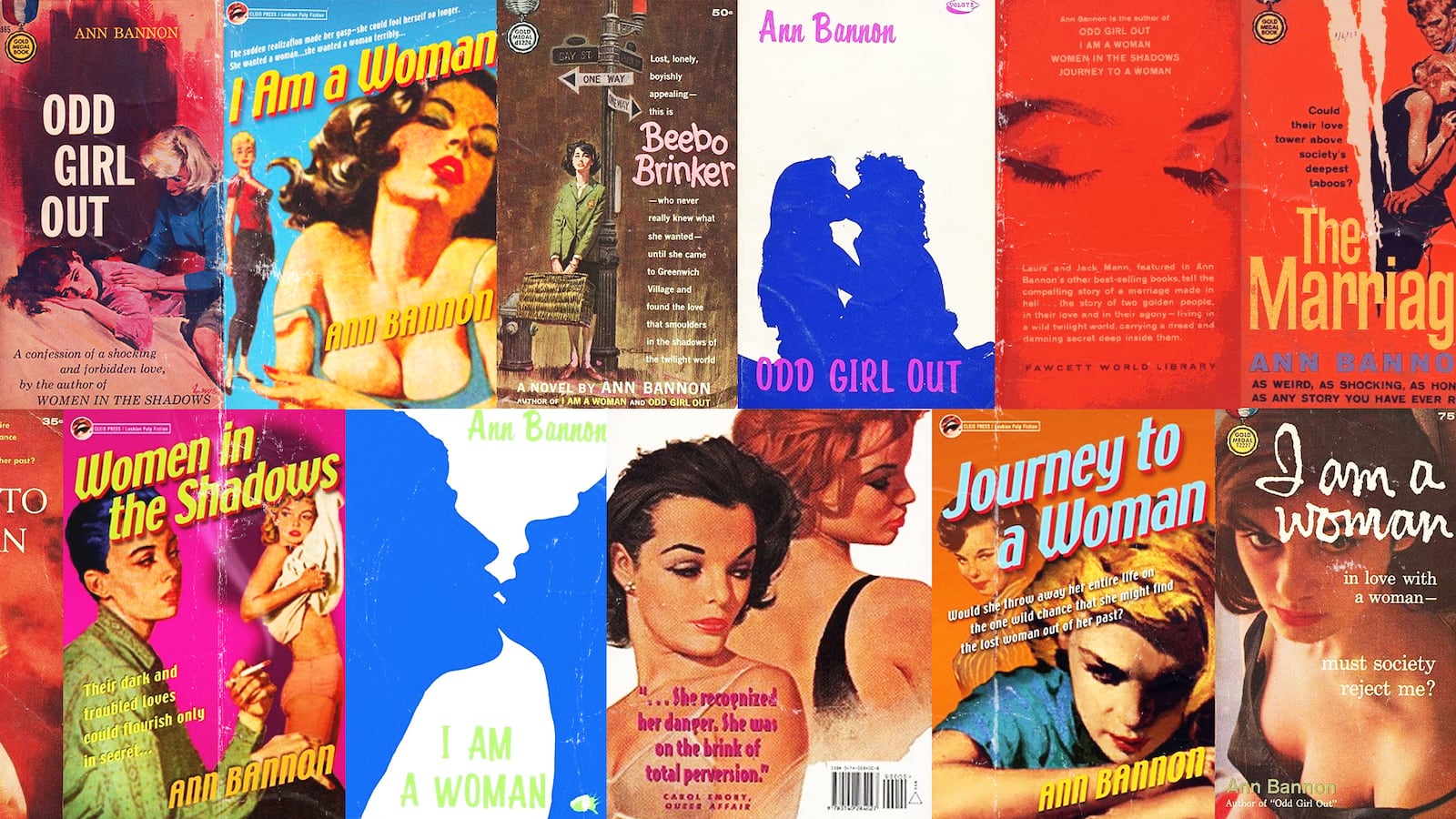

I have a date with the “Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction,” and I can’t wait to hear her swinging-from-the-chandeliers stories. The name “Ann Bannon” conjures up images of heaving breasts and scarlet lips on lurid-looking books with cover lines promising depravity, sleaze and a roll-around in the shadowy world of “strange passion,” the code word for lesbian activity back in the world of the 1950s pulp novels that made Bannon famous—or infamous.

However, when I arrive at the Palm Springs dinner party, thrown to celebrate the imminent opening in Palm Springs of The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (at the Desert Ensemble Theatre, Dec 17-19), a play by Kate Moira Ryan and Linda S. Chapman based on Bannon’s oeuvre, it’s a while before I even notice Ann Bannon.

Husband and husband Luc and Bud are showing me round their white marble home with its four Christmas trees while Bud tells me about working alongside Harvey Milk in San Francisco back in the day. (“I’m no stranger to having Molotov cocktails thrown in my face!”) Only afterwards do I notice a quiet, elegant woman in the corner of the lounge, politely accepting Luc’s offer of a Lemon Drop cocktail. “I’d better have a glass of water first,” she says with a shy smile.

Could this be the woman who wrote lines like, “They rolled over each other on the floor, pressing each other tight, almost as if they wanted to fuse their bodies… Her body heaved against Beebo’s in a lovely mad duet. She felt like a column of fire, all heat and light, impossibly sensual, impossibly sexual”?

It’s from 1959’s I Am a Woman (“In love with a woman—must society reject me?”) one of a series of five books published between 1957 and 1962 which became known as the Beebo Brinker Chronicles. I Am A Woman introduces Beebo herself, Bannon’s supreme creation and the sex scene occurs when confused femme Laura can’t resist the charisma and sex appeal of the young masculine woman any longer. Bannon is on record as saying that Beebo Brinker, who works as an elevator operator just so she is allowed to wear trousers, is “the butch of my dreams.”

When we start talking, she says, with a chuckle, “It would be nice to put something in the article to make me sound more adventurous than I was able to make myself back then!”

And so begins a fascinating date with this slender, pin-sharp, 89-year-old Illinois native so unlike most of the flamboyant, rebel-rousing feminists and lesbians I have interviewed over the years.

“A lifeline for women”

The lesbian literary landscape between 1928, when Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was published (with its famous “sex scene” : “…and that night, they were not divided”), and the 1970s when lesbian feminist publishing exploded is often viewed as a blank space. In fact, from 1950 until the mid-’60s it was a vibrantly colorful space, thanks to a revolution in the publishing industry.

In 1939 Pocket Books invented a way of selling massive quantities of books in America: print them on cheap paper, give them flashy covers and alluring cover lines and deliver them in bundles to drugstores, cigar stores, lunch counters, airports and railway stations as if they were magazines.

Until then, books had only been available in the scattering of book stores around the country. Peopled with gangsters, cowboys, detectives, drug-crazed Beatnik girls, sales grew tenfold as the books cost 25 cents, the same as a packet of cigarettes. Plus, in the days before TV, the risqué covers suggested that important and secret information lay inside. And actually, it did.

Although pulps were likened to the 19th-century Penny Dreadfuls, they became the launching pad for a raft of authors from Gore Vidal and Ray Bradbury to Mickey Spillane and Patricia Highsmith. And for lesbians, their lowbrow image worked in their favor. It meant that papers like The New York Times refused to review them and so they were off the radar of the repressive authorities.

Bannon sold 2 million copies with her first publisher, Gold Medal Books, which became a rival to Pocket Books. In a time when you were lucky to sell a few hundred copies of a book, Gold Medal Books had initial print runs of 300,000.

Ann Bannon was where you went to get information about being a lesbian in the days when you’d need special permission to access books in the library—which would tell you that you were going to hell anyway. The novels were a lifeline for women.

Today, as well as being taught in Women’s and LGBT Studies courses, she is mentioned in many memoirs. Kate Millet in her 1974 autobiography, Flying, admits to hoarding Bannon’s novels “because they were the only books “where one woman kissed another.” She actually burned her Bannon books before she left for a trip to Japan in case her sub-letter discovered them.

Lana Turner’s daughter Cheryl Crane, famous for murdering her mother’s violent boyfriend aged 14, reveals in her autobiography that she identified for many years with confused femme Laura, from Bannon’s first novel Odd Girl Out.

It turns out that during the short window in which Bannon wrote her five famous lesbian books (Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman, and Beebo Brinker) she was married to a man—and remained married to him for 27 years.

And she’s not even called Ann Bannon. Her real name is Ann Weldy and she used the nom de plume because she was extremely keen to remain in the shadows herself.

Weldy admits her childhood growing up in Illinois was “very conformist.” Her mother was “a great beauty. She went through her flapper stage and her crazy stage—which included having me.”

Her mother had fallen in love with a boy at Smith college, “a farm kid from Indiana.” He was driving her back to college one time when, “in a dreamy conversation,” he said that he wished they could be together more. “Whereupon she said, ‘I wish we could be married,’ and he slammed on the brakes and drove into a ditch!”

When they’d limped out of the car, he drove them immediately to the next town and they got married. “She didn’t know what she was getting into. Her father, my grandfather, was a successful surgeon and she’d grown up in the Chicago suburbs. But her parents were Victorian in outlook—they told her nothing about sex.”

Her parents consummated the marriage only one time and her mother got pregnant with Weldy, who didn’t know her father existed until she was 10. “He was sweet but dull,” but, Weldy underlines, “he did put me through college which was a huge thing in my life.”

The father she loved most was her mother's second husband, a “well-intentioned, feckless jazz piano player. He had no idea how to make money. I adored him.” But her “darling daddy,” died of strep throat when she was seven, “just before penicillin was invented.”

Her mother had had one son with this second husband and then she married again and had four more sons. The line of her three-times married mother was, says Weldy, “‘For a small town girl I’ve lived quite an unusual life.’ But she was her mother’s child. A proper lady. You couldn’t joke with her about it.”

Weldy says she knew that she too was expected to be a “proper lady.” But “I didn’t look like my mother. And I knew I had feelings she wouldn’t have condoned. It was funny. I guess I became very inward and thoughtful about my own feelings.”

Ann Weldy as a college senior.

annbannon.comOn her graduation in 1954 from the University of Illinois, Weldy married a man 13 years older that herself. He’d been an engineer in the Middle East and he spoke French. Her degree was in French and she was, she says, “quite dazzled.”

Like most married women then, her work options were limited, so she decided to write a novel about a heterosexual university romance with a lesbian sub-plot. When she finished it, she sent it to the woman credited with launching the lesbian pulp genre, Vin Packer and her 1952 novel Spring Fire (“a story once told in whispers, now frankly, honestly written”). It was about a university romance between women and sold 1.5 million copies—more than Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel, which also came out that year.

Miraculously, Marijane Meaker, the real name of Vin Packer, wrote back to Weldy, inviting her to visit her in Manhattan. She said she’d show Weldy’s novel to her editor at Gold Medal Books.

“It felt like freedom. Like being let out of a cage!”

Weldy’s eyes shine as she recalls arriving in New York that first time. It was 1956. Meaker was in her late 20s, while she was 23. “Pete (her husband) only let me go because I’d discovered that there was a women’s hotel called the Barbizon.” Its residents over the years had included Sylvia Plath, Liza Minnelli, and Rita Hayworth.

So, wearing her Peter Pan collar and her big open smile, the ingénue set out from Philadelphia on the most exciting journey of her life. When she breezed through the doors of the Barbizon that brilliant January day in 1956, “The guy on the door said, ‘You brought the sunshine!’ So it felt like a good omen.”

And it was. The night before Meaker introduced Weldy to her editor, she took her younger guest on a trip into Wonderland—specifically Greenwich Village, the place where, according to the pulp books, all the tormented female inverts went. “Greenwich Village was pretty shabby a few years after World War II,” recalls Weldy. “But it was really incredible because you could walk around and you could afford to have fun. It felt like freedom. Like being let out of a cage!”

Meaker took her to “a nice bar, “as opposed to “a scary Mafia-type dump.” The Mafia ran most of the gay bars back then. She mentions an intriguing selection of bars that hugely outnumber the three lesbian bars that currently exist in New York City.

Weldy recalled The Provincetown Landing (on the corner of Bleecker and Thompson), The Seven Steps Down (a below-ground bar favored by a working class butch and femme crowd), The Sea Colony at Eighth Avenue opposite Abingdon Square (“A big place, a lot of tables,” says Weldy), the Page Three (a free Chinese buffet on Saturday), and the Bagatelle (“A mafia-run dump,” Weldy says while adding that it was actually her favorite lesbian bar. “There were a lot of hookups there.”)

Ann Weldy in Philadelphia in 1955, 23, as Odd Girl Out was being written.

Ann BannonFor most gay women there’s a big, soppy soft spot you keep for the first lesbian bar you went into. For me, it was the original Cubby Hole on the corner of Hudson and Morton in Greenwich Village in 1987. It was run by lesbian bar legend Elaine Romagnoli, who died in November aged 79. Stormé DeLarverie, who claimed to have started the fight that led to the Stonewall riots of 1969, was still working the door.

I remember the sight of a floor of butches and femmes dancing and a strange feeling of “home.” I was 20 and a butch called Mary ordered me a peach schnapps and it seemed to me as if that was the most sophisticated and cool drink in the whole world.

There’s a touch of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm as Weldy talks of her first lesbian bar memory. “Marijane ordered a daiquiri without sugar. They think you’re mad at the bar—pure vodka and lemon juice! I thought, ‘That’s what I should be doing too.’ I was game for anything at that point!”

The sense of giddiness in her voice is touching. And yet there was something radically different about gay bars in those pre-Stonewall days of McCarthyism, psychoanalysis to cure “inverts,” and sexism on a huge scale. Today’s worst case scenario in a lesbian bar is that you might end up going home alone. Back in the 1950s, you might end up in a prison. And not in a sexy Orange Is the New Black kind of way.

The looming Women’s House Of Detention was located at 10 Greenwich Avenue, right in the middle of the bar zone. It was built in 1932 and trumpeted as the only Art Deco prison in the world. Joan Nestle, the co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives writes in outhistory.org about the hot summer nights when she’d stand in front of the Women’s House of Detention and watch butch women shouting up to the narrow-slitted windows and of hearing from inside, “bodiless voices of love and despair.”

The prison wasn’t demolished until 1974. Subversive wit and gallows humor were survival tools of women back then. They termed the prison the “Country Club.” Although Weldy admits she was “terrified” in the bars some nights. “When you entered a bar, you always asked, ‘When was the last time you were raided?’ Because if it was recent, you hoped you were safe.”

Preceding vice squad busts, there would be a red light in the back room which would alert women that a police raid had occurred. You’d run back from the dance floor to your table and pretend you were just having drinks and discussing the weather to save yourself from arrest for the crime of dancing with a same-sex partner. This was the heyday of butches and femmes and the butches could be dragged out of the bar (and often suffer sexual violence) for not adhering to the “three article rule” meaning that if you wore more than three items of clothes associated with men, you could be arrested.

There were added complications for Black women. Audre Lorde (who mentions her “much-fingered copies of Ann Bannon’s Women in the Shadows and Odd Girl Out” in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name) writes that she also loved the Bagatelle (know as the ‘’Bag.”) She says there was a male bouncer on the door whose job was to keep out “undesirables,” but that “all too frequently, undesirable meant Black.”

Yet the bars thrived because there was nowhere else to meet people and one of Weldy’s gifts has been to record a sense of what they were like. It suddenly strikes me that maybe it’s Weldy’s humility which helped create the emotional truth in her novels which makes them timeless and has ensured her continuing relevance through the decades.

Weldy is certainly very accepting of other aspects of lesbian bars at the time which, aside from drinks for 10 cents and women bar tenders which Weldy had never seen before, includes men or “Johns” propping up the bar. “Most were harmless—they’d never do anything to hurt you.”

Being leered at by straight men in a lesbian bar is on my list of least favorite things. But Weldy points out that lesbian pulps were more commercially successful than pulps about gay men because all those titillating covers were basically marketed at these “Johns.”

“So what about the chemistry with Marijane on that first night?” I ask Weldy who, in spite of the Sapphic sub plot in her manuscript was still at this point technically a lesbian in theory only.

She hesitates and then says, “Marijane dressed in womanly way but she didn’t act femme. She was tough and pushy. I was a little scared of her frankly.”

This sounds like a definition of Ann’s type given what she’s said about her beloved Beebo Brinker character who was pretty tough and pushy too.

The twinkle suddenly reappears in Weldy’s eyes. She admits that she “hardly stayed in the women’s hotel” that first week in New York.

“Because...?”

“Yes,” she finally admits. “We did get together.”

She says that Marijane taught her, “to get over my panic about it all. But I still felt very guilty.” She adds though that, “yes, it was thrilling and scary and a whole lot of things at the same time. She was very indulgent and took it easy on me.”

Then she laughs and adds, “She taught me some nice things.”

Of course I ask what these things were but Weldy replies, very politely, that she has two children and 6 grandchildren and some of them read The Daily Beast. She does reveal, however, that it wasn’t until years later that she found out that Meaker had been, at the time, “in the midst of the early days of a two-year relationship with Patricia Highsmith. Now that’s competition!”

The great thing about the meeting was that the Meaker’s editor at Gold Medal Books, Dick Carroll, accepted Ann’s manuscript, after telling her to cut the heterosexual story and concentrate on the lesbian plot. When Marijane Meaker had published Spring Fire in 1952 the ending had involved one of the heroines being admitted to a lunatic asylum. This was because pulp books were transported by the post office and they had a right at the time to act as morality police.

But by 1957 when Ann published this first novel which became Odd Girl Out (“A confession of love as honest and as shocking as Spring Fire”—pulp authors had no say over titles, covers, or cover lines), censorship rules had relaxed a little and she was able to give her characters, and her readers, a modicum of hope.

“I had to learn everything I needed in that tiny sliver of time.”

Back in the Palm Springs house, Weldy returns to the theme of personal guilt. Clearly she feels conflicted about the way she’s lived her life.

“I think I wasn’t ready to adopt that identity. How was I to go home and be the wife that Pete knew and bear his children and have it both ways? Sneak though life without getting damaged or ostracized or rejected—all those terrible things I saw happening to other young women. I didn’t think I could stand up to that.”

And yet Weldy was brave enough to carry on writing, in spite of some serious control issues from her husband. For instance, he would only give her Philadelphia traveler’s checks—that banks in New York wouldn’t accept. He only put her on his credit card once her sizable checks started coming in.

“We were dumb as bricks,” she says of her fellow lesbian pulp writers such as Artemis Smith, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Valerie Taylor and Claire Morgan, the pen name of Patricia Highsmith who published The Price of Salt in 1953 (republished in 1990 as Carol) in a 25 cent Bantam Books lesbian pulp edition. “We didn’t know much more than our readers.”

Weldy later admits that although she only made seven or eight “field trips” up to Greenwich Village between 1956 and 1962, she made herself into a fast learner. “I had to learn everything I needed in that tiny sliver of time. While I was there I gobbled it up.”

Weldy was also driven on by the desperate letters she received from women. She was touched by “their ingenuousness, their yearning, their sense of exile” but also “their humor, their sheer guts.”

She admits that The Beebo Brinker Chronicles were a kind of DIY therapy for her. She spelled her life out on the page and some of it can’t have been easy. “Deny sex, deny who you are!” confused Laura’s gay male friend levels at her one night in I Am a Woman.

When she finished the final book of the series, Beebo Brinker, Weldy stopped writing and buried herself in academia. She admits it was a case of “seeking refuge.” She says, “I had a helicopter husband keeping an eye on my every move. I also had two growing daughters.”

Yet little did she know that the books were to “take on a life of their own.” In 1975, The New York Times reprinted some of her fiction in an academic series in its Arno Press publishing arm. Then in 1983 the women’s publishers Naiad Press did a re-print of the series complete with new covers, at which point Weldy admits she was “jet propelled out of the closet.”

Weldy feared it would cause a huge fuss and end her academic career but it turned out that, “they all knew, and nobody cared! We had quite a few gay men on the faculty, which probably helped.”

After Weldy divorced Pete in 1981, a brief period of happiness ensued. Gay women’s culture was starting to thrive and lesbians were no longer so “strange.” A cartoon strip by a then-unknown Alison Bechdel called Dykes to Watch Out For had started in 1983. There were women’s book stores, and “the whole town was blossoming in that regard. That part was lovely.”

And yes, she did meet someone. They were together for two years but, “it didn’t work. we turned out to be oil and water. We couldn’t bridge the gap.”

Ann Weldy in her office in 1990, as Associate Dean for Curriculum of the School of Arts and Sciences at Cal State University, Sacramento.

annbannon.comIn 1981 Weldy finally realized she had to divorce Pete. “He was bereft. Suicidal. He took a gun and walked to the river. We were all terrified for about two years.” In 1986, just as the divorce was finalized, she got sick with chronic fatigue. “I was a wreck for 10 years.”

Another strange twist came when one of the two children she sacrificed much of her life for converted to Catholicism and became, well, a homophobe. “She does not approve of any of this at all,” Weldy says wryly. Being Weldy, she tempers this by saying that “We get along beautifully,” but still. Her younger daughter, Inga, 62, is, in contrast, “open and welcoming and loving.” Inga, a lawyer, lives a quarter of a mile away from her mother’s house in Sacramento and has dinner with her mom twice a week.

Inga accompanied her mom to the Palm Springs dinner party. Luc is a colleague of Ann’s from Sacramento State. At one point Inga gets out her phone and shows me the Beebo Brinker actress that her mother liked the best in a 2011 production of the play in Seattle. I see a sexy, boyish person called Rhonda Soikowski. “This is the one, right mumsie?” Inga says, thrusting the phone enthusiastically before her mother. Weldy makes a slow smile.

Later that night, I ask Weldy who the love of her life was.

“Somebody I could never be with, unfortunately. It was, shall we say, a friendship from afar.”

She is currently single. “I have met several immensely attractive women, and there were one or two where the interest was mutual. But they were already partnered.” And while Weldy says that sex and desire are still “right up there,” for her, the reality is that “after a lifetime of caution, and just a few personal contacts, they are still in the realm of fantasy.”

She starts worrying again about not having been brave enough. “But I guess I can’t look back and regret the choices I made because I don’t think I had within me the wherewithal to live a bolder life. And I’m sorry about that. And yet I got things done that mattered a lot to me.”

This becomes clear the following night at the opening of the play when the audience give Weldy a tumultuous, heroine’s reception. What she got done that mattered were those eight weeks of “field trips” to New York which formed the basis of a body of work which would influence and help women around the world when there was no access to lesbian information other than in the pages of “pulp fiction.”

When the play is over, women of all ages gather excitedly around Weldy, and I’m reminded of a story she told about a woman she once met who told her that she’d reached a point of “absolute despair” about her sexuality and planned to throw herself off a bridge.

But on the day she planned to do it, she passed a book store, saw Odd Girl Out in the window, bought it, read the whole thing—and then went home for dinner.

Ann with daughters Janie, left, and Inga, right, in 2003.

annbannon.comAll the lesbians here tonight are thrilled that the legendary “Ann Bannon” is among them. They know she’s a massive piece in the jigsaw puzzle that helped them get here today. “I guess that while language and clothing and attitudes may change, human emotions are eternal,” Weldy tells one.

The younger women express their shock at all the restrictions women of Weldy’s era had to put up with. One woman in her fifties called Rose tells me she’s just moved from San Francisco to Palm Springs and she wishes it was a bit easier to meet people. “Where do we go to meet people now?” she says—a line that could have come straight out of the 1950s.

Luckily, “Ann Bannon” has become the patron saint of the lonely lesbian nearly 70 years after she first started writing. The comforting underlying message of her work is “Don’t worry, you are not alone,” and it’s a message that still needs to be disseminated.

“Women were repressed in my day and it did take some of the bounce out of life,” Weldy confides as she hugs a huge bouquet of flowers and prepares to leave the theater with Inga. “But it’s OK. We all got through it. I am basically a cheerful person.”

I ask her, finally, what she believes her legacy to be.

“Beebo Brinker!” she says, without missing a beat about the ultimate lesbian chandelier-swinger of the 1950s. “She became the personification of courage, of a better future to come. She never gave up. She could always wrap her arms around a beautiful girl and squeeze some love into her.”

Weldy becomes serious suddenly. “She saved lives after all. There can be no more wonderful reward than that for telling stories.”

The Beebo Brinker Chronicles is at the Desert Ensemble Theater in Palm Springs, Dec 17-19.