborated what Serial listeners already had heard about Jay: he lies and he brags about things that he hasn’t actually done, which again, just leaves us more confused. When do we stop and start believing Jay, the person whose testimony upon which the state of Maryland relies? We know Jay was right about one important thing: where Hae’s car was located.

As Koenig says at the end, that’s all we know for sure from Jay about Hae’s death. The only thing we’ve known for sure since the beginning hasn’t changed. We began a journey with Koenig in the first episode of Serial. Perhaps, we didn’t think we’d find out for sure if Adnan was innocent or if Jay was guilty or if some third party played a role in Hae’s death, but I think most of us thought we’d find something concrete. Instead, the only new insight is how much we really don’t know about the murder of Hae Min Lee.

This frustrating lack of progress is to be expected. Unless you have zero knowledge of the criminal justice system (in which case, how the hell have you absorbed nothing from 12 hours of Serial?), you knew Adnan wouldn’t suddenly be freed from jail, and Jay nor anyone else would be suddenly cuffed in the nick of time for this finale. Yet, in our heart of hearts, we wanted some drip of a new, real development that affected these people outside the podcast narrative.

When I spoke to coworkers and friends today about the final episode, they were, unsurprisingly, disappointed. They weren’t necessarily disappointed by Koenig, but by the whole process. Koenig revealed new information from the University of Virginia Innocence Project, which had taken on Adnan’s case after she discussed it with the program’s director, Deirdre Enright. It turns out, the law students discovered that a serial killer, Ronald Lee Moore, strangled an Asian woman nine months after Hae died, and Moore was released from jail into the Baltimore-area less than two weeks before Hae’s death.

The team has a motion in the works to test DNA from Hae that the police curiously had never performed 15 years ago to see if there’s anything that matches Moore or anyone else. I found this as exciting as Enright did—she sounded giddy—but one of my coworkers was less enthused. He was frustrated that the motion hadn’t even technically been filed yet. Come on! Don’t you have some cards up your sleeve, Koenig? She can’t leave us this way, but she does. This ending is slightly excruciating, but wholly genuine and true to the ambiguities and hard questions the series has tackled from the get-go, which is why this untied ending is the right way to close the series.

So yes, in terms of new information pertinent to Adnan’s case, that’s all she wrote, or all she’s written so far. Koenig can capture a nation, but she can’t expedite the machinations of our criminal justice systems. Fans of the series will wait with baited breath at least until January when Adnan has an appeal hearing for post-conviction relief.

But even if that appeal goes in Adnan’s favor and he becomes a free man, we still won’t know whether he was really innocent or what happened to Hae Min Lee. The strongest most powerful takeaway of Serial may be its demonstration of how “not guilty” in court is very different from innocent in real life.

When it comes to this key discrepancy, Koenig doesn’t leave us hanging. “As a juror, I vote to acquit Adnan Sayed. I have to acquit. Even if in my heart of hearts I think Adnan killed Hae, I have to acquit,” Koenig tells us. This is its own moment of closure, before she adds, “But I’m not a juror.”

Koenig proceeds to deliver her deeply conflicted, sorta-kinda support for Adnan. “If you asked me to swear that Adnan Sayed is innocent, I couldn’t do it,” she admits. “Most of the time, I think he didn’t do it for big reasons, like the utter lack of evidence, but also small reasons, moments when he cried on the phone and tried to stifle it so I wouldn’t hear.”

Not only does she highlight how meaningless a court ruling is from a pure story-telling, thirst-for-the-truth perspective, but she answers what we as listeners have been wondering. Koenig must know by now that second to knowing if Adnan is innocent, we want to know if she thinks Adnan is innocent. Koenig has not been a sterile, objective narrator; she has openly voiced her biases, concerns, and gut feelings all along. What would have been a disappointing and disingenuous ending is for her to suddenly back-off and not tell us what she thinks after she has laid out all her information.

Koenig apologies for what she seems to treat as a sign of weakness. “I nurse doubt. I don’t like that I do, but I do,” she says. But for me, this admittance of uncertainty and doubts grounds Serial in reality. Koenig couldn’t end the series by giving us a happy ending or wrapping u the loose ends in a pretty bow, but she gave it integrity. Perhaps, that’s a solid second to the impossibility of knowing the truth.