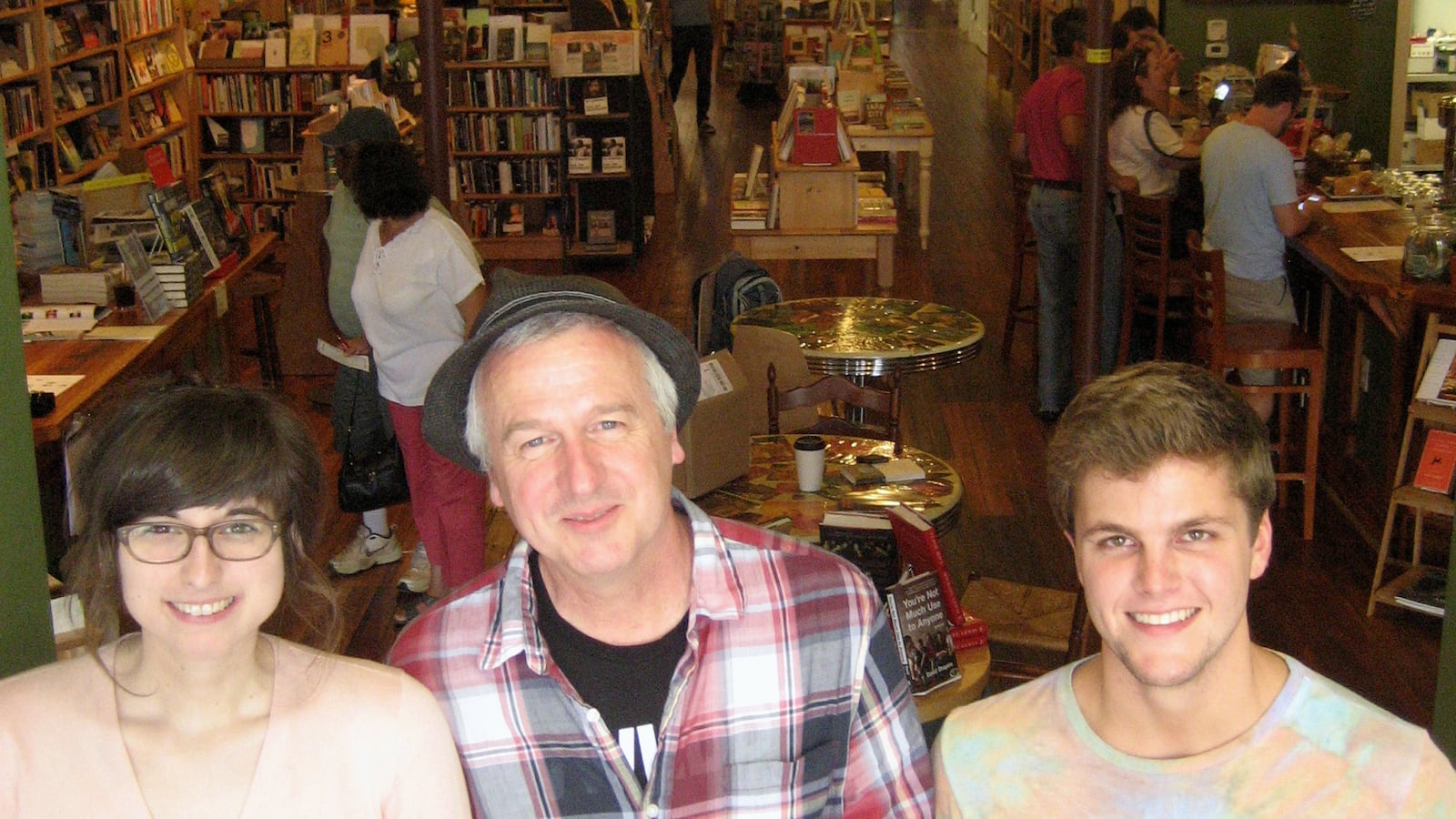

Things had come full circle. Back in 1996, I sold my second novel, quit my job as a newspaper reporter in Greensboro, NC, and got to work on novel number three. Now, 18 long years later, Motor City Burning had finally been published and I was standing in a packed bookstore about a mile from the apartment where I’d started writing the book. I was reading from its pages and spinning some of the songs that wind through the narrative, by John Lee Hooker, Tammy Wynette, and the Temptations.

The store, Scuppernong Books, didn’t exist when I started writing my novel. It was co-founded last year by Brian Lampkin, a 53-year-old poet from Buffalo, NY, who surveyed Greensboro’s newly vibrant downtown and sensed an opportunity. When he discovered a vacant space on the main drag, he decided to open an independent bookstore with a professor at the local campus of the University of North Carolina. A year and a half later, the owners have added another partner, Kira Larson, and the place is buzzing with life, a magnet not only for book buyers, but also for meditation sessions, children’s story hours, talent shows, young writers’ groups, and readings by everyone from seasoned novelists to poets to homeless people.

“For me and the six people who work here,” Lampkin says, “it was something that was missing from our lives—a place where ideas and conversation matter. When you walk in the door you feel like you’re among human beings. The gratitude we got from the community was shocking. We’re not going to get rich, but we’re paying people well and giving them a sweet life. It’s great for downtown. Independent bookstores are intellectual centers of a city.”

Indeed, the crowd at my reading was attentive, inquisitive—and willing to spend money on printed books. This intimate contact is vital to both readers and writers—and it’s something that can’t be replicated online. For readers, it’s a chance to get inside the process of how books get made. For writers, who spend years in solitude putting words on a page, it’s an invaluable chance to connect with their audience.

Which brings us to the elephant in the room—the rapacious advance of online bookselling, personified by Amazon. Like most independent booksellers, Lampkin is no fan.

“I would like to say there’s room in the world for everyone—if Amazon felt that way,” he says. “When I worked at a bookstore in Seattle, the company was revered as part of the growing internet economy. But now I see them as the giant vampire squid, the enemy of the independent bookstore. I do have a sense that I must resist, but I can also see how they’re good for writers.”

Better for some writers than others. As I’m writing these words, Edan Lepucki, my colleague at the online literary magazine The Millions, has just landed at #3 on The New York Times bestseller list with her debut novel, California. The book was rescued from the anonymity reserved for most first novels by the TV host Stephen Colbert, who, like Lepucki, is published by the Hachette group. When Hachette refused to knuckle under to Amazon’s demands, the online retailer yanked all Hachette titles from its website, a crippling blow to Hachette writers. In retaliation, Colbert mounted a campaign to turn an obscure book into a bestseller. And it worked.

Colbert and Lampkin are not alone in their distaste for the online behemoth. The night after my reading at Scuppernong Books, I appeared at the venerable Regulator Bookshop in Durham, NC, which was co-founded by a Duke grad named Tom Campbell way back in 1976, before there was an internet, Amazon, e-books, or chain bookstores.

“What we’ve done to respond to all that is to still be people who are interested in books and can have a conversation,” Campbell says. “Books are intimate things, and we can provide something that Amazon can’t. People still like to walk into a physical place and pick up books and talk to people. It’s almost retro in today’s environment, like vinyl.”

Campbell describes the books on his shelves as a “curated” collection. “There’s a reason why every book is in this store,” he says. “It’s not just a business decision. Either we like it or we know a customer who might like it.”

Like Scuppernong Books, the Regulator has adapted to the Internet age, hosting events and trying to connect with readers through Facebook, Twitter, and a website. The shop also sells cards, tote bags, puppets, and notebooks, and there’s a room devoted to an eclectic selection of magazines. In a counter-intuitive twist, Campbell believes that the acceleration of life brought on by the Internet may actually be working to the advantage of independent bookstores.

“People don’t have as much time as they used to have,” he says. “They don’t read as many book reviews. We can guide people to books that we or someone in the business feels strongly about—and that helps. People need more guidance now.”

As he was saying those words, a customer in a nearby aisle said to her friend, “Amazing! Look at this! You can find things in this store that you can’t find anywhere else.”

Campbell smiled. “Did you hear that? That’s one of the things we’re all about.”