By now, the story is familiar. On November 2, 2007, Meredith Kercher, a 20-year-old British student, was found dead in a house in the Italian city of Perugia, her throat slit and her semi-naked body wrapped in a duvet. In the days that followed, Kercher’s roommate, Amanda Knox, a 20-year-old American college student in the midst of a semester abroad, and her then-boyfriend, a 23-year-old Italian student named Raffaele Sollecito, became the prime suspects, along with an Ivorian man, Rudy Guede, whose DNA was found in Kercher’s vagina.

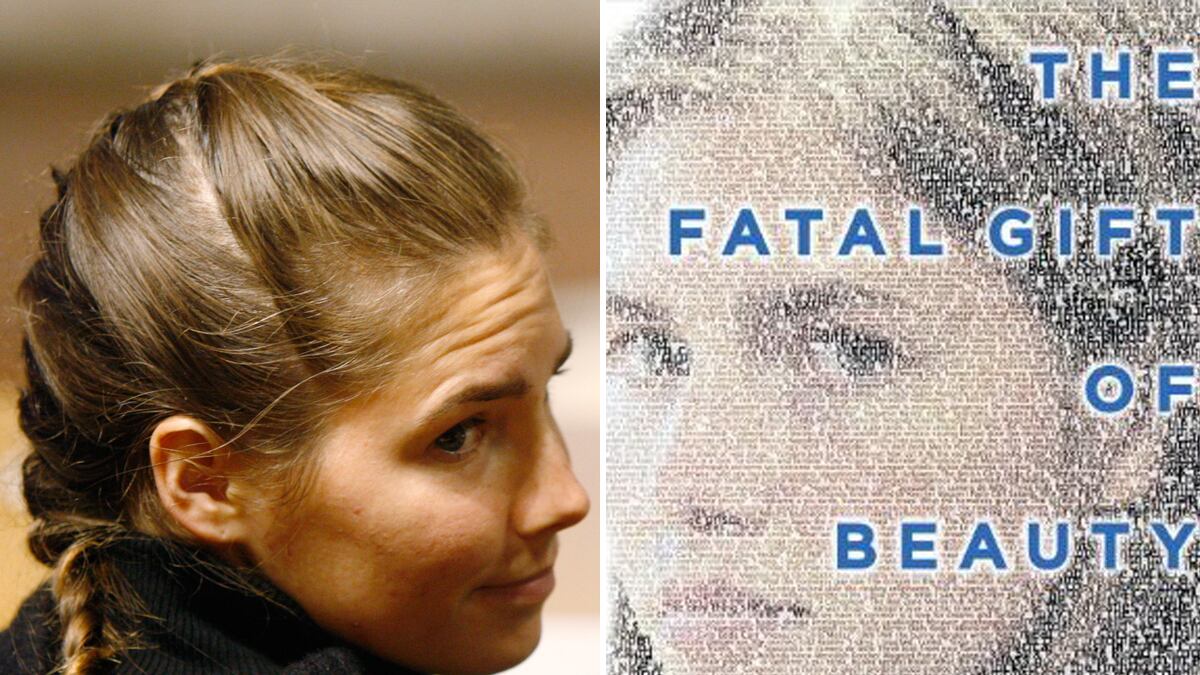

When the trial began in 2009, the prosecution put forth a theory that the three suspects had participated in a twisted sex game gone awry. The story was eventually—in one way or another—accepted by the jury, and Guede was sentence to 30 years in prison (his sentence has since been reduced); Knox and Sollecito were sentenced to 26 and 25 years, respectively. In the years since the investigation of Kercher’s murder began, there have been countless articles, numerous websites devoted to the victim and the accused, several books, and a Lifetime movie. A new book, Nina Burleigh’s The Fatal Gift of Beauty: The Trials of Amanda Knox, is a well-written and exhaustive addition to the growing genre.

Why, among all the horrible things that happen every day, has this particular case captivated such a large audience? For me, its eerie familiarities with my own life created part of the pull. When the story broke, I was an American student studying in England and could not help but feel (gruesome details aside) a certain degree of fleeting kinship with Knox. I had friends who, like Knox, had taken rooms in out-of-the-way student houses, hoping to move beyond clingy American expat circles. I knew foreign students who, like Knox, had begun relationships with locals, aware that foreigner-appeal played a part in their attraction. (The parallels pretty much stop there.)

Now, reading The Fatal Gift of Beauty, I’ve come to think that the overlap between Knox’s experience and my own stems not from actual similarities but from a broader preoccupation; Knox’s story, in many ways, is that of an American ingénue in Europe—Henry James’ Daisy Miller, the “eternally green” protagonist of the bestselling 1950s novel The Dud Avocado, or Sex and the City's Carrie Bradshaw in Paris—a fresh-faced American girl, blithely fumbling through the staid ways of the Old World. Knox herself knew this to a certain extent: “How young women experience the world and how the world experiences young women … It’s an age-old question, isn’t it?” she wrote to Burleigh just 13 days after her conviction. She was self-aware, even, of the role her prettiness played in earning her admirers. “If I were ugly,” she wondered, in her prison diary, “would they be writing to me, wishing me encouragement”?

Burleigh’s book asks a similar question: Was Knox a naïve American, indicted for a crime she had little to do with and made to navigate a foreign legal system without much help? Knox’s childhood—divorced parents, but a generally happy family, good grades, soccer—was banal rather than sinister. A chapter titled “American Girl," beginning with a quote from Tom Petty—“Well she was an American girl/ Raised on promises/ She couldn’t help thinkin’/ That there was a little more to life somewhere else”—further depicts Knox as an adventurous American ingénue. Predatory, drug-filled Perugia stands in contrast; a nightclub, for example, is filled with sleazy Don Juans and docile Daisys: “the Italian boys, emboldened by the growing disorientation of the English-speaking girls … rub up against girls in the dark, grinding against them ... Stunned, flattered, and titillated, there is nothing to do but submit.” Burleigh doesn’t completely shy away from an alternate interpretation, pointing out that the prosecutors of the case perceived Knox as an amalgam of wilier feminine flaws: “beautiful, sexual, manipulative, narcissistic to the point of fame-loving, and jealous to the point of murder”? But Burleigh’s instincts seem to lie elsewhere.

Ultimately, however, the deep and lingering fascination with this story lies less in contemplations of American innocence than specific horrors: the slashed throat, the splayed body—naked from the waist down—the bloody footprint found on the bathroom mat. And, in the relation of such detail, Burleigh is excellent, reporting with vibrant but sober diligence that also extends to less morbid matters: the history of Perugia, including the town-gown conflicts between the foreign-heavy student population and well-to-do Perugians; a legal system that allowed Knox and Sollecito to be detained for a year before being charged; the tumultuous childhood of Guede, born in Ivory Coast, brought to Perugia by his father, and later adopted by one of the richest families in Perugia. Burleigh is also thorough on matters of interpretation: The half-covered body, Burleigh writes, was “a sign, the prosecutor felt, of feminine pietà—sympathy. Later, Italian criminologists would bolster this notion and say publicly that killers who cover their victims with blankets are usually female. American criminologists say that gender has nothing to do with it.” Only occasionally does her investigation take her too far, eliciting some extremely banal statements: “Shutters are an important aspect of Italian life.”

This book should be read for its detail and analysis. It will probably by read with a more general and direct objective—to find out what, exactly, happened. This is a timely question. In June, in an early phase of Knox’s ongoing appeal, a court-appointed panel of experts deemed crucial pieces of the forensic evidence used to convict Knox and Sollecito inconclusive. During the trial, prosecutors had claimed that the alleged murder weapon—a knife found in Sollecito’s apartment—carried traces of Knox’s DNA on the handle and Kercher’s on the blade, and that a detached bra clasp belonging to Kercher carried traces of Sollecito’s DNA. Recently, experts concluded that investigators may have contaminated the evidence when they collected it.

Fatal Gift, for its part, stresses media misinterpretations and offers explanations for apparently damning evidence. To explain Knox’s fingering of a local nightclub owner as Kercher’s killer and another statement (issued by Knox) that put her at the house when the murder took place, Burleigh points out that her translators were a “subjective sieve” through which her words were filtered. She also summons exculpatory evidence whenever possible: “Police found Amanda Knox’s prints in one place only, on a water glass in the kitchen.” In her assessment of Knox and Sollecito’s past, Burleigh finds nothing that “indicated a predisposition to aggression, let alone murder.” In her final chapter Burleigh plausibly conjures an alternate murderer.

Burleigh’s book might shift public opinion. It did mine. However well researched and written, it seems unlikely it will affect the fate of Knox’s appeal or accelerate the process. And so, for the time being, Amanda Knox remains in prison, exposed to a very different slice of life than the one she anticipated when this appealing and eager American girl set out for her European adventure.