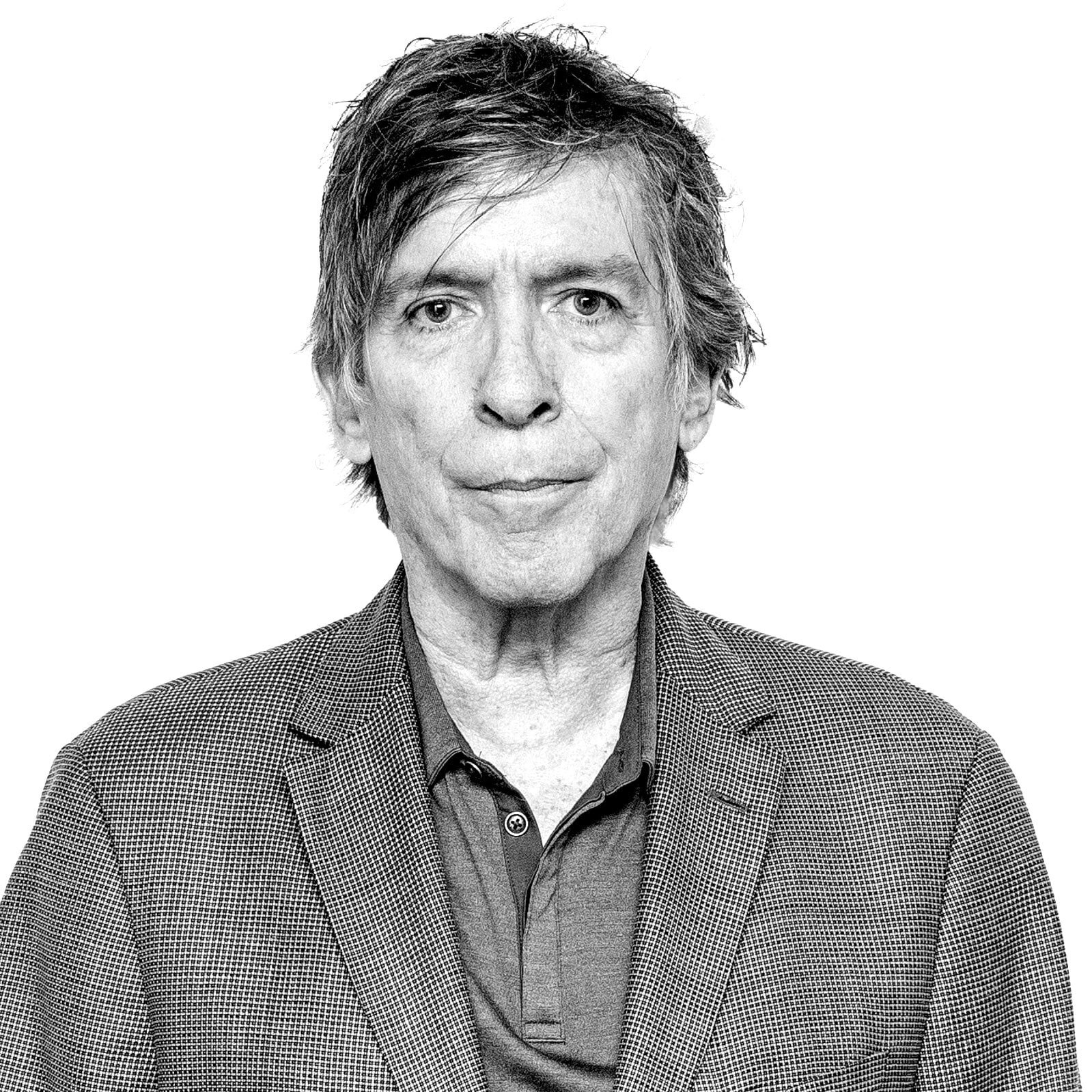

Lou Reed was a famously hostile interview. The first time I approached him in a journalistic capacity, somewhere back in the 1980s, the first words out of his mouth were, “No questions about drugs or fags.” This obviously closed off some important avenues of inquiry, but I guess we muddled through. He didn’t hit me, anyway.

I wish I could say I can’t believe he’s gone. But Lou was 71, and he barely missed checking out before he got an emergency liver transplant last spring. In any case, he has left behind a body of work—really great records, truly indelible songs—that won’t be fading away in any conceivable future.

The fact that the four albums Lou recorded with the Velvet Underground between 1967 and 1970 didn’t sell is one of the great music-biz bafflements. Heard today, they’re clearly thick with hits: “Femme Fatale,” “Venus in Furs,” “White Light/White Heat,” “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Sweet Jane,” and on and on. (The version of “White Light/White Heat” that he performed at the 2006 MTV Video Music Awards, backed by Jack White’s Raconteurs, could have been one of the great TV rock moments—if the group had been given more than 54 seconds to play it.) The low budgets with which the Velvets were mostly saddled ensured that their recordings weren’t disfigured by trendy production horrors like phasing or ping-pong stereo. And so they sound timeless. And perfect.

Lou gave the impression of having endured a lot of bullshit in his life, and being disinclined to endure any more—thus the aforementioned press hostility. There was his teenage electroshock therapy, for one thing (it failed to cure his bisexuality—go figure). And no doubt his—how to put it—unrewarding years on Verve Records with the Velvet Underground must have been an evergreen annoyance. (Frank Zappa, whose Mothers of Invention also were signed to Verve at the time, once told me the label would press more albums than its acts ever knew about, and the overrun “would go into the back of somebody’s car and be shipped across state lines and be traded for rooms full of furniture.”)

But as he got older, Lou mellowed a little. I would occasionally see him around the West Village, walking a very small dog, or in the Meatpacking District with his wife, Laurie Anderson, sitting at one of the outside tables at Pastis, smiling in the sunshine. He once introduced me to his t’ai chi master, whose praises he never ceased singing. And one night, at some murky function, I found it unusually easy to pry him out of a conversation with Julian Schnabel, the kilt-wearing art guy, in order to meet Ice-T, still a rapper then. They’d both been on Sire Records at one time but had never met, and Ice-T was keen to make Lou’s acquaintance. Lou seemed genuinely happy to oblige.

Indeed, Lou’s musical tastes were often surprising—he once told me, at some length, about his admiration for Neil Young’s marathon guitar-soloing. But he had an especially deep feeling for black music. You can hear his love for the doo wop of his youth in Velvets songs like “I Found a Reason” and “Candy Says.” “There She Goes Again” lifts the riff from Marvin Gaye’s 1962 hit “Hitch Hike,” and I once saw him cover Smokey Robinson & The Miracles’ “The Tears of a Clown” at a small-club fundraiser (“Yet another benefit,” he grumped). Just last summer he weighed in at The Talkhouse with an out-of-nowhere review of the new Kanye West album, Yeezus. (“There are moments of supreme beauty and greatness on this record,” Lou wrote, “and then some of it is the same old shit.”)

In 1993, my friend David Fricke and I somehow got invited to witness a reunited Velvet Underground—Lou back together with John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker—rehearsing for an equally out-of-nowhere European tour. I guess it was the last time they ever played together in this country (despite widespread hopes and rumors, the Euro outing never extended back to the States).

The band was assembled in a small Manhattan rehearsal space, the set list was all classics, and to watch Lou administering his trademark drawl to “Venus in Furs” while John Cale sawed away on his viola was like being present in heaven on an especially good night. It was like a private concert—an unimaginable thing. And unrepeatable.