1. Keep the ship moving forward.

ALEC: The writers work ungodly hours. Especially as we get into the second half of the year, they’re tired and stressed out. But they don’t sit there and say, “We got six episodes in the can. Fuck it, let’s just coast.” They push themselves. They are the smartest people I’ve ever met and what they write is very black diamond ski course.

ROBERT: As the season grinds on and we’re working 80-, 90-hour weeks our brains begin to atrophy. We’ll be in the writer’s room until early morning trying to keep the ball in the air. We need a joke! We need an idea! You pitch your idea to the room. And you know when it doesn’t work. There’s no more visceral reaction than people not laughing. But when you say something that totally bombs you hope someone else says, “Oh what I thought you were going to say was X,” or “What if it went there?” When you’re writing it’s as if you’re turning something over in your hands and making sure you’re looking at every side of it. Is it a piece of coal? Or a lump of shit? But it could be a diamond! What’s amazing about the creative process is how at each step you see so much that you hadn’t before. It’s always a little scary when you’re pitching it to Tina or Alec, but a good kind of scary. It’s important to create the environment where everyone wants to contribute so that moment of inspiration can happen because sometimes you’re just one step away. And there’s nothing more thrilling than when it works.

2. It takes all kinds.

ROBERT: There are different kinds of funny, so you want writers who share a comic language—they get your dumb bits and you get theirs. But you also want writers with a diverse range of experiences, so you get that sudden surprise of “Oh! That’s something I wouldn’t have thought of.” Currently our mix includes a former standup from Ohio who started writing later in life when he came out of the closet; an Illinois girl by way of Vegas and Amsterdam; the usual, unavoidable contingent of Harvard wangs (you have to hire them, they’re really good, but you need to surround them with people who don’t care at all that they went to Harvard and make them feel stupid all the time or else they become a monolith); a woman whose father is a Green Beret; a first-generation Indian who is supposed to be a doctor; a singer-songwriter who had a musical produced in L.A. and Korea; two white Protestants; a first-generation Persian woman; a comic-book-nerd writing team who couldn’t make eye contact in their first meeting with me and Tina; an Oxford M. Phil [master of philosophy] and a genius San Fernando Valley dirtbag burnout made good who used to work drunk on a missile-making assembly line. Put all these people in the same room and they not only speak the exact same kind of comedy language but they can laugh at things that the other guy says even though it has no relation to their own frame of reference.

3. Every joke has to count.

ROBERT: TV is a medium of limitations. We tell a lot of jokes, but we don’t have a lot of time to mess around. Every joke has to accomplish something, whether it’s smoothing over a transition, telling us something new about a character we’ve known for six years, or progressing the story.

ALEC: We have a lot of great writers. And in only 21 minutes the scripts are very, very nougat-y. I don’t want to just call them jokes—they’re full of cultural references. The names we drop! And how we drop them. Do you know how good it feels to say, “I can’t wait to see you tonight. What are you wearing? Really? You’re kidding. Condi! Condi! You’re breaking up!” We have a basic understanding that unless there’s something so glaringly wrong that you think, “I wouldn’t say that,” we do everything as written.

4. Write it real.

ALEC: In the world of sketch comedy, say on SNL, you can say the most horrible and offensive things and get a laugh, because when the three-minute sketch is over, that world no longer exists and the characters will never see each other again. Whereas, with 30 Rock, we can say things to each other on the edge of being offensive, but you can’t cross that line because those characters have to continue to live with each other for years.

ROBERT: We have what we call a unified field theory. We try to create a consistent universe in which we ask people to believe. In one of our first episodes, when we were still finding what the show wanted to be, we had written a joke where Jack said, “Did you see the factory explosion on the news? Don’t worry about it.” The suggestion was that Jack had caused it. Our producer Lorne Michaels said he felt that crossed the line. I thought, We need a joke there. We’re just trying to keep this thing moving forward. But Lorne was right. Jack does a lot of things that go right up to the line but even in our 30 Rock world, he doesn’t blow up factories.

5. Swing big.

ALEC: When the writers have written something crazy—either acting-wise, where I play Tracy and his whole family, or some complicated technical production, like split-screen or me talking to me, I’ll say to Robert, “Are you sure about that? How are we going to shoot it?” And he’ll say, “It’s a big swing.”

ROBERT: I’ll always have to ask myself, “Is it worth wasting the crew and the actor’s time?” Because if it’s not worth it, everybody will be wondering, “Why are we here at 11 o’clock?”

ALEC: But it usually works out.

6. Every character has to have their own voice.

ALEC: On a lot of TV shows there’s no distinction between characters’ voices. They all talk in exactly the same meter. It’s beat ... beat ... beat ... joke. Beat ... beat ... beat ... joke. Some of those shows are so successful and we wouldn’t mind having a bit of the crumbs from their ratings—but on 30 Rock every character speaks in their own voice. Tracy has his malapropisms. With Jenna it’s a hall of mirrors of self-absorption. Jack’s voice is his unerring, hopeless corporate drive. Kenneth’s is his suffocating decency and Liz’s is her self-defeating level of awareness.

7. Someone has to give.

ALEC: On 30 Rock every character is not only completely out for themselves, but they’re trying to sell everybody else on why they are right. But one person usually has to back down and say, “Okay. I’m not going to think only of myself. I’ll sublimate my feelings.”

ROBERT: If everyone is the voice of reason saying, “No, you can’t do that,” the narrative comes to a screeching halt. In the first season when we were working out all the dynamics, Kenneth [the NBC page] was one of the most helpful characters. He greased the wheels of the story because he was this lovable person who just for his pure love of television and famous people would always embrace the other person’s point of view. If Tracy wanted something crazy, like a fighting fish from Chinatown, Kenneth was the guy who would go out and get it. If Jack wanted something, a human mannequin, Kenneth would get it. And that allowed us to break through on a lot of story lines.

8. Mark your words.

ALEC: The writing is so smart and well crafted that articulation is critical. We have to really nail it. By the fourth episode, I realized that since the show is only 21 minutes long, the quicker we read the lines the better. And then you have to find all the rhythms to get the juice out of it. I might choose a word to pop for emphasis. And then decide where to take a pause and why. Bada-boom bada-boom bada-boom. Stop. Emphasis. Feeling. Today I had a line, “Do you know the history of this building, Stewart? During World War II, the Bazooka Joe Corporation took a softer version of their gum and made armor-plated bullets ... [deep breath] ... right here.” Where the line said, “Right here” I took a pause—as if to savor the line and say, “Can you feel it ... right here? The ground we’re standing on?”

ROBERT: A lot of actors feel like they need to let you know that they know what they’re saying is funny. If you do that it breaks the story. The great thing about writing for the actors on our show is that they play it real. The testament to Alec’s skills is that he can do an outrageous character like Jack’s doppelganger, the gay Spanish soap opera star Generalissimo. And he plays it so real that you’re right there in that reality.

9. Question the script.

ROBERT: As we develop a storyline I always ask, what new information have we learned in this scene? How is the story moving forward? How are the stories talking to each other? How is this building? How is the end better than the beginning? Is the end even in the beginning? And, most important, am I feeling bored reading this right now? If those questions don’t have satisfactory answers, then, however good the jokes are or acting is, you are failing in your duty to create something funny. It might be because of self-indulgence, incompetence, disregard for your characters, audience, or story structure or any number of other possible problems. But the most important question is not “Is this funny?” but “Are we failing at being funny in a larger sense?” And if we are failing, the solutions have to come from the same place the problems started—the writers’ room.

10. Be so good they can’t cancel you.

ALEC: Are there shows that outperform us earnings-wise in a 30-minute half hour? Of course. But does NBC make money off of us? Of course they do. A programming person might come in and say, “I want to take this show that’s making $50 million a year off the air because I can come up with an idea for a show that will make $70 or $80 million.” That’s what network programming is all about. But there is an intangible that I think helps us. There are monumentally successful shows that nobody in the business ever watches. Never. But we’re one of those shows that’s a little more interesting, funny and weird, like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad, that people in the business actually watch. When Lorne Michaels goes to the Grill in Beverly Hills or to Michael’s in Manhattan, people turn to him and say, “My son broke his leg skiing. He was in bed and we watched all of Season 3 together.” Maybe it’s my fantasy, but I believe that one of the things that has kept us on the air for six years and maybe beyond is that when these network execs walk into a room everybody there—and their kids—watches our show.

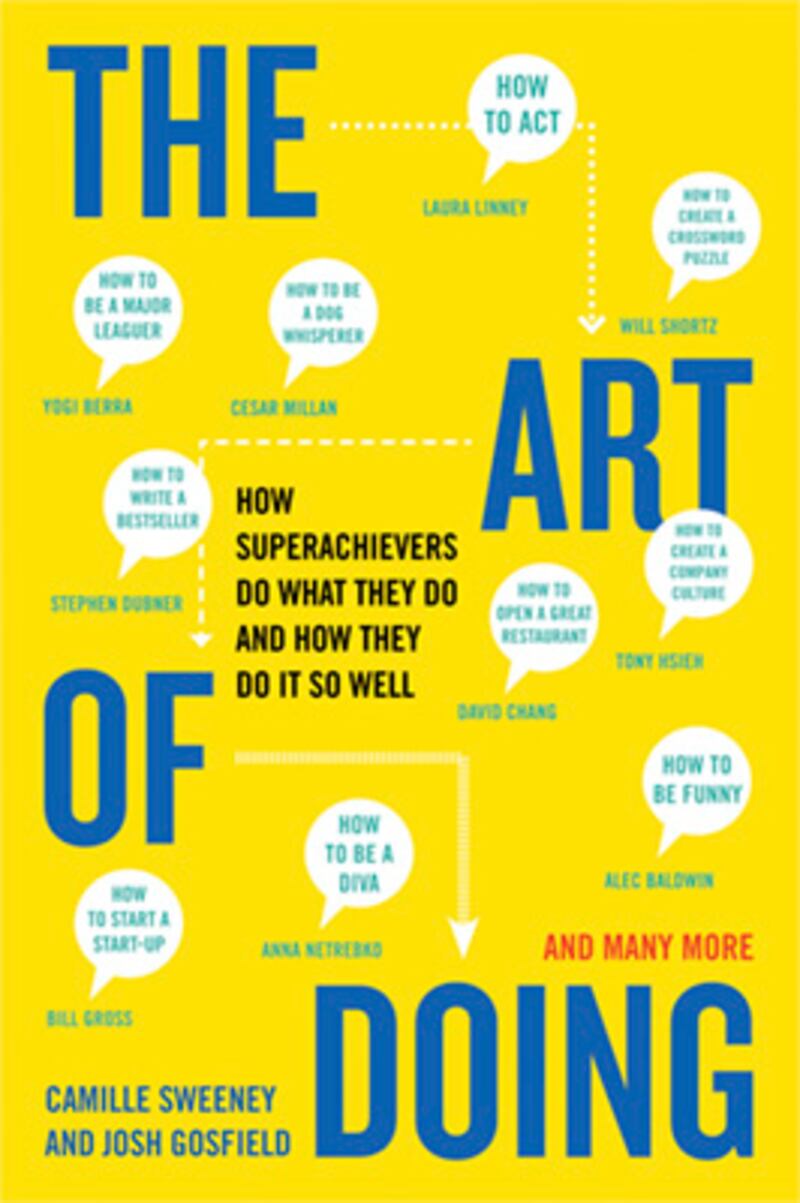

This article has been adapted by arrangement with Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from The Art of Doing: How Superachievers Do What They Do and How They Do It So Well by Camille Sweeney and Josh Gosfield. Copyright 2013 by Camille Sweeney and Josh Gosfield.