There has rarely been a more truthful 90 minutes on the subject of manipulation and opportunism within the sometimes lunatic cubicle of race than HBO’s new documentary Thrilla in Manila. ( Click here for showtimes.) This one is so special because it pulls the covers off of a ritual unique to our history: For at least the last 40 years, we have been duped whenever possible by ruthlessly narcissistic black men. Their game has been using politics and race for no real purpose other than self-elevation and big profit.

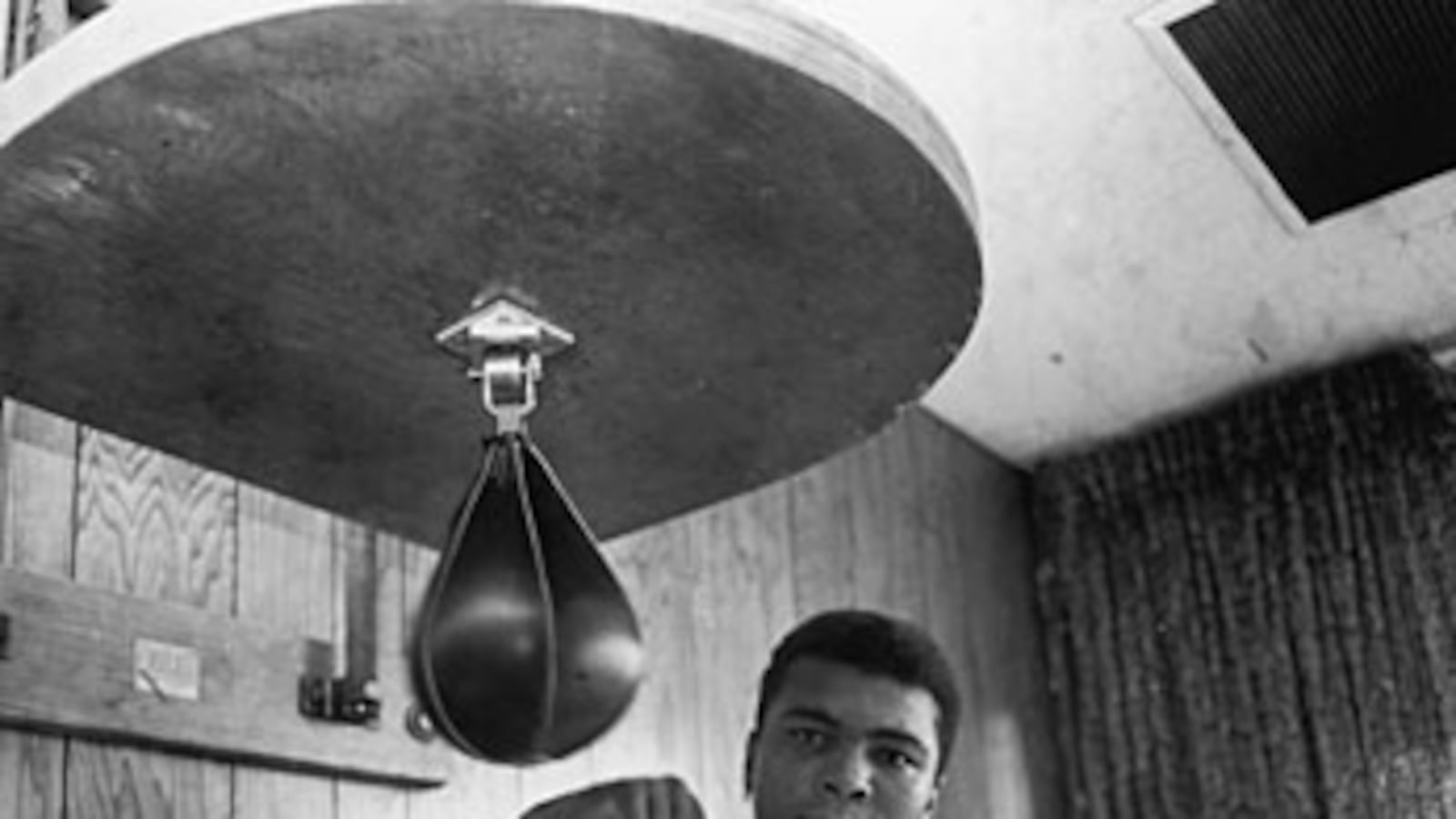

This documentary takes the shine off of Muhammad Ali and is very nearly great primarily because it does something extremely difficult. We see with fresh clarity the extent to which Ali exploited the turmoil of the civil-rights era with great dishonesty. But the movie does not deny the man the genius of his glowing skills and the singularity of his astonishing feats. Thrilla in Manila only clarifies what he actually was during his period of greatest fame and influence.

The accepted myth is that Ali represents both extraordinary athletic abilities and a brand new level of courage and integrity because he took great career risks and stood up to white America in a way that separated the former champion from all of the black athletes who had come before him. He had testicles too big for white men to cut off and that is why they attempted to destroy his career when he refused to serve in the Army on religious and racial grounds.

He claimed that his religion, Islam, was opposed to war. (Yes, it did take big balls to say that and hold a straight face). Ali went further and made another much more inflammatory point: As a black man living in an obviously racist country, the very thought of invading a non-white country was despicable: “The Viet Cong never called me a nigger.”

That entire stance was a Dagwood sandwich of bunk. Seeing witnesses from within the Ali camp and the Nation of Islam itself, we learn that the boxer was repeating ideas that were not his at all and only doing exactly what he was told. The documentary could have been much, much stronger had it focused more fully on the absurd racism taught by the Nation of Islam and for which Ali became an obnoxious mouthpiece after being led into the fold by Malcolm X.

It was a serious mistake for Thrilla in Manila not to even mention Ali’s relationship to Malcolm X, the man who introduced him to the mix of cartoon religion, racism, and separatist politics—and whom Ali rejected as soon as Malcolm X fell out with the Nation and charged its founder, Elijah Muhammad, with being a fake, a liar, and a hypocrite who had fathered illegitimate children by his young secretaries. Hot stuff. Ali’s turnabout is seen as a revealing betrayal and a foreshadowing of betrayals to come.

While Thrilla does not look into that, it is still a far more than merely good move toward a fresh and unsentimental awareness of the multilayered hustles run by one of our most famous men.

Many assumed then and still believe—on the quiet!—that Malcolm X’s attacks on Elijah Muhammad were what actually formed the motives for his assassination. In the 1995 documentary about that assassination, Brother Minister, Louis Farrakhan deepens the assumption of culpability. In a secretly filmed Savior’s Day Chicago address from 1993, one of our most prominent demagogues virtually admits that the Nation “dealt” with Malcolm the way any nation would deal with a traitor whom it had raised from nothing and taught all that he knew.

For all of the claims that Ali had the courage to stand up to the white devils, he seemed not to be so courageous when facing black thugs. It is also thought that the Nation of Islam was able to hold the fighter as a virtual prisoner while pretending to provide him with protection simply because the champ was terrified of them. He felt that if a man as famous as Malcolm X could be mercilessly taken down for talking against the cult and its leader, an illiterate boxer with little besides surpassing ring skills and a gift of gab would have absolutely no chance at all.

What will disappoint those who believe most in the champion’s sterling integrity is the way that Ali betrayed his three-time opponent Joe Frazier. That was part of a ruthless and self-serving libel against a man who had helped him financially when he was broke and had campaigned to get Ali his license to fight after he had been barred from the sport by the boxing commission.

Oh, they were fast friends when Ali was so far down that everything else looked up. But his whole demeanor changed when the Supreme Court—those white devils in black robes—ruled that the boxer had been unfairly deprived of his license to fight. (Since ruling against public-school segregation in1954, those particular white devils seemed to have periodically forgotten that they were part of a demonic race, according to Elijah Muhammad.)

Liberated by the highest court’s decision, Ali viciously railed against Frazier as an Uncle Tom and a servant of the white people—“the enemy.” This was partially intended to create a racial melodrama in which Ali, the clearly handsome, light-skinned, and charismatic man was seen as the hero, while Frazier, the dark-skinned, flat-nosed Negro from the Deep South, was defined as a boot-licking lackey whose mind had been screwed up by the white people busy at work using him against the black-freedom cause.

Friendship and loyalty were things that meant much to Frazier and we are shown that he has never recovered from the wounds his former buddy gave him as well as the effects on his children by all of the black millions who went for Ali’s game.

Doubtless, Ali was a man who did not care whom he hurt or betrayed and did not hesitate to say or pretend to believe something if it would help draw more media attention and create more zeros on his paychecks, which went from thousands to millions during his career. That level of pay was so rare 40 years ago that there was little Ali would not do to rake in as much as he could from the moment that he discovered just how much the word much could mean.

The boxer had begun his career as a brash loudmouth who modeled himself on white braggarts in the wrestling world, Gorgeous George in particular. This brought disdain but a lot of attention as Ali went on to win the heavyweight championship. The position as the bad boy of sports was intensified when he followed Malcolm X into the Nation of Islam, changed his “slave name” from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, and soon became a full-fledged race hustler.

The severely racist America in which men like Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Jackie Robinson grew up and spoke the lingua franca of the trained body in competition would not—for a second!—have put up with the Nation of Islam and Malcolm X or Muhammad Ali and the “revolutionary” saber-ratting of the Black Panthers. But the race hustlers and ethnic dupes arrived in force when America became so deeply conflicted that a crisis of national identity was afoot.

Many different ways of defining the true meaning of this nation arrived in the wake of Senator Joe McCarthy’s jive time in power. Conservatives have yet to figure out or admit to just how much damage that toxic patriotism did to this country. We should all know by now that we have spent more than 50 years trying to heal the wounds imposed by all of those loud, finger-wagging committees that were our homemade version of the fake trials used by Stalin in the 1930s.

The Manchurian Candidate was right when imagining that our most extreme right wing could surely have been a Communist plot to destroy the country. And the accidental Manchurian Candidate of the civil-rights era may well have been Muhammad Ali because of the way he manipulated Americans through their understandable disillusionment, disappointment, and their disgust at the way things were and had been for far too long. Like all race hustlers, the fighter harped on things that were half-truths but a partial truth is never a complete lie.

For all of its chest-thumping claims about freedom and equality, America had allowed segregation to be unconstitutionally established in our South not long after the Civil War. The shooting war had been lost, but there was a victory in the policy war and redneck terrorism held that victory in place. Those dark and bloody truths about American life provided race hustlers with plenty of fertilizer to help grow their crops of thorns before taking them to market.

Though far from a subtle man, Ali understood this and, at the height of his career, one thing remained constant: The champ was never above a willingness to demean, humiliate, and make his opponent a scapegoat for the nation’s adolescent sense of simplistic racial categories and ideas about ethnic loyalty.

Those who had no angle on any of this were given a very simple-minded one by Ali, who was never given to substance beyond crude but cute doggerel. According to the boxer, there were only two ways to look at Negroes and for Negroes to look at themselves, either as a militant freedom fighter or an Uncle Tom. As Ali explained it, the individual Negro was proud of his African heritage and at war with the color order of America, or was just a dumb chump who had been misled into loving and following white people.

The example of the political traitor was appropriated and brought into the world of race. This traitor to his race was the victim of brainwashing but did not hate his enemies, he hated himself—his skin tone, his hair quality, his facial features, and his physiognomy. He was a dead monkey. He had to be awakened to the light of self-love and strong thinking freed from the influence of white folks. The Negro needed strong medicine of the sort that came from within the Nation of Islam.

The political rock and roll observed in the grimly surreal postures of the Nation of Islam, the black-power movement, and the Black Panthers were made more important than they actually were by a media always looking for fresh black foolishness it could pretend should be taken seriously.

In that context, Ali talked a lot of repulsive stuff and was a race hustler of just about the worst sort, but there is another truth as easily proven. Only he could have given us those truly great fights, such as his monumental victory over George Foreman in Zaire and his indispensable part in the final epic battle with Joe Frazier. Former light heavyweight champion Jose Torres described that brutal Manila ballet in conversation as “beyond boxing.”

Beyond boxing is the inarguable proof that life itself always has, somewhere, the resources to prevail over what we believe is impossible. We are simultaneously horrified and enlarged by the last section of Thrilla in Manila as it sums up what those two titans embody. Flesh and bone subsume human morale, courage, and will. Those two men rode the bull of the impossible as they endured such formidable punishment from each other for 14 three-minute rounds in the airless ring where the temperature was 125 degrees. Using perfectly disciplined violence, they produced what is surely the greatest heavyweight fight of all time, which means that it is also one of the greatest human events of all time.

Whatever masculinity is and whatever makes it so magnetic beyond sex or hype or sentimentality or the fluff and mud of politics, is forever on display in that mutually and permanently damaging contest. It is something similar to witnessing child birth at the point when human flesh, muscle, and elasticity move beyond physical pain and approach the level of religious enlightenment. Only the very greatest in the world of sports ever get there, but they beckon to the rest of us and reaffirm the three words that Barack Obama made into a mantra for our moment and all that have preceded and will follow it: Yes, we can.

Stanley Crouch's culture pieces have appeared in Harper's, The New York Times, Vogue, Downbeat, The New Yorker, and more. He has served as artistic consultant for jazz programming at Lincoln Center since 1987, and is a founder Jazz at Lincoln Center. In June 2006 his first major collection of jazz criticism, Considering Genius: Jazz Writings, was published. He is presently completing a book about the Barack Obama presidential campaign.